Tax forms reveal college’s finances in early days of the pandemic; administrators discuss plans to right the ship

June 3, 2022

For the first time since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, a federal tax form has offered insight into how the pandemic disrupted the college’s financial plans during fiscal year 2020 — covering September 1, 2019-August 31, 2020 — paving the way for losses in revenue, a raft of unexpected expenses and deficits that are likely to linger for some time.

The 990 tax form is a federal tax document for nonprofit institutions, which shows the financial health of the school. In addition to listing top administrative salaries, the form also shows revenue and expenses related to Residence Life services and a comparison of the school’s overall revenue and expenses. The form also documents results of the college’s fundraising efforts, financial aid awarded to students and more.

The tax form paints a bleak picture of the college’s financial state, which has grown worse over the two years that followed, and charts the beginning of a period of overall budget deficits — exacerbated by the pandemic — that administrators say will continue through at least the next year.

While the most recent 990 tax form offers only a snapshot of the beginning of turbulent times — including the first six months of the pandemic — it’s a precursor of tough times to come, including a 10% tuition increase starting in Fall 2022. And the financial picture seen in the form cast a shadow over other developments of the past year, including the settling of labor contracts with two Columbia unions and awarding bonuses to non-union faculty and staff.

After examining the form from fiscal year 2020 and speaking to administrators and other campus leaders, the Chronicle broke it down into three parts: administrative salaries, revenue and expenses and fundraising efforts. The numbers shown in fiscal year 2020’s form were largely impacted by the second half of the school year, which is when COVID-19 shut down Columbia’s physical campus while terms such as “hybrid” and “Zoom” became part of the new college vernacular.

Administration Salaries

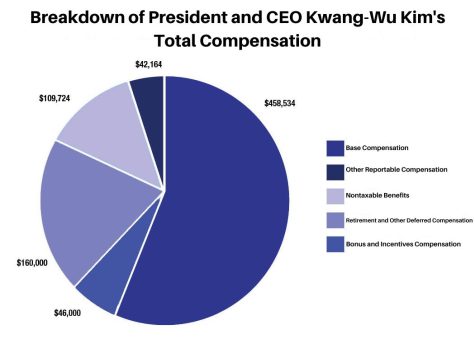

Based on the college’s annual 990 tax form, President and CEO Kwang-Wu Kim received $816,422 in total compensation and benefits for the 2020 fiscal year, an increase of $28,531 from the $787,891 reported for Kim in fiscal year 2019. His total reportable compensation for FY20 was $546,698, which includes his base salary plus a bonus and “other reportable compensation.”

While the 990 form shows an increase in Kim’s salary during fiscal year 2020, Jerry Tarrer, senior vice president of Business Affairs and CFO, said that in the following tax year Kim took a 10% pay cut and members of his cabinet took a 5% decrease in their salaries in the period from September 2020 through early spring of 2021, a measure taken due to COVID-19.

For the 15 highest-paid employees at Columbia, their total compensation amounts are broken down into five categories: base compensation or take-home salary, bonus and incentive compensation, “other reportable compensation,” retirement compensation and nontaxable benefits, which are calculated together on the form as the total compensation for the given year.

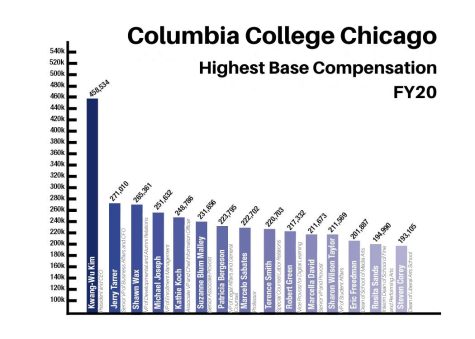

In fiscal year 2020, Kim’s base compensation was reported as $458,534, doubling most of the other salaries in the President’s Cabinet and that of other Columbia officials.

Diana Vallera, president of Columbia’s part-time faculty union — or CFAC — and an adjunct faculty member in the Photography Department, described the President’s Cabinet compensation as “egregious” and “unethical.”

She said CFAC is already making plans to meet with faculty, staff and students to discuss what is reflected in the 990 form and to seek additional information from Tarrer and Kim.

Vallera said she is concerned for the college’s future and does not think it will be able to sustain itself if current financial strategies remain the same.

“I don’t think Dr. Kim clearly cares, in my opinion, if the college is going to be successful or not. He’s made all the money he needs to make; he can leave. He’s done, as are some of these other high-paid salaries,” Vallera said. She said the faculty and staff are all exhausted because “they have us doing all this extra work; we’re not getting paid for it; we can’t make ends meet.”

Vallera said what stood out to her most is the highest compensated individuals are not instructors in the classrooms. She said the faculty who work directly with students have not received a raise in years and part-time faculty do not have health benefits.

In an email to the Chronicle on June 1, Lukidis said some full-time faculty received performance-based increases in 2019, with promotional increases granted to faculty each year. Lukidis added that Columbia announced “across the board” increases for full-time faculty on May 26 in an email from the Office of the President. The increases will be effective starting in August.

Tarrer said Kim’s salary, as has been the case with past Columbia presidents, is decided by the Board of Trustees, a group of 21 individuals who are elected to oversee management decisions on behalf of the college. The 990 form from fiscal year 2020 does not indicate that members of the Board of Trustees received any compensation from the college.

Tarrer said as the president of the college, Kim has a contract with the Board of Trustees that no other Columbia faculty, staff or official has, which sets agreed upon annual bonuses.

Tarrer said this type of pre-negotiated contract is not atypical when it comes to college presidents and CEOs who are managed by a board of trustees, especially for private institutions, as public colleges and universities often have different arrangements in place for their presidents.

A three-way comparison of comparable institutions between Columbia, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Emerson College found that Kim’s reportable compensation of nearly $547,000 was slightly behind that of presidents at the two other schools. Emerson’s president, M. Lee Belton, earned just over $754,000, while Elissa Tenny of SAIC earned nearly $687,000.

When other benefits such as the use of the president’s mansion, health coverage and other contract extras are factored in, Kim’s total compensation of $816,422 puts him in second place behind Belton’s total compensation of $909,742. Tenny’s total compensation earned was $730,453, according to her school’s tax form.

Revenue and Expenses

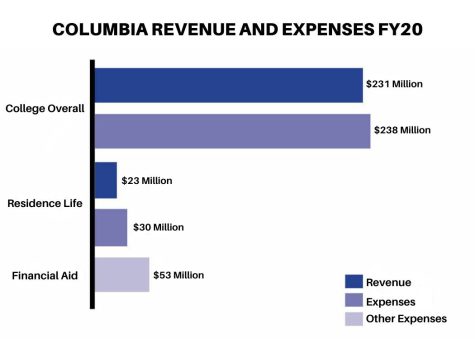

In fiscal year 2020, Columbia made less in total revenue than it paid in expenses, becoming the first of at least four anticipated, consecutive years the college will operate with a budget deficit. The 990 tax form reports a total of approximately $231 million in overall revenue and $238 million in expenses for fiscal year 2020, with a financial deficit of approximately $6.8 million.

But, in fiscal year 2021, a tax year for which documentation has not yet been released, the operating deficit made a drastic jump to $25.5 million, according to Tarrer.

Tarrer said some of this deficit was planned, specifically about $11 million, but the goal was to close the deficit by increasing enrollment and resources.

“Now, of course, the pandemic brought another wrinkle, made our lives a bit more challenging and made the deficits deeper than we had originally planned,” Tarrer said.

Lambrini Lukidis, associate vice president of Strategic Communications and External Relations, said the budget deficit for fiscal years 2022 and 2021 are about the same at $25.1 million, though the deficit for fiscal year 2023 is forecast to be less than that, but she said these numbers are dependent on enrollment.

According to Tarrer, the majority of college revenue, about 60% to 70%, goes toward salaries and the rest toward building operations, supplies and equipment, including the college’s technology infrastructure, and other costs like advertising and insurance.

The college spent $52.8 million on financial aid to students in fiscal year 2020, which is approximately $14 million more than what the college gave in financial aid to students the prior year. Tarrer said grants and scholarships are considered an expense, and due to the college significantly increasing financial aid in Fall 2019, less tuition money came in. The college is financially reliant on tuition dollars, with it making up 85% of the school’s revenue, as reported by the Chronicle.

In an email to the Chronicle on April 29, Lukidis said the college is on “solid financial footing,” as confirmed by a credit rating agency.

“Before the pandemic, the college was entering several years of planned deficits of about $10 million a year to fund investments in our enrollment strategy. COVID slowed the progress we were making on enrollment and brought lots of unexpected expenses, and deficits have been in the $25 million range instead,” Lukidis said in the email.

Keith Kostecka, associate professor in the Science and Mathematics Department and the chair of the financial affairs committee of the Faculty Senate, said the school’s deficit worries him.

“It does worry me because you don’t want to be in the red to begin with,” Kostecka said. “From some information that has been relayed to [the Faculty Senate] over the course of this past year by [Tarrer], specifically, is that there is a trend, and the trend is that expenses and revenue are not meeting.”

Kostecka said the school did try to address the disparity between revenue and expenses in part by the 10% tuition increase, but there is still more the school will have to do in years to come to accomplish zeroing out the deficit.

In a follow-up email to the Chronicle on May 5, Tarrer said he had no further comments regarding Kostecka’s statements.

Craig Sigele, academic manager in the Communication Department and president of the United Staff of Columbia College, said the deficit is manageable.

“It is hard work running an educational facility and, I mean, yeah, debt is not good … [but] it sounds like manageable debt,” Sigele said. “I think this school has been fiscally responsible.”

Sigele said he trusts the president and the Board of Trustees to look at all aspects of Columbia’s financial health prior to making decisions.

Tarrer said during fiscal year 2020, Columbia administered a 2% tuition increase. When asked in an interview about the upcoming 10% tuition increase for the 2022-2023 academic year, Tarrer said the increase will lead to additional revenue at the college, and the money will flow throughout operations for the institution.

Tarrer said in 2022 the college received $8.4 million in Higher Education Emergency Relief Funds, or HEERF funds, related to COVID-19, which he considered a “significant help,” but next year Columbia and colleges across the country are not expecting this aid.

Lukidis said next semester’s tuition increase was not implemented to offset HEERF funds, but according to Tarrer’s predictions, the 10% tuition increase will generate an additional $9 to $10 million in revenue — just a little more than the HEERF funds received last year. Some of this will be used to fund an increase in grants and financial aid provided to students.

Tarrer said with the additional revenue from the tuition increase, Columbia is still expecting an operating deficit in the millions.

“Despite the fact that we have a tuition increase, there’s not a whole lot of additional revenue coming into the institution,” Tarrer said.

As for Residence Life services during fiscal year 2020, the college lost a significant $6.4 million in revenue as a result of the refunds issued to hundreds of students who were forced to pack up and move out of the residence halls at the start of the pandemic.

Tarrer said these are not normal numbers for the college’s Residence Life services, and he attributed it to the pandemic.

“The college is still accountable for paying the lease payments, regardless of whether there are students living in the dorms or not,” Tarrer said. “We were still accountable for meeting all expenses associated with money in the dorms. But there was a drop in revenue because when we closed the dorms, we refunded students their funds.”

In looking at the bigger picture, Tarrer said this 990 form is about the overall trends at the institution since it reflects numbers from two years ago.

“The biggest trend is we’re doing everything in our power to try to allocate our resources in a wise way so that we can make sure that the students who enroll in our institution and the families who spend their money for the students to come here are getting the best possible experience,” Tarrer said.

Tarrer said the current challenge for the college and the country is inflation, but this requires the institution to mindfully allocate resources.

Lukidis said some of the college’s financial challenges stem from low student retention, which was prevalent before COVID-19.

“The college has the resources to navigate through this financial turbulence and has plans to return to balanced budgets over the next few years through healthier enrollment and increased tuition revenue,” Lukidis said.

Donations and Fundraising

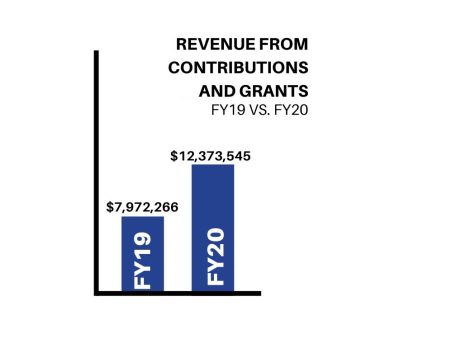

During fiscal year 2020, the school saw an increase of $4.4 million in gifts, grants, contributions and membership fees to the college compared to fiscal year 2019.

Shawn Wax, vice president for Development and Alumni Relations at Columbia, said the increase in gifts between 2019 and 2020 can be attributed to years of relationship building with donors in fundraising efforts.

Kostecka said he has been employed at Columbia since 1989, and to his knowledge, there has not been a major donor to the school. He said a major donation would be a seven-figure dollar amount.

“We have been told that there are large donations that are in the works for that matter, but we’ve never seen anything happen,” Kostecka said. “I understand that when a new president comes along it takes a while to develop relationships. … President Kim was hired to help with fundraising, and to this point, we have not seen any large donations.”

In an email to the Chronicle on May 5, Wax said he has ongoing meetings with many campus leaders to provide updates on fundraising and alumni relations work.

“I’m disappointed to learn that [Kostecka] has no knowledge of any major gift donors to the college,” Wax said. “I have ongoing meetings with quite a few campus leaders including deans, department chairs, my colleagues on the cabinet as well as members of the Board of Trustees to provide updates on our fundraising and alumni relations work.”

In his email, Wax said he feels fortunate that Columbia’s campus community invests time and energy into fundraising efforts. Wax added that he thinks the college as a whole can do a better job of celebrating Columbia’s fundraising “wins,” both big and small.

In Fall 2021, Wax said Development and Alumni Relations launched the Alumni Network with more than 1,000 alumni joining and more than 300 making donations to Columbia.

“We are on pace to exceed a 20-year record for alumni giving, a strong indication that our strategies are working,” Wax said.

In an email to the Chronicle also on May 5, Lukidis said since the restructuring of Columbia’s fundraising efforts four years ago, the college has raised nearly $28 million, which is a 75% increase over the $16 million Columbia accumulated the four years prior.

Lukidis said this increase occurred “even with the negative impact of COVID.”

Lukidis added that the largest gift since 2017, when Wax took over as vice president of Development and Alumni Relations, was a donation of $7 million, which was in support of renovating the Museum of Contemporary Photography. She said since 2017 the college also received the largest gift from a trustee, $2 million, and the largest gift from an alum, totaling $1 million to support the construction of the Student Center. When asked to identify the donors, Columbia declined.

On May 16 in an email to the Chronicle, Lukidis declined on behalf of Kim to comment further on the school’s fundraising efforts during Kim’s presidency.