Some full-time faculty began stepping in to cover for part-time instructors out on strike, even though the college has yet to share details about how students will be graded in classes that haven’t met for three weeks.

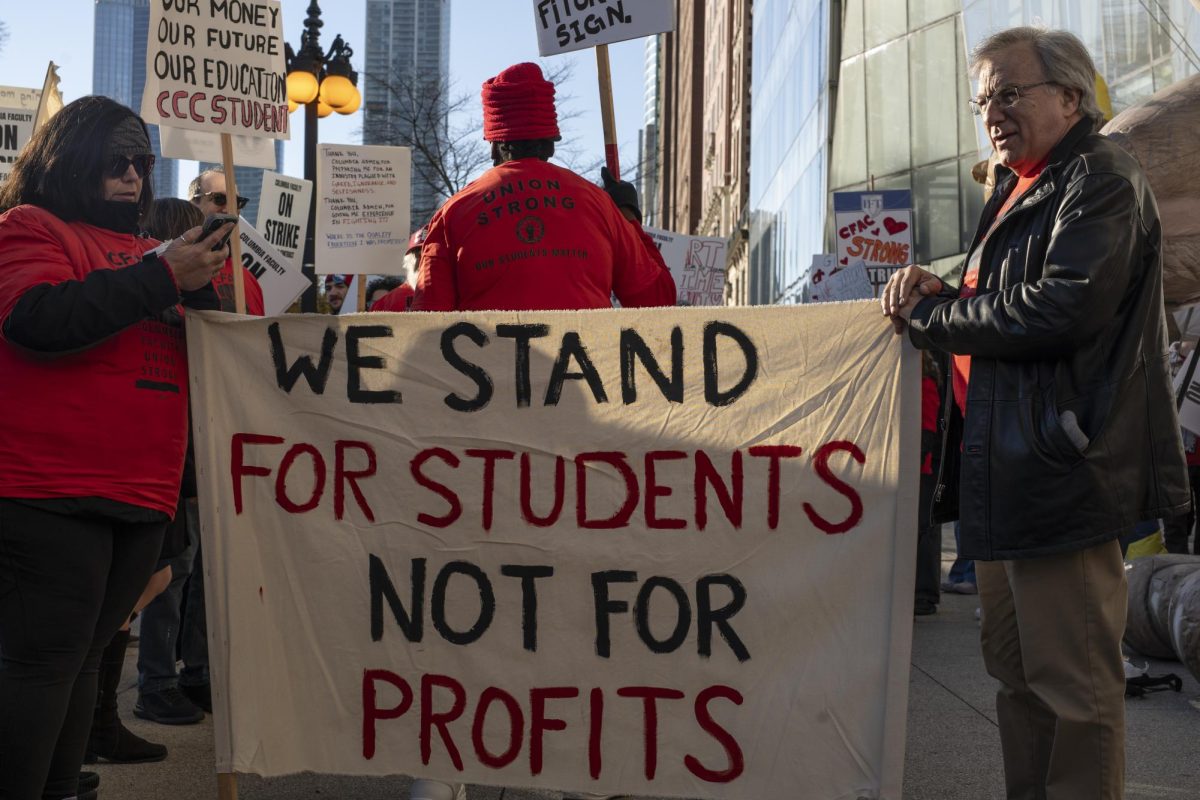

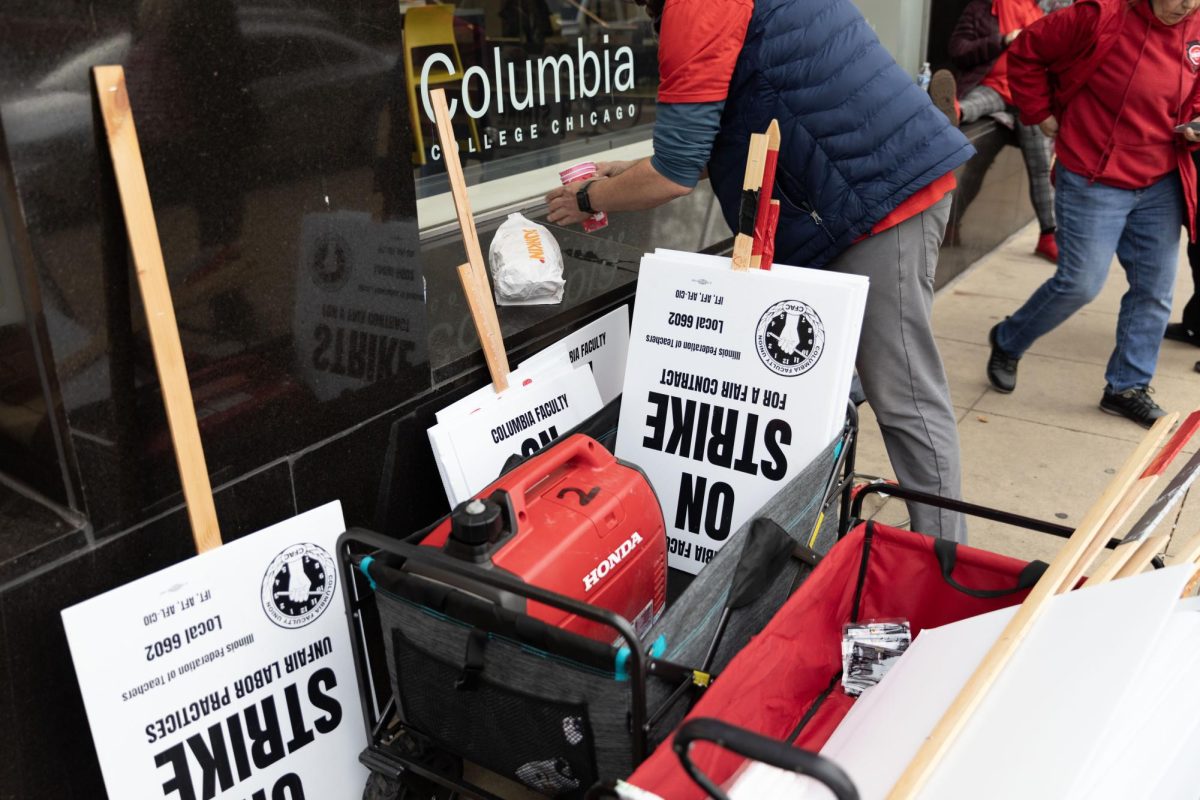

The Columbia Faculty Union, which represented 584 part-time instructors at the start of the fall semester, has been on strike since Oct. 30. Hundreds of classes have not met for three weeks, and students have not heard from their instructors.

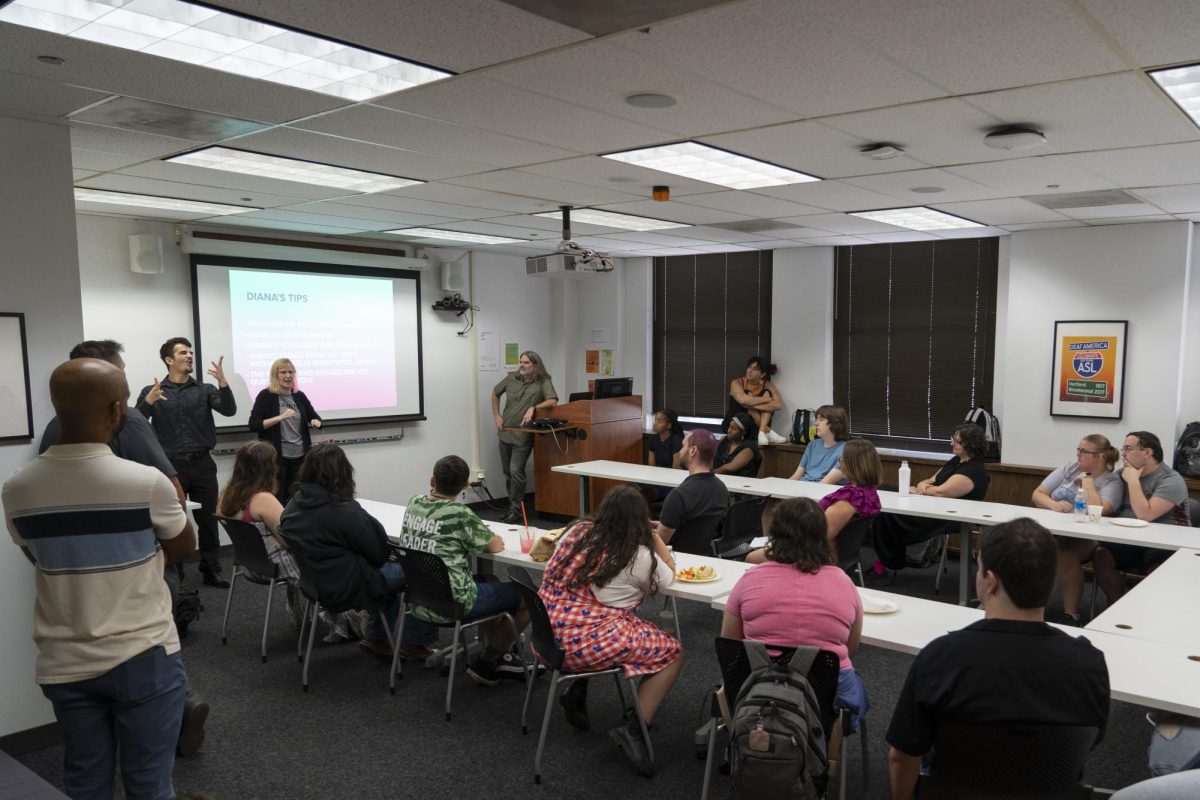

Some striking instructors began removing content from their courses at the direction of the union, a part-time instructor told faculty in a meeting of the American Association of University Professors on Friday, Nov. 17. The group is an advocacy chapter because Columbia’s 221 full-time faculty are not part of a bargaining unit.

Assistant Science and Mathematics Professor Derick Jones Jr. said they feel “disheartened” by the situation faculty are in.

“Full-time faculty get more work, I feel that is something that needs to be brought up and talked about and mental health and work balance, work-life balance, we have to think of those things,” Jones said. “I just hope that we can consider all of what diversity, equity and inclusion means and how that fits into decisions that are being made.”

In an email on Wednesday, Nov. 15, Senior Vice President and Provost Marcella David said the college would begin asking full-time faculty to step in to help students complete courses that part-time faculty stopped teaching.

“I want to assure you that when deans and chairs ask you to step in, it is not with the goal of undermining the union,” she said. “My singular priority is my commitment to student learning and success. Our students need a clear pathway forward that honors our responsibility for their learning, even as we continue to hope for a resolution to end the strike.”

Joan Giroux, an art history professor and president of Columbia’s AAUP chapter, said she asked David to clarify what was being asked of full-time faculty, which includes both tenure-track and tenured faculty, as well as teaching-track.

David said faculty have a choice to teach for part-time instructors, without consequences.

“My request is solely based on my conviction that we need to take immediate action in support of our students and nothing else,” David said in an email shared at the AAUP meeting.

Some faculty expressed concern about how teaching-track faculty will be impacted. Teaching-track are full-time faculty who typically teach four courses per semester and do not have the same scholarship and service requirements as tenure-track or tenured faculty.

The college has 45 teaching-track faculty who hold the rank of assistant, associate and professor of instruction, said Pegeen Quinn, associate provost for academic personnel.

The union has formally proposed to lower the maximum number of teaching-track faculty the college can have, said Lambrini Lukidis, associate vice president of Strategic Communications & External Relations.

“Recently the union has brought up in bargaining that rather than take the current measures impacting part-time faculty the college should eliminate some teaching-track faculty – to which the college said no,” Lukidis told the Chronicle in an email.

Union President Diana Vallera denied to the Chronicle that the union made that request. “No, of course not,” she said in an email asking about it.

Matt Cunningham, an assistant professor of instruction in the Communication Department, said he does “a lot above and beyond just teaching my classes.”

“Even though technically I’m not supposed to be a part of curriculum development because I’m supposed to be teaching, I have been because there are no other faculty members in the radio program,” Cunningham said.

He also said he was “shocked” that the union would target teaching-track faculty because they had been courting him to join the union over the summer.

“Most of our adjunct faculty’s roles are teaching, but they have jobs outside of that if this isn’t their profession,” he said. “It’s our job, our profession to be instructors. We’re on committees, we help develop things. We’re working on other things besides just being in the classroom. We’re here supporting students in other ways, and that would go away if we weren’t here teaching.”

He worried about who would fill that role. “Because part-time faculty come in, teach their class and leave,” he said. “I’m not saying they don’t support their students, but they don’t support the college so who’s going to do those roles?”

During a union Zoom call for students and parents late Thursday night, Nov. 16, several teaching-track faculty reported that they were removed from the call.

The provost’s office, along with the Faculty Senate, is in the process of determining how students will be graded as the strike continues. David and President and CEO Kwang-Wu Kim already have told students that they will receive credits for their courses. One likely option is that students will be able to take a course pass/fail as they did during at the start of the pandemic.

Part-time faculty teach the majority of class sections at Columbia.

Students protested this week demanding some tuition reimbursement for the missed time. In a faculty forum, Kim said he had not ruled that option out.

Associate Professor of Cinema and Television Arts, Michael Caplan, who was on the bargaining team for the first CFAC contract in 1999, said while he has seen protests at Columbia before, never anything like this.

“The length is a result of the distance between the two sides and the level of visible and public animosity,” Caplan said.

On Thursday, Nov. 16, CFAC sent an email to some faculty and staff telling them they have been asked “to walk into our classrooms, undermining our strike action.”

“We ask you to make a better choice,” the union’s email said. “Stand with us. Do not let the administration make a scab of you.”

The college has been talking about the need to address its financial deficit since last spring, but faculty learned more concrete details about how it would do that at the back-to-school meeting in mid-August.

At that time, David said the college would lower its enrollment targets and become a smaller school.

Faculty also were told that some class sizes, mostly in foundational or survey courses, would increase. Sections of courses also were reduced.

The union filed unfair labor charges over those moves and ultimately walked out over them.

Art history professor Amy Mooney said she has seen “significant changes” in her department.

Mooney told faculty members at the meeting on Friday that next semester’s “Introduction to Visual Culture” class that is “designed to serve first-semester, first-year students” was originally capped at 18 students. She said the department agreed to bump it up to 22 students; it will now be capped at 44.

This is in addition to “Contemporary Art: 1980 to the Present,” which Mooney said is usually enrolled at 35 but will now have 80 students.

Additional reporting by Uriel Reyes and Olivia Cohen.