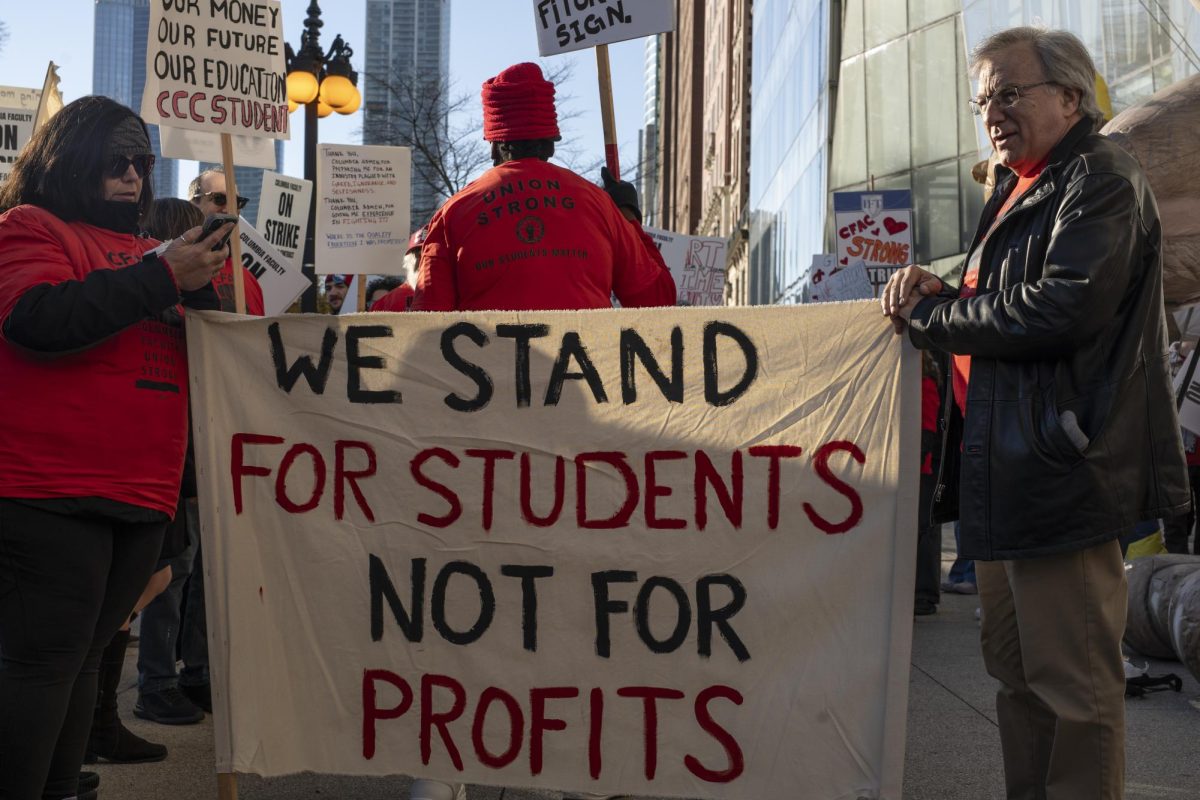

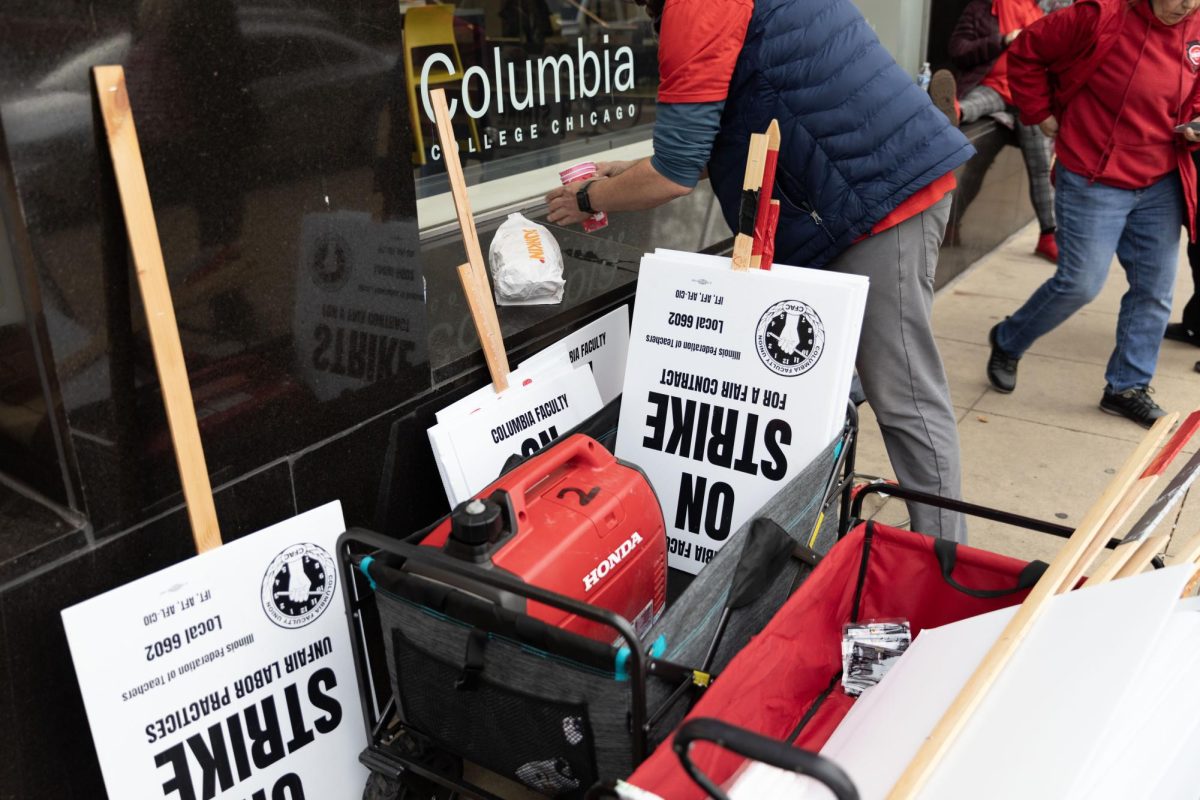

On the first day of their strike on Oct. 30, dozens of Columbia’s part-time faculty union marched in front of the 600 S. Michigan Ave. building and picketed in front of other campus buildings around the South Loop.

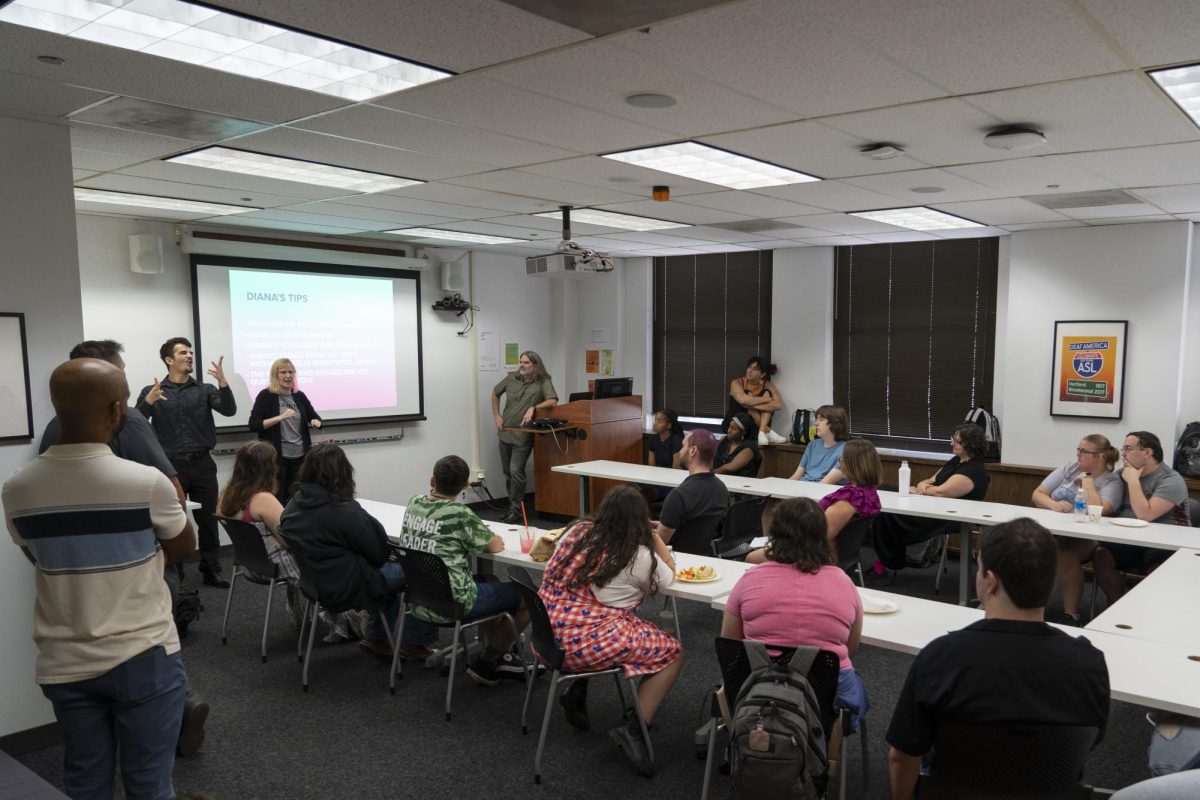

Many of the classes taught by part-time faculty were canceled, and the hallways and classrooms were quieter than typical of a Monday when more than 500 course sections are scheduled, the majority of them taught by part-time faculty.

Some full-time faculty – who are not part of a collective bargaining unit – moved their classes to Zoom, while others held classes on campus. Some part-time instructors also taught in spite of the strike.

At a press conference in the morning, part-time faculty union President Diana Vallera called Columbia “shameful” for not having safety nets for part-time faculty like healthcare and job security. Such benefits are rare for part-time faculty.

“We want them to come back to the table, but let’s be clear: We want them to come back to the table and negotiate in good faith,” Vallera said. “They can’t come back and just simply say ‘no’ and that’s all they say.”

The next bargaining session between union and college representatives will be in the afternoon on Tuesday, Oct. 31, said Chief of Staff Laurent Pernot.

“We hope there will be a resolution as soon as possible,” Pernot told the Chronicle. “We are meeting with the union tomorrow, but the ultimate decision about striking rests with the union.”

The Columbia College Faculty Union, or CFAC, announced the strike after a bargaining session on Oct. 26 broke down. It was livestreamed on an Instagram account reportedly belonging to the union and an unspecified “CCC Student Body Coalition.”

There are multiple demands the union is making to end their strike, but course cuts and increased class sizes are at the top of the list. The union wants to be able to veto those changes. Other demands include the immediate removal of President and CEO Kwang-Wu Kim and Senior Vice President and Provost Marcella David, a tuition freeze and an DEI ombudsman position.

The college has said it needs to take certain measures to reduce a $20 million deficit.

Speaking at the union press conference, Guo-Jian Swartz, a junior film and television major with a producing concentration, said he came to Columbia for small class sizes and close mentorship with industry professionals.

“The backbone of Columbia is made with part time faculty, said Swartz, one of three students who spoke. “Without them, this institution would not be here today. Since my time here, that mission statement is fading away and fast.”

He said this isn’t the first time he has done community activism. He worked with March for Our Lives, a student-led organization fighting for stronger gun legislation and gave a speech for them as well.

“When I go into speech, I like to think about the facts, make sure we get those straight,” Swartz said.

Swartz said that he wrote the strike speech himself but sent it to union leadership to look over. He said he was invited to speak at the press conference by union Vice President Lisa Formosa-Parmigiano, a part-time instructor in the Cinema and Television Arts Department.

There are currently 584 part-time instructors at the college, and 221 full-time professors.

Dozens of students told the Chronicle that they support the strike and will not attend classes until it is over, even if their courses are taught by full-time professors or by substitute instructors.

“I very much do not agree with what our president is doing, so I think it’s good that they’re going on strike,” said Stacia Earle, a sophomore audio arts major. “We have to do what we can do and I think this is one of the tactics we can use to get the executives of this place to hopefully make a change.”

The union ordered part-time professors to strike or face disciplinary action and said if full-time faculty fill in for part-time faculty, they would be considered “scabs,” a derogatory term for someone who crosses a picket line during a strike.

“I think we’re always hopeful if the administration will bargain fairly,” said Timothy McCain, a part-time theatre instructor. “It isn’t just one thing that we’re looking for. People think that we’re striking about [only] money; that the union is always wanting more money. It’s also about work conditions and also teaching.”

The last time CFAC went on strike was in 2017, over similar concerns and demands of financial transparency. That walkout lasted two days. The union averted a strike in April 2019 after settling with the college.

Its current contract expired at the end of August.

“What kind of employer slashes the classes, bloats the classroom size of the remaining classes, lays off one-third of the adjunct faculty and gives themselves fat bonuses and then tells the union, we’re not going to talk about it?” said Robert Bloch, the union’s lawyer. “We’re here today to say no, you will listen to us. Listen to your faculty, you will listen to your students. We don’t know how long this strike will take, but remember that every day we stay out, we get stronger, you get stronger.”

Bloch is a former field attorney for the National Labor Relations Board, where the union filed charges against the college on Aug. 25. The union filed an additional charge with the Board on Thursday, Oct. 26, with their attorneys on grounds of the college refusing the furnish information and refusing to bargain in good faith. The first charge was also for refusing to furnish information, as well as “repudiation/modification of contract.” Both cases are currently open.

Students will start registering for Spring 2024 classes on Monday, Nov. 6.

An independent look into the Spring 2024 course schedules by the Chronicle found that class sizes will not jump significantly over Spring 2023 despite student worries and the union’s claims.

But some classes have already increased. McCain, the part-time theatre instructor, taught Theatre Survey II: American Drama last spring with 85 students. The course cap was 90. Another 90-seat section had 55 students.

“It was really difficult because there are going to be some students who are going to be able to take on that challenge of just having me lecture to them, but there’s no way to be able to be hands-on with them,” McCain said. “It’s hard to get to know them really well. Say a student has a learning disability. There’s a system that’s setup to say a student has a learning disability but where do I have the time to work with that student to help them … to get them to succeed in the class.”

The same class is scheduled for Spring 2024, again with two sections capped at 90. Another part-time instructor and a full-time instructor are scheduled to teach them and not McCain.

Additional reporting by Robin Sluzas and Connor Dore.