Amidst the part-time faculty union strike, now nearly two-weeks old, the Chronicle compiled all of the available information about the college’s financial situation since administrators started talking openly about the deficit last April. But even before that, there were warning signs.

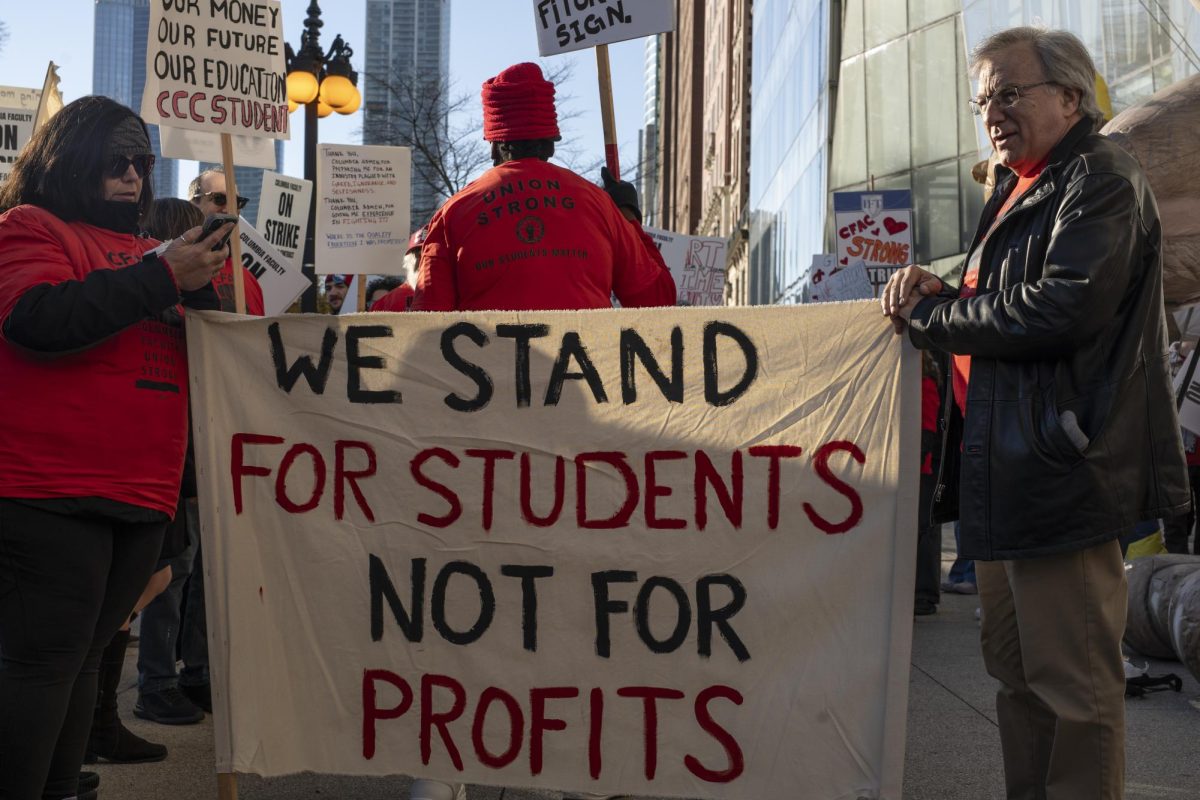

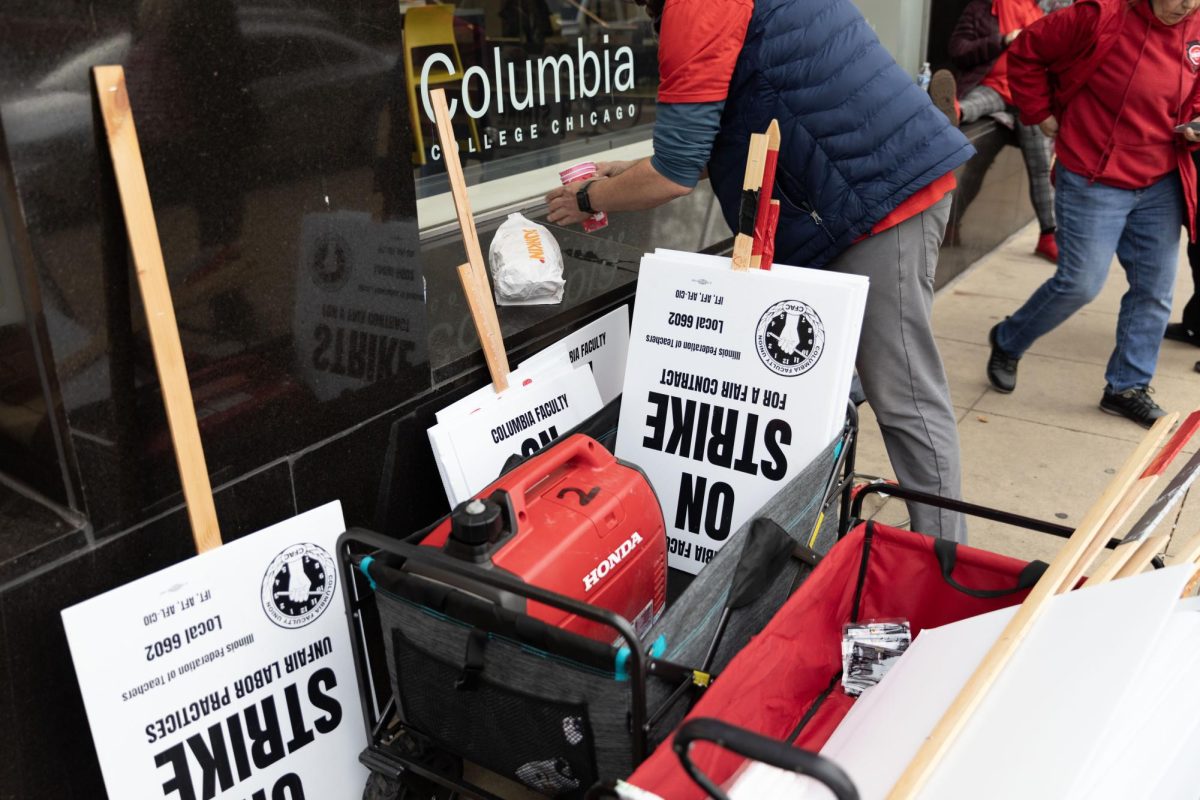

The college is now implementing a series of cost-cutting measures to close a $20 million deficit. Some of these cuts – primarily around course offerings – are at the center of a strike by the Columbia Faculty Union that started Oct. 30. The college also is considering plans to sell some buildings, eliminate graduate programs with low enrollment and reduce the number of core credits required to graduate.

The college has said these measures are necessary to meet a directive by the Board of Trustees to close the deficit by 2026. The union has primarily blamed the shortfall on excessive spending on administration salaries and bonuses.

So how did the college end up with a deficit in the first place?

For the past several years, the college’s spending has been more than its revenue, which is what led to the deficit. Any spending decisions are obviously part of that – and a source of dispute with the union. But for this, we are going to focus on the budget gap itself.

The college undertook planned deficit spending – what organizations and even governments do – in an attempt to “jumpstart” enrollment and get revenue back up. Its strategy was to offer more scholarships and discounted tuition rates to increase enrollment, necessary to bring it tuition revenue. But it didn’t work, in part, because of the extra costs associated with the pandemic and because those enrollment targets weren’t met.

This year the college will add $20 million in deficit spending to the $80 million spent since 2019, for a total of $100 million in accumulated deficit spending. This is depleting the cash reserves.

Types of revenue: The college essentially has three avenues to meet operating expenses. They include the endowment, tuition revenue and cash reserves.

The majority of Columbia’s revenue comes from student’s tuition dollars. Many large-scale universities have medical centers, research grants and sports programs to also bring in revenue to the college. Columbia does not.

Columbia’s income covers about 90 cents of every dollar in costs, resulting in the college dipping into the reserves for the remainder.

Cash reserves are projected to be depleted by the end of fiscal year 2024-2025.

A separate endowment currently has about $190 million in it, and would decrease to $90 million in the next five years, if no corrective actions are taken.

A college endowment is a pool of funds that colleges use to achieve short and long-term goals to provide a financial cushion.

The endowment is not part of the annual budget, and its use is generally restricted. While some returns on the investment can be tapped, the endowment is not something the college – or most colleges and universities – can dip into whenever there is deficit.

For context: In fiscal year 2020, Columbia made less in total revenue than it paid in expenses, becoming the first of at least four anticipated, consecutive years the college will operate with a budget deficit.

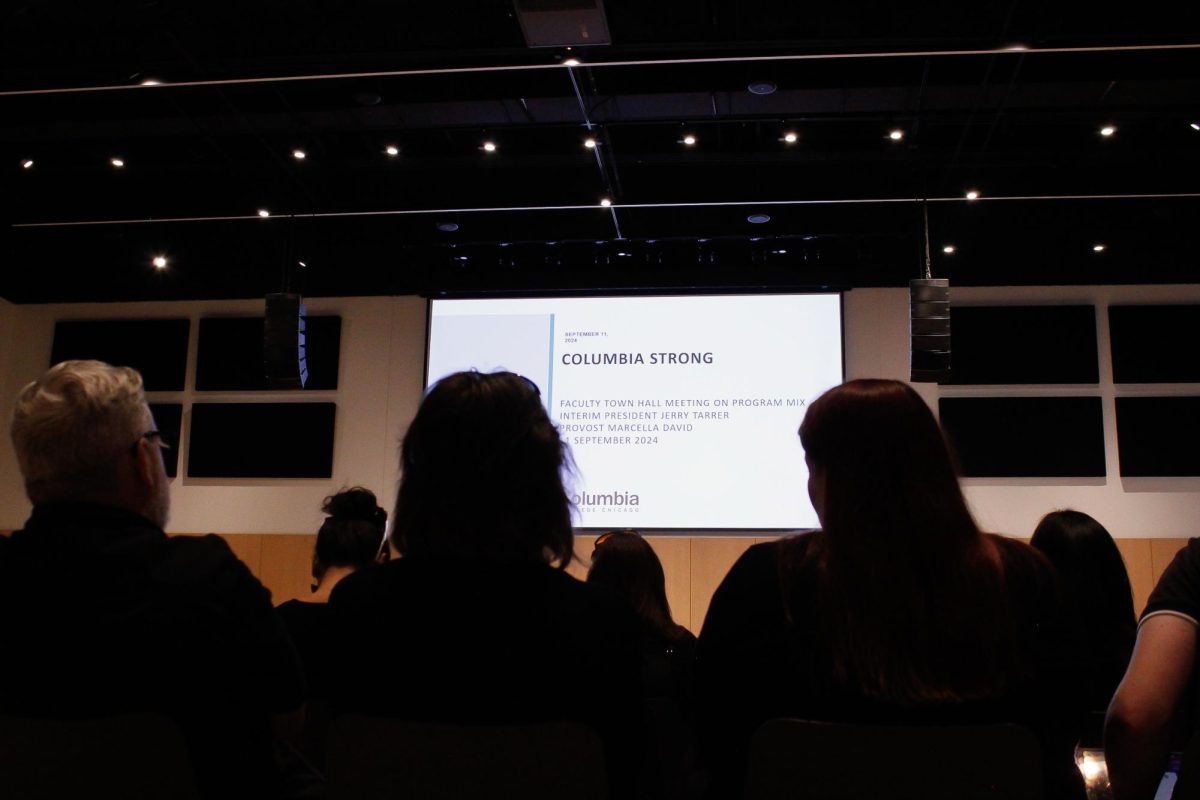

In June 2021, Columbia’s CFO, Jerry Tarrer, told the Chronicle that some of the deficit was planned, specifically about $11 million, but the goal was to close the deficit by increasing enrollment and resources.

But COVID-19 continued to cause problems.

“Before the pandemic, the college was entering several years of planned deficits of about $10 million a year to fund investments in our enrollment strategy. COVID slowed the progress we were making on enrollment and brought lots of unexpected expenses, and deficits have been in the $25 million range instead,” Lukidis told the Chronicle in June 2022.

By September 2023, President and CEO, Kwang-Wu Kim, acknowledged the efforts had fallen short because the college had not been able to retain enough students or attract new ones.

In comparison: Many colleges and universities are facing similar challenges from declining enrollment and economic pressures stemming from the pandemic.

Some of their deficits are huge compared to Columbia. The California State University system has a $1.5 billion deficit. Nearby, DePaul University has a $56 million deficit.

Since 2016, eight colleges in Illinois have closed or are planning to close because of financial difficulties.

What students are saying: Brianna Cooper, a sophomore audio arts major, said she doesn’t think the college has been transparent about the deficit.

“I wasn’t aware that the school had a deficit before I applied here. I knew nothing about that until this year,” Cooper said. “I wish I knew that information.”

The college has raised tuition to help cover the deficit.

“The increase in tuition and housing makes me feel like ‘What am I doing here if they keep raising the price?” said Amber Cortecero, a junior music business major. “Why should I be motivated for class if I won’t be able to live and attend here next year?’”