One year ago today marked the start of Columbia’s historic part-time faculty union strike, which lasted seven weeks and was the longest adjunct faculty strike in U.S. history before it ended Dec. 17.

In the year since, the college has undergone sweeping administrative restructuring and budget cuts. Over the summer, the college laid off 70 staff members, including four therapists in the Counseling Center, four librarians, two academic advisors and nine staff in the tutoring center. Six people who worked in student financial aid also lost their jobs. In August, the college closed the on-campus health center. The college now plans to eliminate 18 of its 58 majors.

Enrollment is also down this fall by 1,000 students, which interim President and CEO Jerry Tarrer has attributed, in part, to bad press from the strike.

College leaders, including the chair of the Board of Trustees, have blamed the strike for the current financial crisis. The deficit, now at $17 million, bloomed to $38 after the strike. But the college’s financial troubles started well before the strike.

This is how it unfolded.

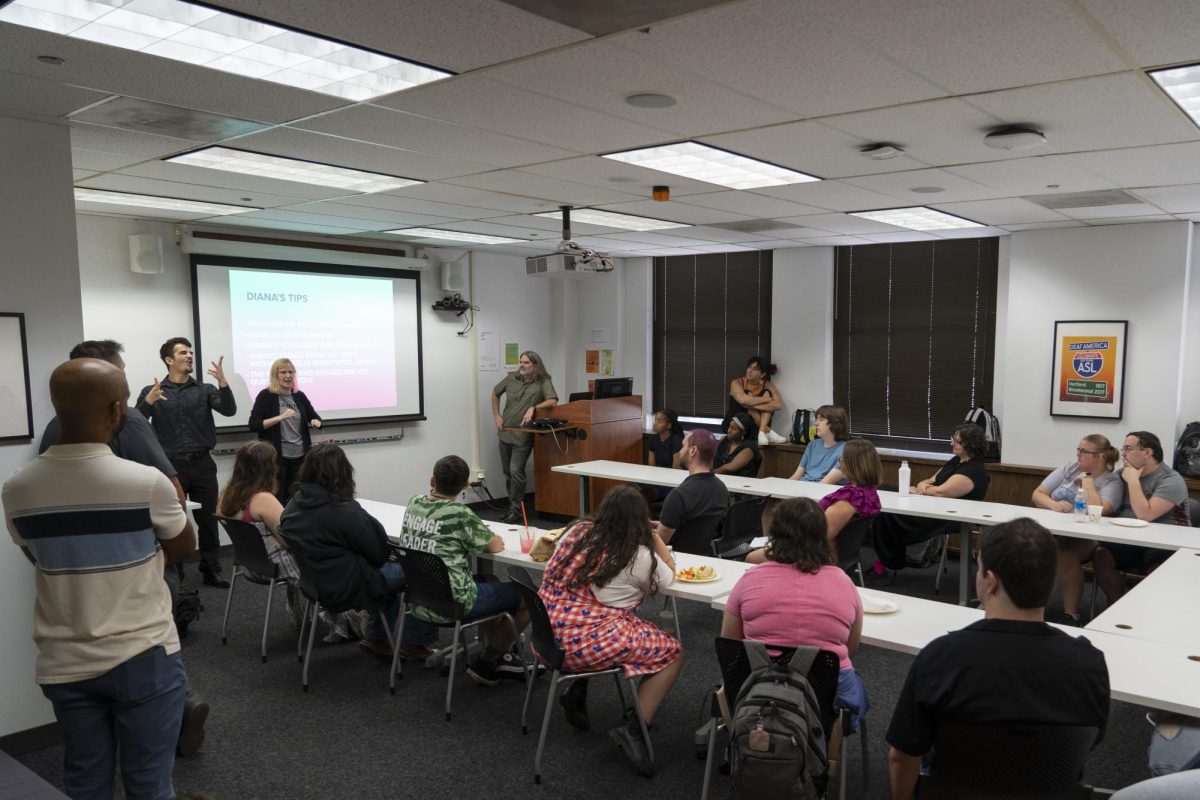

The first real hint of the looming dispute came when the Columbia Faculty Union hosted a town hall on Oct. 20, 2023, to protest a series of cost-cutting measures the college was attempting to make to cut down a financial deficit of about $20 million at that time.

Hundreds of students attended the town hall after seeing flyers promoting the event as “the real town hall.” Diana Vallera, a part-time instructor in the School of Visual Arts and CFAC president, accused the college of giving administrators bonuses to people who are “already grossly overpaid.”

The union began voting whether to authorize a strike that same day.

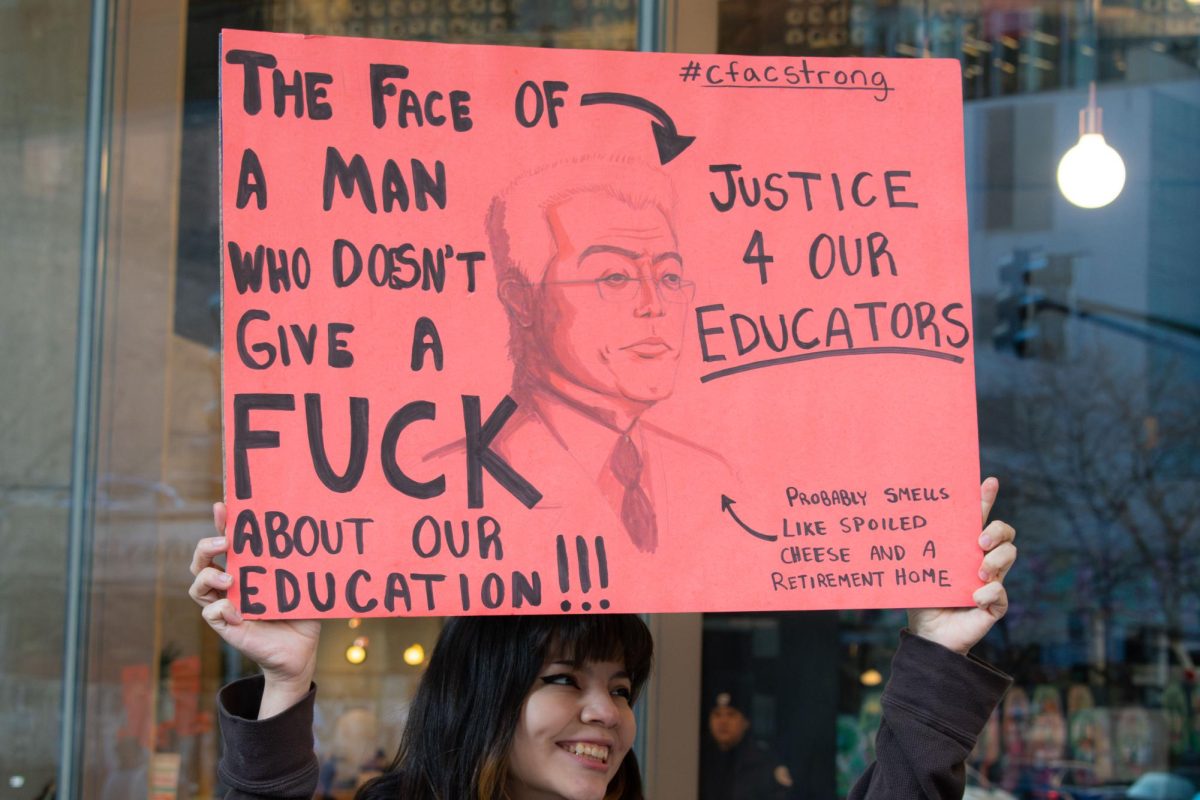

The following morning, on Oct. 21, 2023, a Saturday, former President and CEO Kwang-Wu Kim held a president’s brunch for Family Weekend on the 5th floor of the Student Center. Led by Vallera, hundreds of students interrupted the event to confront Kim and demand that he step down amid the previous growing concerns over cost-cutting measures, including closing courses and increasing class sizes.

After initially agreeing to talk for this story, Vallera did not reply to a second email request by the time of publication.

Early in the morning on Thursday, Oct. 26, the union announced its 88% approval among union members voting to authorize the strike.

On Oct. 30, the first day of the strike, faculty and students marched along 600 S. Michigan Ave.

A Chronicle analysis at the time found that well over the majority of classes at least on the first day of the strike were taught by part-time instructors. The disruption was felt widely as the strike dragged on. In the fall of 2023, the college had 221 full-time faculty and more than twice as many part-time instructors.

Three weeks into the strike, with classes not meeting, parents created a Facebook page to share updates on the strike and held a Zoom meeting with administrators to share their growing frustrations.

Just before Thanksgiving, Senior Vice President and Provost Marcella David shared in an email that the college would begin asking full-time faculty to step in to help students complete courses that part-time faculty had stopped teaching.

By then, even though the union had threatened part-time faculty who crossed the picket line with disciplinary action, nearly half of the 584 part-time faculty were back in their classrooms.

On Dec. 1, both the union and college agreed to bring in a federal mediator, which happens when the parties don’t believe they’ll reach an agreement in direct negotiations.

Just days after the fall semester ended, the college reached a tentative deal with the part-time faculty union, ending the strike with a new contract that gave instructors new titles, a 16% pay increase over four years, signing bonuses, money for course cancellations and a new system to pay part-time instructors for larger class sizes.

Although the union initially had rallied students over a demand to freeze tuition, which is not something they can bargain over, tuition increased 5% this fall for the second year in a row. Fees also went up by 2.1%, and housing increased 3%.

The college did offer a $500 tuition credit to students who had a class where a part-time instructor was on strike. Anyone who graduated in December received a $500 refund per class. Students with multiple classes where the part-time instructor was out on strike got the credit for each class.

But for some students, the instruction time they missed during the strike was the bigger loss.

Sophomore illustration major Harriet Moxon assumed the strike was only going to last a couple of weeks. Their “Intro to Visual Culture” didn’t meet because the instructor was on strike.

“It was just never the same after that,” Moxon said.

But Moxon was sympathetic towards peers who had it worse.

“I just felt really sorry for my fellow classmates who had to leave and go to a different school. It was very stressful for them,” Moxon said. “Although I was very fortunate that I didn’t have to go through that, I definitely think it affected me somewhat.”

Kevin Galan, a senior film and television major, only had one full-time faculty member last fall, meaning that they only had one out of five classes throughout the seven weeks.

Galan said that they assumed the strike would last all semester.

For Sergio Martinez, a first-year acting major, he decided to come to Columbia despite the strike.

“They were still having many art classes, and I thought it would be a good idea for me to go,” Martinez said. “I don’t know much about the strike. But they were fighting for a good cause.”

Junior Christos Sirigas, an advertising and acting double major, transferred to the college last spring, just after the strike ended.

He said he didn’t know about the strike when he was transferring from his previous institution and instead found out about it after having conversations with classmates and peers once he got on campus.

“There always will be a concern, but I consider myself kind of lucky because a lot of students kind of struggle with all that,” Sirigas said. “They struggled with it because they’re taking a bunch of degrees away and then sending classes away. So I consider myself more lucky than concerned because the students, they’ve been through a lot more than me.”

Copy edited by Vanessa Orozco and Manuel Nocera