Public colleges to provide mental health services similar to Columbia’s

September 6, 2019

Public colleges and universities in Illinois will be required to catch up to Columbia and other private colleges when it comes to providing mental health and suicide prevention services.

Under the Mental Health Action on Campus Act, signed into law by Gov. J.B. Pritzker last month, Illinois colleges will now partner with local mental health services and provide peer support to students.

The new law, which takes effect in January 2020, requires public universities and colleges to make information on all mental health and suicide prevention resources at the school available to its students.

The act is designed to raise mental health awareness on campuses by designating a panel, appointed by the institution’s board of trustees, to implement policies that advise students, faculty and staff on procedures for help- ing students who may exhibit signs of mental health conditions, such as anxiety or depression.

Illinois State Sen. Iris Martinez, the chief Senate sponsor of the bill, said it will affect the way mental health and suicide prevention is tackled on college campuses.

“We are becoming more aware of the struggles college students are facing,” Martinez said in a May press release when the legislation was passed by the Senate. “They need to be able to readily access help for mental health issues they may be dealing with.”

Columbia, a private college not covered under state law, already provides many of the services now required by public colleges and universities. Private institutions such as Roosevelt, Loyola and DePaul universities o er psychological and psychiatric treatments and mental health screenings.

Roosevelt University’s Counseling Center offers a variety of services to raise mental health awareness through presentations, brochures and programs throughout the school year, according to the school’s website. The Counseling Center also employs student workers called Peer Advocates.

At Columbia’s Counseling Services, there are various hotlines, therapy referrals for other students, free individual therapy and unlimited group therapy sessions for students dealing with issues ranging from adjusting to college life to an abusive relationship.

“We realize that students might encounter difficult situations that could impede their academic, personal and social progress,” according to the Counseling Services’ website. “Our services are designed to help these students address their concerns and increase their self-aware- ness while empowering them to manage challenging areas in their lives.”

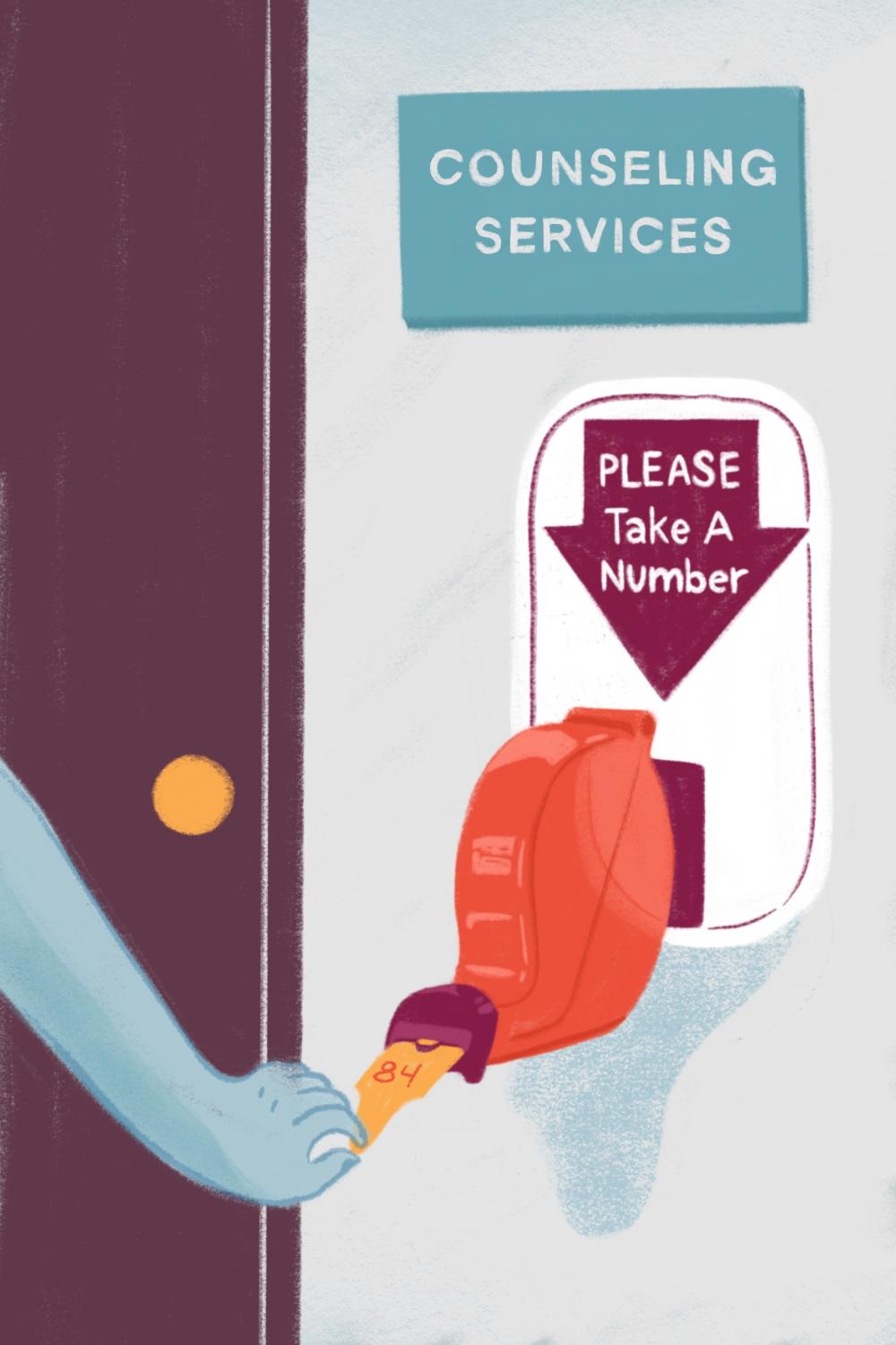

Some students at Columbia however, have pointed to flaws in Counseling Services such as difficulty in finding resources and long wait times for a therapy session, as reported by The Chronicle January 2019.

Senior graphic design major Hannah Meyers went to Counseling Services her junior year and was put on a waiting list.

“It kind of is a little bit of a process getting into the Counseling Service,” Meyers said. “You had to get put on a waiting list because there were so many people that were signed up. So, I had to wait a while and then you have to do an initial session where they’re asking you a bunch of questions about why you’re coming in.”

“In some ways, this bill, which was passed by overwhelming margins, is kind of a commonsense of proof to sort of say, ‘Let’s arm our students to be supporters for each other,’” said Robin Fretwell Wilson, director of the Epstein Health Law and Policy programs at the University of Illinois College of Law.

By adding peer groups, the Act is making discussions around mental health more accessible to anyone interested in learning more.

“[This Act] provides funding to expand mental health services on campus, but it also requires that programs show they’re going to do this in an innovative way that will actually [break down] some barriers … that have gotten in the way of mental health services,” said Marc Atkins, a psychiatrist, professor of psychology at the University of Illinois at Chicago and the director of the Institute for Juvenile Research at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

According to a study published online in 2018 in Depression and Anxiety by Harvard Medical School researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, at least one in five students of the 67,000 surveyed from more than 100 institutions have thought about suicide.

“Students on campus, perhaps more than most, experience ups and downs in their mental health,” Atkins said. “They deal with stress, they deal will relationship issues, they’re under a lot of pressure being away from home depending on the campus and so on.”

Heidi Dueweke, a licensed clinical professional counselor at Bergen Counseling Center, also works part-time with a nonprofit called Thresholds, a community based mental health organization. Dueweke is a Certified Recovery Support Specialist for Thresholds and said it can be beneficial for peers to talk to each other because they may be able to relate more.

“Being able to talk with someone that’s had similar struggles, and can really understand where another person’s coming from really can help develop a sense of empowerment and hope in that, ‘I’ve been there and I’ve been able to come through the other side and you can, too,’” Dueweke said.