City provides support for mental health crises

City provides support for mental health crises

September 11, 2017

Chicago is improving services for people with mental illnesses by strengthening crisis response and awareness training, according to an Aug. 30 press release from Mayor Rahm Emanuel.

A mayoral pilot initiative by the Citywide Mental Health Steering Committee has trained more than 500 residents from Austin, Garfield Park and North Lawndale. They learned of the support services the city offers, how to identify the signs of a mental health crisis, and request a Crisis Intervention Team trained police officers to de-escalate these situations.

“We want to make sure there’s a comprehensive approach to improving the way we interact with all of our residents,” said Kelly O’Brien, executive director of the Illinois Kennedy Forum—an organization that provided training and works to end discrimination against individuals with mental health challenges. “Not only are there improvements that police and first responders need to do, but the community has a role as well.”

A May 2015 report from the National Alliance on Mental Illness Chicago shows that 38.5 percent of adults in Illinois reported poor mental health, 16.68 percent were living with a mental illness and 3.37 percent were living with a serious mental illness. The study also shows 60 percent of incarcerated individuals meet diagnostic criteria for mental illness.

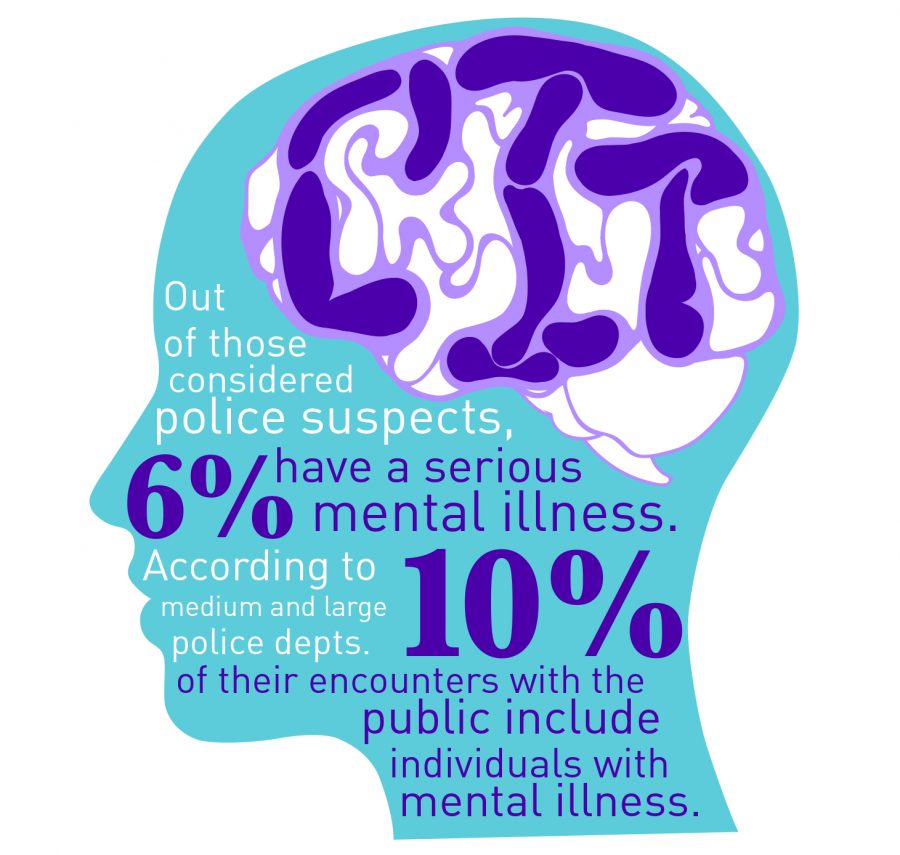

O’Brien said a large portion of the interactions of first responders are with individuals with mental illness. She noted that every community should have this type of training, to see the positive outcomes reflected in the West Side communities extended throughout the city.

The preliminary results of an ongoing evaluation on the training’s effectiveness performed by the University of Illinois at Chicago Jane Addams College of Social Work show that, in the West Side communities, there was decreased stigma associated with mental health and addiction, increased knowledge and comfort in contacting a CIT–trained officer, increased knowledge about mental health, and confidence they could assist someone in need. The final evaluation will be released early 2018.

“We don’t think [only] the police should bear this burden, but we do think they should have had adequate training if they do encounter somebody with a mental health crisis, which is really common in Chicago,” said Alexa James executive director of NAMI Chicago, who also gave training for the project.

Most people do not understand mental health crisis signs and symptoms and, in turn, may see them as criminal behavior when the person in crisis really needs support, James explained.

Michelle Robey, 55, was shot in the abdomen by CPD Feb. 10 after police officers responded to a disturbance at a CVS drug store on Irving Park Road and Western Avenue. Store employees called police when Robey started destroying items, and when police arrived, Robey—armed with a knife—made threatening statements to them. After using a Taser twice to no effect, they fatally shot her.

“It’s one thing to read and learn about it, but when you’re face to face with an individual who has symptoms you’re trying to understand, and they can tell you about their experience and what they need in crisis, then you develop a different level of understanding,” said Martha Mason, director of the Education and Counseling Center at DePaul University.

Mason was involved with CIT training programs for CPD officers more than a year ago and attended meetings where the training was administered. In the eight-hour program, officers learned de-escalation techniques and how to identify someone in a mental health crisis. People diagnosed with chronic mental illnesses spoke with the officers and engaged in role-play to discuss their symptoms in various situations. The officers responded as if they were on a crisis call, Mason said.

Stigmas will decline if communities continue to discuss mental illness, Mason added. Conversations like those on the West Side have allowed people to become more comfortable talking about the issue, which leads to people receiving necessary care, she said.

“It’s crucial to educate the community [and to] start openly talking about mental health because it’s not a dirty word, and it’s something that people don’t have to be embarrassed of,” Mason said.