Chicagoans’ health problems vary by neighborhood

April 3, 2017

Select Chicago neighborhoods are not receiving equal access to healthcare, resulting in neglect of residents’ health needs, according to March 23 Sinai Community Health study.

“Health equity is about everybody having an equal opportunity regardless of race, gender, age, socioeconomic status or sexual identity to reach their full potential,” said Raj Shah, associate professor at Rush University Medical Center and co-director of the Center for Community Health Equity. “We’re still needing to find solutions for why we’re not closing the gaps.”

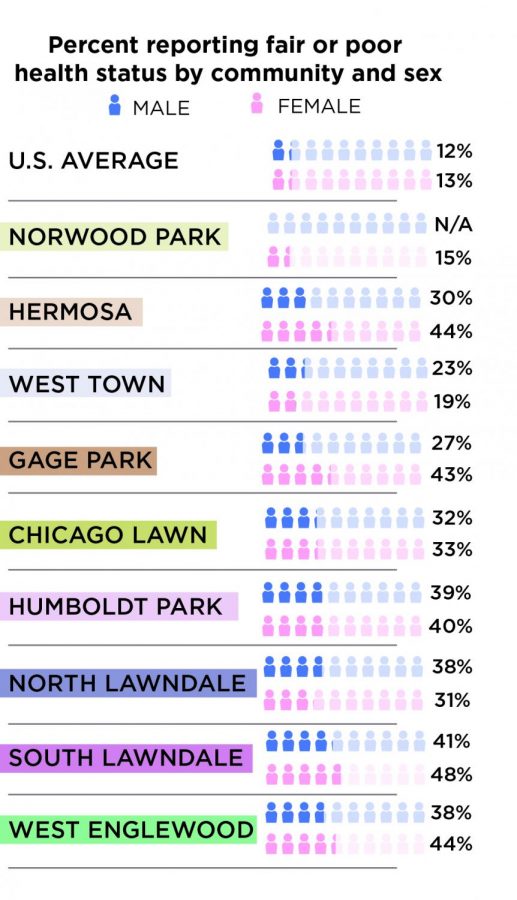

The study surveyed nine neighborhoods of varying socioeconomic makeups including Norwood Park—an area with a median household income of over $75,000—Hermosa, Humboldt Park, West Town, Gage Park, Chicago Lawn, West Englewood, South Lawndale and North Lawndale which has a median household income of less than $22,000.

The study polled the neighborhoods in categories such as current health status, common diseases, smoking habits, food insecurity and health insurance coverage.

The Sinai Community Health Institute was not available for comment as of press time.

José Luis Rodríguez, project coordinator for the Greater Humboldt Park Community of Wellness, said community residents struggle with issues of diabetes, hypertension, mental illness and obesity—reflected in the study, which labeled 56 percent of women and 41 percent men in Humboldt Park as obese.

“It’s more than one issue to address,” Rodríguez said. “We’re still far in terms of being able to find something that is holistic in addressing a lot of these issues.”

Shah said there has been an increase in the measures of health and well-being, but because of health disparities, the distribution is not equal. An example is life expectancy: Chicagoans average 85 years, but for some neighborhoods, the figure dips into the late 60s. Having a 16–18-year gap in life expectancy only a few miles apart is concerning, he added.

Clinical care comprises only about 20 percent of overall health, said Dominique Williams, LISC Chicago program officer, an organization that aims to “bridge the gap” for community organizations to access the care they need. The other 80 percent, she said, includes health behaviors and social and economic factors in the physical environment.

SCH also polled exposure to domestic violence, social cohesion and neighborhood safety, something Williams said needs to be addressed through multiple platforms.

“It’s really going to take a multistep collaborative approach to [have communities be healthier],” Williams said. “Doctors, nurses and hospitals can’t do it alone.”

Williams said a big part of what drives personal health are factors like a person’s local environment.

It is a major issue for tenants to hold landlords accountable to create healthy environments for the people living in their buildings, said Rev. Larry Dowling, a member of the Community Renewal Society and pastor for St. Agatha Church in North Lawndale. Landlords are taking advantage of their tenants in low-income communities, he added.

“Whenever we talk about affordable housing, I always have to add the term ‘livable’ housing as well,” said Dowling, whose group advocates for social and economic justice. “There’s a lot of affordable housing, but from places I’ve been in, I would never put anyone in these houses because of the conditions.”

Health disparities across the city are not new, Shah said, and health research has been conducted in Chicago since 1902—revealing that these issues have been in the same neighborhoods consistently. Chicago has been good at describing the issue, but finding a solution has been difficult.

To find a solution, every stakeholder must understand what is happening and engage in collective action to solve the problems locally.

Blanket policies are ineffective in this situation because the report shows each city neighborhood has its own needs, and a solution for one neighborhood may not help another, Shah said.

“We will only solve these problems once we remove the stigma and the lack of information,” Shah said. “Then start getting individuals facing the problems in their own communities to build a civic trust and alliances to work through issues by neighborhood.”