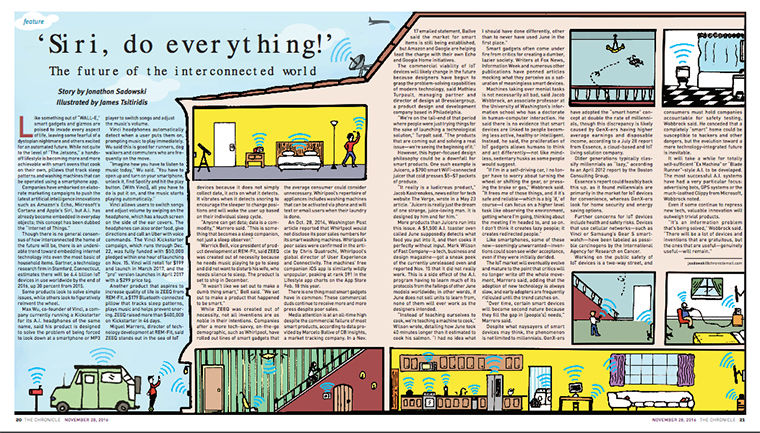

‘Siri, do everything!’ The future of the interconnected world

‘Siri, do everything!’ The future of the interconnected world

November 28, 2016

Like something out of “WALL-E,” smart gadgets and gizmos are poised to invade every aspect of life, leaving some fearful of a dystopian nightmare and others excited for an automated future. While not quite to the level of “The Jetsons,” a hands-off lifestyle is becoming more and more achievable with smart ovens that cook on their own, pillows that track sleep patterns and washing machines that can be operated using a smartphone app.

Companies have embarked on elaborate marketing campaigns to push the latest artificial intelligence innovations such as Amazon’s Echo, Microsoft’s Cortana and Apple’s Siri, but A.I. has already become embedded in everyday objects; this concept has been dubbed the “Internet of Things.”

Though there is no general consensus of how interconnected the home of the future will be, there is an undeniable trend toward embedding internet technology into even the most basic of household items. Gartner, a technology research firm in Stamford, Connecticut, estimates there will be 6.4 billion IoT devices in use worldwide by the end of 2016, up 30 percent from 2015.

Some products look to solve simple issues, while others look to figuratively reinvent the wheel.

Max Wu, co-founder of Vinci, a company currently running a Kickstarter for its A.I. headphones of the same name, said his product is designed to solve the problem of being forced to look down at a smartphone or MP3 player to switch songs and adjust the music’s volume.

Vinci headphones automatically detect when a user puts them on, prompting music to play immediately. Wu said this is good for runners, dog walkers and commuters who are frequently on the move.

“Imagine how you have to listen to music today,” Wu said. “You have to open up and turn on your smartphone, unlock it, find Spotify and hit the play button. [With Vinci], all you have to do is put it on, and the music starts playing automatically.”

Vinci allows users to switch songs and adjust volume by swiping on the headphone, which has a touch screen on the side of the ear covers. The headphones can also order food, give directions and call an Uber with voice commands. The Vinci Kickstarter campaign, which runs through Dec. 22, was fully funded with $50,000 pledged within one hour of launching on Nov. 15. Vinci will retail for $199 and launch in March 2017, and the “pro” version launches in April 2017 with a $299 price tag.

Another product that aspires to increase quality of life is ZEEQ from REM-Fit, a $179 Bluetooth-connected pillow that tracks sleep patterns, plays music and helps prevent snoring. ZEEQ raised more than $400,000 on Kickstarter in 46 days.

Miguel Marrero, director of technology development at REM-Fit, said ZEEQ stands out in the sea of IoT devices because it does not simply collect data, it acts on what it detects. It vibrates when it detects snoring to encourage the sleeper to change positions and will wake the user up based on their individual sleep cycle.

“Anyone can get data; data is a commodity,” Marrero said. “This is something that becomes a sleep companion, not just a sleep observer.”

Warrick Bell, vice president of product development at REM-Fit, said ZEEQ was created out of necessity because he needs music playing to go to sleep and did not want to disturb his wife, who needs silence to sleep. The product is set to ship in December.

“It wasn’t like we set out to make a dumb thing smart,” Bell said. “We set out to make a product that happened to be smart.”

While ZEEQ was created out of necessity, not all inventions are as noble in their intentions. Companies after a more tech-savvy, on-the-go demographic, such as Whirlpool, have rolled out lines of smart gadgets that the average consumer could consider unnecessary. Whirlpool’s repertoire of appliances includes washing machines that can be activated via phone and will text or email users when their laundry is done.

An Oct. 28, 2014, Washington Post article reported that Whirlpool would not disclose its poor sales numbers for its smart washing machines. Whirlpool’s poor sales were confirmed in the article by Chris Quatrochi, Whirlpool’s global director of User Experience and Connectivity. The machines’ free companion iOS app is similarly wildly unpopular, peaking at rank 591 in the Lifestyle app charts on the App Store Feb. 18 this year.

There is one thing most smart gadgets have in common: These commercial duds continue to receive more and more press despite poor sales.

Media attention is at an all-time high despite the commercial failure of most smart products, according to data provided by Marcelo Ballve of CB Insights, a market tracking company. In a Nov. 17 emailed statement, Ballve said the market for smart items is still being established, but Amazon and Google are helping lead the charge with their own Echo and Google Home initiatives.

The commercial viability of IoT devices will likely change in the future because designers have begun to grasp the problem-solving capabilities of modern technology, said Mathieu Turpault, managing partner and director of design at Bresslergroup, a product design and development company based in Philadelphia.

“We’re on the tail-end of that period where people were just trying things for the sake of launching a technological solution,” Turpalt said. “The products that are coming out and solving a real issue—we’re seeing the beginning of it.”

However, this hyper-focused design philosophy could be a downfall for smart products. One such example is Juicero, a $700 smart WiFi-connected juicer that cold presses $5–$7 packets of produce.

“It really is a ludicrous product,” Jacob Kastrenakes, news editor for tech website The Verge, wrote in a May 23 article. “Juicero is really just the dream of one strange, juice-loving man. It is designed by him and for him.”

More products than Juicero run into this issue. A $1,500 A.I. toaster oven called June supposedly detects what food you put into it, and then cooks it perfectly without input. Mark Wilson of Fast Company—a tech, business and design magazine—got a sneak peek of the currently unreleased oven and reported Nov. 15 that it did not really work. This is a side effect of the A.I. program having to learn much of its protocols from the failings of other June models worldwide; in other words, if June does not sell units to learn from, none of them will ever work as the designers intended.

“Instead of teaching ourselves to cook, we’re teaching a machine to cook,” Wilson wrote, detailing how June took 40 minutes longer than it estimated to cook his salmon. “I had no idea what I should have done differently, other than to never have used June in the first place.”

Smart gadgets often come under fire from critics for creating a dumber, lazier society. Writers at Fox News, Information Week and numerous other publications have penned articles mocking what they perceive as a saturation of meaningless smart devices.

Machines taking over menial tasks is not necessarily all bad, said Jacob Wobbrock, an associate professor at the University of Washington’s information school who has a doctorate in human-computer interaction. He said there is no evidence that smart devices are linked to people becoming less active, healthy or intelligent. Instead, he said, the proliferation of IoT gadgets allows humans to think and act differently—not like mindless, sedentary husks as some people would suggest.

“If I’m in a self-driving car, I no longer have to worry about turning the wheel or shifting the gear, or pressing the brake or gas,” Wobbrock said. “It frees me of those things, and if it’s safe and reliable—which is a big ‘if,’ of course—I can focus on a higher level task like observing the environment, getting where I’m going, thinking about the meeting I’m headed to, and so on. I don’t think it creates lazy people; it creates redirected people.”

Like smartphones, some of these new—seemingly unwarranted—inventions could soon see wider acceptance, even if they were initially derided.

The IoT market will eventually evolve and mature to the point that critics will no longer write off the whole movement, Marrero said, adding that the adoption of new technology is always slow, and early adopters are frequently ridiculed until the trend catches on.

“Over time, certain smart devices will become second nature because they fill the gap in [people’s] needs,” Marrero said.

Despite what naysayers of smart devices may think, the phenomenon is not limited to millennials. GenX-ers have adopted the “smart home” concept at double the rate of millennials, though this discrepancy is likely caused by GenX-ers having higher average earnings and disposable income, according to a July 28 report from Essence, a cloud-based and IoT living solution company.

Older generations typically classify millennials as “lazy,” according to an April 2012 report by the Boston Consulting Group.

Essence’s report could feasibly back this up, as it found millennials are primarily in the market for IoT devices for convenience, whereas GenX-ers look for home security and energy saving options.

Further concerns for IoT devices include health and safety risks. Devices that use cellular networks—such as Vinci or Samsung’s Gear S smartwatch—have been labeled as possible carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

Working on the public safety of IoT devices is a two-way street, and consumers must hold companies accountable for safety testing, Wobbrock said. He conceded that a completely “smart” home could be susceptible to hackers and other dangers, but the evolution toward a more technology-integrated future is inevitable.

It will take a while for totally self-sufficient “Ex Machina” or “Blade Runner”-style A.I. to be developed. The most successful A.I. systems have had a very particular focus: advertising bots, GPS systems or the much-loathed Clippy from Microsoft, Wobbrock noted.

Even if some continue to repress new tech, valuable innovation will outweigh trivial products.

“It’s an information problem that’s being solved,” Wobbrock said. “There will be a lot of devices and inventions that are gratuitous, but the ones that are useful—genuinely useful—will remain.”