Connecting Columbia’s Urban Campus

Commuters struggle to engage

April 28, 2014

Last Friday evening on campus, students could have watched independent films by Master’s candidates in the Cinema Arts & Science Department, gone to a play about Mary Stuart, Queen of Scotts, attended a reception at the Glass Curtain Gallery, participated in a culture night sponsored by the Latino Alliance or watched musical performances by graduating seniors. That is, if they stayed on campus. But odds are most students didn’t make the trip and stayed home in their respective neighborhoods.

They are probably in the same boat as Annie Gaskell, a sophomore art + design major who commutes from Pilsen to campus on the Pink Line every day and says she no longer feels as connected to Columbia as she did in her first year.

“Columbia is not your traditional school, but that’s what the appeal and disadvantage of Columbia is,” Gaskell said.

She said she noticed a big difference in how connected she felt to campus after she moved out of the dorms. Last year, she relished her five-minute stroll from the University Center, 525 S. State St., to her classes. This year, she combines a 15-minute walk with a 30-minute train ride five days a week before arriving in the South Loop, which makes coming to campus a time-consuming chore.

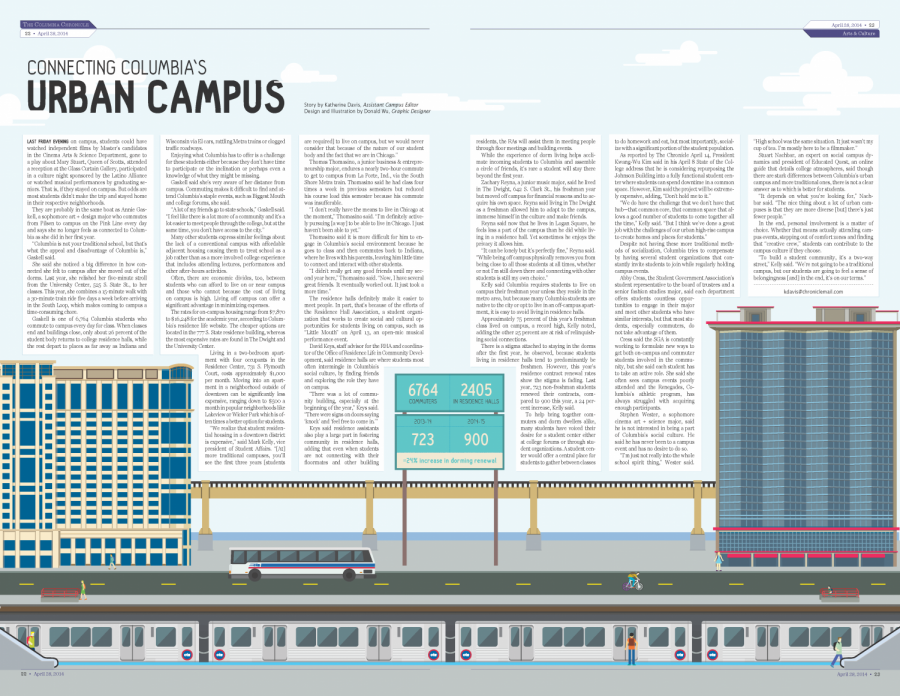

Gaskell is one of 6,764 Columbia students who commute to campus every day for class. When classes end and buildings close, only about 26 percent of the student body returns to college residence halls, while the rest depart to places as far away as Indiana and Wisconsin via El cars, rattling Metra trains or clogged traffic roadways.

Enjoying what Columbia has to offer is a challenge for these students either because they don’t have time to participate or the inclination or perhaps even a knowledge of what they might be missing.

Gaskell said she’s very aware of her distance from campus. Commuting makes it difficult to find and attend Columbia’s staple events, such as Biggest Mouth and college forums, she said.

“A lot of my friends go to state schools,” Gaskell said. “I feel like there is a lot more of a community and it’s a lot easier to meet people through the college, but at the same time, you don’t have access to the city.”

Many other students express similar feelings about the lack of a conventional campus with affordable adjacent housing causing them to treat school as a job rather than as a more involved college experience that includes attending lectures, performances and other after-hours activities.

Often, there are economic divides, too, between students who can afford to live on or near campus and those who cannot because the cost of living on campus is high. Living off campus can offer a significant advantage in minimizing expenses.

The rates for on-campus housing range from $7,870 to $16,248 for the academic year, according to Columbia’s residence life website. The cheaper options are located in the 777 S. State residence building, whereas the most expensive rates are found in The Dwight and the University Center.

Living in a two-bedroom apartment with four occupants in the Residence Center, 731 S. Plymouth Court, costs approximately $1,000 per month. Moving into an apartment in a neighborhood outside of downtown can be significantly less expensive, ranging down to $500 a month in popular neighborhoods like Lakeview or Wicker Park which is often times a better option for students.

“We realize that student residential housing in a downtown district is expensive,” said Mark Kelly, vice president of Student Affairs. “[At] more traditional campuses, you’ll see the first three years [students are required] to live on campus, but we would never consider that because of the nature of our student body and the fact that we are in Chicago.”

Thomas Thomasino, a junior business & entrepreneurship major, endures a nearly two-hour commute to get to campus from La Porte, Ind., via the South Shore Metra train. Thomasino said he had class four times a week in previous semesters but reduced his course load this semester because his commute was insufferable.

“I don’t really have the means to live in Chicago at the moment,” Thomasino said. “I’m definitely actively pursuing [a way] to be able to live in Chicago. I just haven’t been able to yet.”

Thomasino said it is more difficult for him to engage in Columbia’s social environment because he goes to class and then commutes back to Indiana, where he lives with his parents, leaving him little time to connect and interact with other students.

“I didn’t really get any good friends until my second year here,” Thomasino said. “Now, I have several great friends. It eventually worked out. It just took a more time.”

The residence halls definitely make it easier to meet people. In part, that’s because of the efforts of the Residence Hall Association, a student organization that works to create social and cultural opportunities for students living on campus, such as “Little Mouth” on April 13, an open-mic musical performance event.

David Keys, staff advisor for the RHA and coordinator of the Office of Residence Life in Community Development, said residence halls are where students most often intermingle in Columbia’s social culture, by finding friends and exploring the role they have on campus.

“There was a lot of community building, especially at the beginning of the year,” Keys said. “There were signs on doors saying ‘knock’ and ‘feel free to come in.’”

Keys said residence assistants also play a large part in fostering community in residence halls, adding that even when students are not connecting with their floormates and other building residents, the RAs will assist them in meeting people through floor meetings and building events.

While the experience of dorm living helps acclimate incoming students to Columbia and assemble a circle of friends, it’s rare a student will stay there beyond the first year.

Zachary Reyna, a junior music major, said he lived in The Dwight, 642 S. Clark St., his freshman year but moved off campus for financial reasons and to acquire his own space. Reyna said living in The Dwight as a freshman allowed him to adapt to the campus, immerse himself in the culture and make friends.

Reyna said now that he lives in Logan Square, he feels less a part of the campus than he did while living in a residence hall. Yet sometimes he enjoys the privacy it allows him.

“It can be lonely but it’s perfectly fine,” Reyna said. “While being off campus physically removes you from being close to all those students at all times, whether or not I’m still down there and connecting with other students is still my own choice.”

Kelly said Columbia requires students to live on campus their freshman year unless they reside in the metro area, but because many Columbia students are native to the city or opt to live in an off-campus apartment, it is easy to avoid living in residence halls.

Approximately 75 percent of this year’s freshman class lived on campus, a record high, Kelly noted, adding the other 25 percent are at risk of relinquishing social connections.

There is a stigma attached to staying in the dorms after the first year, he observed, because students living in residence halls tend to predominantly be freshmen. However, this year’s residence contract renewal rates show the stigma is fading. Last year, 723 non-freshman students renewed their contracts, compared to 900 this year, a 24 percent increase, Kelly said.

To help bring together commuters and dorm dwellers alike, many students have voiced their desire for a student center either at college forums or through student organizations. A student center would offer a central place for students to gather between classes to do homework and eat, but most importantly, socialize with a significant portion of the student population.

As reported by The Chronicle April 14, President Kwang-Wu Kim said in his April 8 State of the College address that he is considering repurposing the Johnson Building into a fully functional student center where students can spend downtime in a common space. However, Kim said the project will be extremely expensive, adding, “Don’t hold me to it.”

“We do have the challenge that we don’t have that hub—that common core, that common space that allows a good number of students to come together all the time,” Kelly said. “But I think we’ve done a great job with the challenges of our urban high-rise campus to create homes and places for students.”

Despite not having these more traditional methods of socialization, Columbia tries to compensate by having several student organizations that constantly invite students to join while regularly holding campus events.

Abby Cress, the Student Government Association’s student representative to the board of trustees and a senior fashion studies major, said each department offers students countless opportunities to engage in their major and meet other students who have similar interests, but that most students, especially commuters, do not take advantage of them.

Cress said the SGA is constantly working to formulate new ways to get both on-campus and commuter students involved in the community, but she said each student has to take an active role. She said she often sees campus events poorly attended and the Renegades, Columbia’s athletic program, has always struggled with acquiring enough participants.

Stephen Wester, a sophomore cinema art + science major, said he is not interested in being a part of Columbia’s social culture. He said he has never been to a campus event and has no desire to do so.

“I’m just not really into the whole school spirit thing,” Wester said. “High school was the same situation. It just wasn’t my cup of tea. I’m mostly here to be a filmmaker.”

Stuart Nachbar, an expert on social campus dynamics and president of Educated Quest, an online guide that details college atmospheres, said though there are stark differences between Columbia’s urban campus and more traditional ones, there is not a clear answer as to which is better for students.

“It depends on what you’re looking for,” Nachbar said. “The nice thing about a lot of urban campuses is that they are more diverse [but] there’s just fewer people.”

In the end, personal involvement is a matter of choice. Whether that means actually attending campus events, stepping out of comfort zones and finding that “creative crew,” students can contribute to the campus culture if they choose.

“To build a student community, it’s a two-way street,” Kelly said. “We’re not going to be a traditional campus, but our students are going to feel a sense of belongingness [and] in the end, it’s on our terms.”