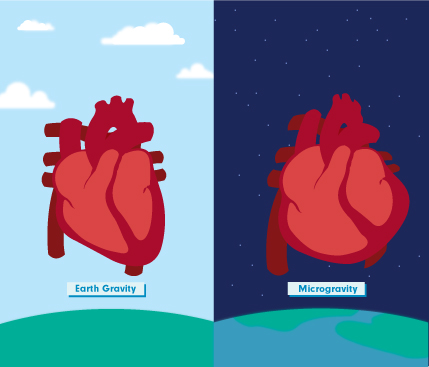

Astronaut hearts shift in microgravity

Astronauts’ hearts take on spherical shape

April 14, 2014

According to recent findings, astronauts experiencing lengthy stays outside Earth’s gravity experience a change of heart—a shape shift to be exact.

A March 29 study presented to the American College of Cardiology analyzed ultrasound images from 12 astronauts during their stays aboard the International Space Station and found astronauts’ hearts take on an unnatural spherical shape after spending extended periods of time in space.

The study did not find any risks associated with the change of shape though, according to Dr. Chris May, lead author of the study and a cardiology fellow at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. May said the shape shift may be due to a loss of muscleb mass in the left ventricle—the heart’s main pumping chamber that shuttles blood to the rest of the body.

According to May, several factors contribute to the shape of the heart while on Earth, including the pericardium—the sac that contains and protects the heart itself—and outside forces that interact with the body, such as gravity.

“Once you lose the force of gravity, the heart takes a more spherical shape,” May said. “We know from prior studies outside of the realm of spaceflight that this is less efficient. It takes more work to have the same amount of blood pumped to the rest of the body.”

The study’s findings do not imply that the change in the heart’s shape is unhealthy, according to Dr. Paul Forfia, director of the Pulmonary Hypertension and Right Heart Failure and Pulmonary Thromboendarterectomy Program at Temple University School of Medicine in Philadelphia.

Forfia said it is too soon to determine whether this shape shift will have negative health effects, adding that it may be a harmless adaptation to the change in pressure and distribution of blood outside of earthly gravity.

May said the shift may be one of many stressors that scientists must consider when analyzing the effects of long spaceflights on astronauts. Other stressors, such as decreased bone density and cardiovascular deconditioning, are addressed by astronauts’ rigorous exercise routines while aboard the International Space Station.

“Loss of bone density and deconditioning—which can result in a drop in blood pressure and other issues upon return to Earth—have been more or less addressed [by astronauts] by vigorous exercise,” May said.

Forfia said the volume of blood that is normally stored in the abdomen and legs when a person is standing upright shifts to the chest in microgravity, which could also account for the added stress on the human heart.

The study’s findings could be informative as to how earth-bound human hearts function under strain, May said.

The study allowed researchers to construct a highly accurate model of the heart, May said, which can be used to mimic disease states and subject the heart to certain stresses to study the effects.

May said people can experience heart failure without noticeable symptoms, and seemingly small stressors such as shifting blood flow or chest pain and pressure could trigger serious problems. A highly accurate model of the functions and structures of the heart could give researchers a deeper understanding of heart disease, May said.