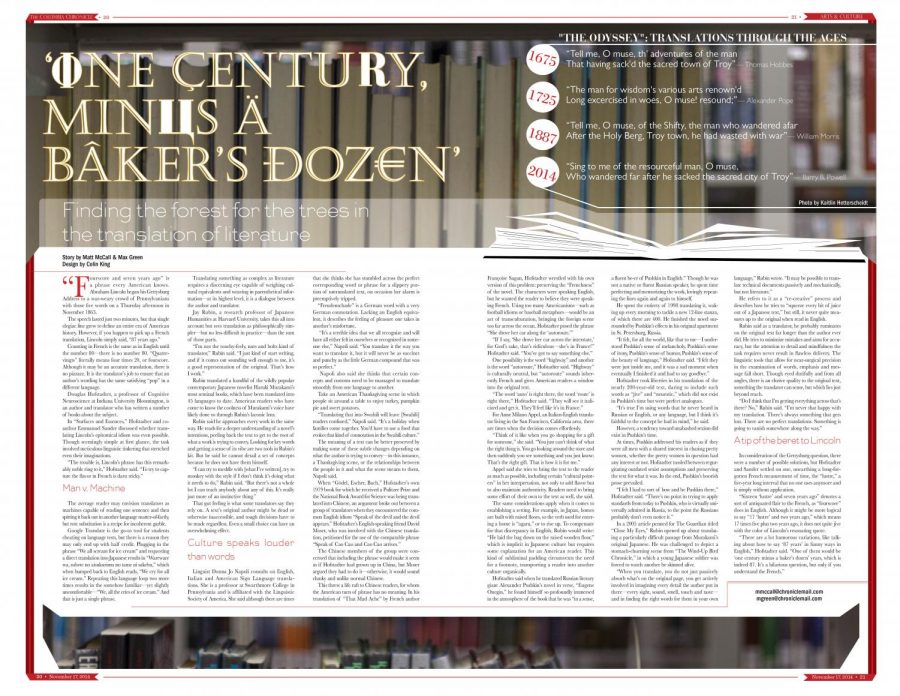

‘One century minus a baker’s dozen:’ Finding the forest for the trees in the translation of literature

‘One century minus a baker’s dozen:’ Finding the forest for the trees in the translation of literature

November 17, 2014

“Fourscore and seven years ago” is a phrase every American knows. Abraham Lincoln began his Gettysburg Address to a war-weary crowd of Pennsylvanians with those five words on a Thursday afternoon in November 1863.

The speech lasted just two minutes, but that single elegiac line grew to define an entire era of American history. However, if you happen to pick up a French translation, Lincoln simply said, “87 years ago.”

Counting in French is the same as in English until the number 80—there is no number 80. “Quatre-vingts” literally means four times 20, or fourscore. Although it may be an accurate translation, there is no pizzazz. It is the translator’s job to ensure that an author’s wording has the same satisfying “pop” in a different language.

Douglas Hofstadter, a professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at Indiana University Bloomington, is an author and translator who has written a number of books about the subject.

In “Surfaces and Essences,” Hofstadter and co-author Emmanuel Sander discussed whether translating Lincoln’s epitomical idiom was even possible. Though seemingly simple at first glance, the task involved meticulous linguistic tinkering that stretched even their imaginations.

“The trouble is, Lincoln’s phrase has this remarkably noble ring to it,” Hofstadter said. “To try to capture the flavor in French is darn tricky.”

MAN V. MACHINE

The average reader may envision translators as machines capable of reading one sentence and then spitting it back out in another language matter-of-factly, but rote substitution is a recipe for incoherent garble.

Google Translate is the go-to tool for students cheating on language tests, but there is a reason they may only end up with half credit. Plugging in the phrase “We all scream for ice cream” and requesting a direct translation into Japanese results in “Wareware wa, subete no aisukurimu no tame ni sakebu,” which when bumped back to English reads, “We cry for all ice cream.” Repeating this language loop two more times results in the somehow familiar—yet slightly uncomfortable—“We, all the cries of ice cream.” And that is just a single phrase.

Translating something as complex as literature requires a discerning eye capable of weighing cultural equivalents and weaving in parenthetical information—at its highest level, it is a dialogue between the author and translator.

Jay Rubin, a research professor of Japanese Humanities at Harvard University, takes this all into account but sees translation as philosophically simpler—but no less difficult in practice—than the sum of those parts.

“I’m not the touchy-feely, nuts and bolts kind of translator,” Rubin said. “I just kind of start writing, and if it comes out sounding well enough to me, it’s a good representation of the original. That’s how I work.”

Rubin translated a handful of the wildly popular contemporary Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami’s most seminal books, which have been translated into 45 languages to date. American readers who have come to know the coolness of Murakami’s voice have likely done so through Rubin’s laconic lens.

Rubin said he approaches every work in the same way. He reads for a deeper understanding of a novel’s intentions, peeling back the text to get to the root of what a work is trying to convey. Looking for key words and getting a sense of its vibe are two tools in Rubin’s kit. But he said he cannot detail a set of concepts because he does not have them himself.

“I can try to meddle with [what I’ve written], try to monkey with the style if I don’t think it’s doing what it needs to do,” Rubin said. “But there’s not a whole lot I can teach anybody about any of this. It’s really just more of an instinctive thing.”

That gut feeling is what some translators say they rely on. A text’s original author might be dead or otherwise inaccessible, and tough decisions have to be made regardless. Even a small choice can have an overwhelming effect.

CULTURE SPEAKS LOUDER THAN WORDS

Linguist Donna Jo Napoli consults on English, Italian and American Sign Language translations. She is a professor at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania and is affiliated with the Linguistic Society of America. She said although there are times that she thinks she has stumbled across the perfect corresponding word or phrase for a slippery portion of untranslated text, on occasion her alarm is preemptively tripped.

“Freudenschade” is a German word with a very German connotation. Lacking an English equivalent, it describes the feeling of pleasure one takes in another’s misfortune.

“It’s a terrible idea that we all recognize and will have all either felt in ourselves or recognized in someone else,” Napoli said. “You translate it the way you want to translate it, but it will never be as succinct and punchy as the little German compound that was so perfect.”

Napoli also said she thinks that certain concepts and customs need to be massaged to translate smoothly from one language to another.

Take an American Thanksgiving scene in which people sit around a table to enjoy turkey, pumpkin pie and sweet potatoes.

“Translating that into Swahili will leave [Swahili] readers confused,” Napoli said. “It’s a holiday when families come together. You’d have to use a food that evokes that kind of connotation in the Swahili culture.”

The meaning of a text can be better preserved by making some of these subtle changes depending on what the author is trying to convey—in this instance, a Thanksgiving scene, or the relationships between the people in it and what the scene means to them, Napoli said.

When “Gödel, Escher, Bach,” Hofstadter’s own 1979 book for which he received a Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award for Science was being translated into Chinese, an argument broke out between a group of translators when they encountered the common English idiom “Speak of the devil and the devil appears.” Hofstadter’s English-speaking friend David Moser, who was involved with the Chinese translation, petitioned for the use of the comparable phrase “Speak of Cao Cao and Cao Cao arrives.”

The Chinese members of the group were concerned that including the phrase would make it seem as if Hofstadter had grown up in China, but Moser argued they had to do it—otherwise, it would sound clunky and unlike normal Chinese.

This threw a life raft to Chinese readers, for whom the American turn of phrase has no meaning. In his translation of “That Mad Ache” by French author Françoise Sagan, Hofstadter wrestled with his own version of this problem: preserving the “Frenchness” of the novel. The characters were speaking English, but he wanted the reader to believe they were speaking French. Using too many Americanisms—such as football idioms or baseball metaphors—would be an act of transculturation, bringing the foreign scene too far across the ocean. Hofstadter posed the phrase “She drove her car along the ‘autoroute.’”

“If I say, ‘She drove her car across the interstate,’ for God’s sake, that’s ridiculous—she’s in France!” Hofstadter said. “You’ve got to say something else.”

One possibility is the word “highway” and another is the word “autoroute,” Hofstadter said. “Highway” is culturally neutral, but “autoroute” sounds inherently French and gives American readers a window into the original text.

“The word ‘auto’ is right there, the word ‘route’ is right there,” Hofstadter said. “They will see it italicized and get it. They’ll feel like it’s in France.”

For Anne Milano Appel, an Italian-English translator living in the San Francisco, California area, there are times when the decision comes effortlessly.

“Think of it like when you go shopping for a gift for someone,” she said. “You just can’t think of what the right thing is. You go looking around the store and then suddenly you see something and you just know: That’s the right gift. That is how it is for me.”

Appel said she tries to bring the text to the reader as much as possible, including certain “cultural pointers” in her interpretation, not only to add flavor but to also maintain authenticity. Readers need to bring some effort of their own to the text as well, she said.

The same considerations apply when it comes to establishing a setting. For example, in Japan, homes are built with raised floors, so the verb used for entering a home is “agaru,” or to rise up. To compensate for that discrepancy in English, Rubin would write: “He laid the bag down on the raised wooden floor,” which is implicit in Japanese culture but requires some explanation for an American reader. This kind of subliminal padding circumvents the need for a footnote, organically transporting a reader into another culture.

Hofstadter said when he translated Russian literary giant Alexander Pushkin’s novel in verse, “Eugene Onegin,” he found himself so profoundly immersed in the atmosphere of the book that he was “in a sense, a fluent be-er of Pushkin in English.” Though he was not a native or fluent Russian speaker, he spent time perfecting and memorizing the work, lovingly repeating the lines again and again to himself.

He spent the entirety of 1998 translating it, waking up every morning to tackle a new 12-line stanza, of which there are 400. He finished the novel surrounded by Pushkin’s effects in his original apartment in St. Petersburg, Russia.

“It felt, for all the world, like that to me—I understood Pushkin’s sense of melancholy, Pushkin’s sense of irony, Pushkin’s sense of humor, Pushkin’s sense of the beauty of language,” Hofstadter said. “I felt they were just inside me, and it was a sad moment when eventually I finished it and had to say goodbye.”

Hofstadter took liberties in his translation of the nearly 200-year-old text, daring to include such words as “jive” and “neurotic,” which did not exist in Pushkin’s time but were perfect analogues.

“It’s true I’m using words that he never heard in Russian or English, or any language, but I think it’s faithful to the concept he had in mind,” he said.

However, a tendency toward unabashed sexism did exist in Pushkin’s time.

At times, Pushkin addressed his readers as if they were all men with a shared interest in chasing pretty women, whether the pretty women in question had any interest or not. Hofstadter tussled between regurgitating outdated sexist assumptions and preserving the text for what it was. In the end, Pushkin’s boorish prose prevailed.

“I felt I had to sort of bow and be Pushkin there,” Hofstadter said. “There’s no point in trying to apply standards from today to Pushkin, who is virtually universally admired in Russia, to the point the Russians probably don’t even notice it.”

In a 2005 article penned for The Guardian titled “Close My Eyes,” Rubin opened up about translating a particularly difficult passage from Murakami’s original Japanese. He was challenged to depict a stomach-churning scene from “The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle,” in which a young Japanese soldier was forced to watch another be skinned alive.

“When you translate, you do not just passively absorb what’s on the original page, you get actively involved in imagining every detail the author put in there—every sight, sound, smell, touch and taste—and in finding the right words for them in your own language,” Rubin wrote. “It may be possible to translate technical documents passively and mechanically, but not literature.”

He refers to it as a “re-creative” process and describes how he tries to “squeeze every bit of juice out of a Japanese text,” but still, it never quite measures up to the original when read in English.

Rubin said as a translator, he probably ruminates on the original text far longer than the author ever did. He tries to minimize mistakes and aims for accuracy, but the attention to detail and mindfulness the task requires never result in flawless delivery. The linguistic tools that allow for near-surgical precision in the examination of words, emphasis and message fall short. Though eyed dutifully and from all angles, there is an elusive quality to the original text, something the translator can sense, but which lies just beyond reach.

“Do I think that I’m getting everything across that’s there? No,” Rubin said. “I’m never that happy with my translation. There’s always something that gets lost. There are no perfect translations. Something is going to vanish somewhere along the way.”

A TIP OF THE BERET TO LINCOLN

In consideration of the Gettysburg question, there were a number of possible solutions, but Hofstadter and Sander settled on one, unearthing a long-forgotten French measurement of time, the “lustre,” a five-year long interval that no one uses anymore and is simply without application.

“Sixteen ‘lustre’ and seven years ago” denotes a sort of antiquated flair to the French, as “fourscore” does in English. Although it might be more logical to say “17 ‘lustre’ and two years ago,” which means 17 times five plus two years ago, it does not quite jive with the color of Lincoln’s resonating quote.

“There are a lot humorous variations, like talking about how to say ‘87 years’ in funny ways in English,” Hofstadter said. “One of them would be ‘one century minus a baker’s dozen’ years, which is indeed 87. It’s a hilarious question, but only if you understand the French.”