Organizations not thrilled with new CPD license plate readers

Organizations not thrilled with new CPD license plate readers

January 28, 2019

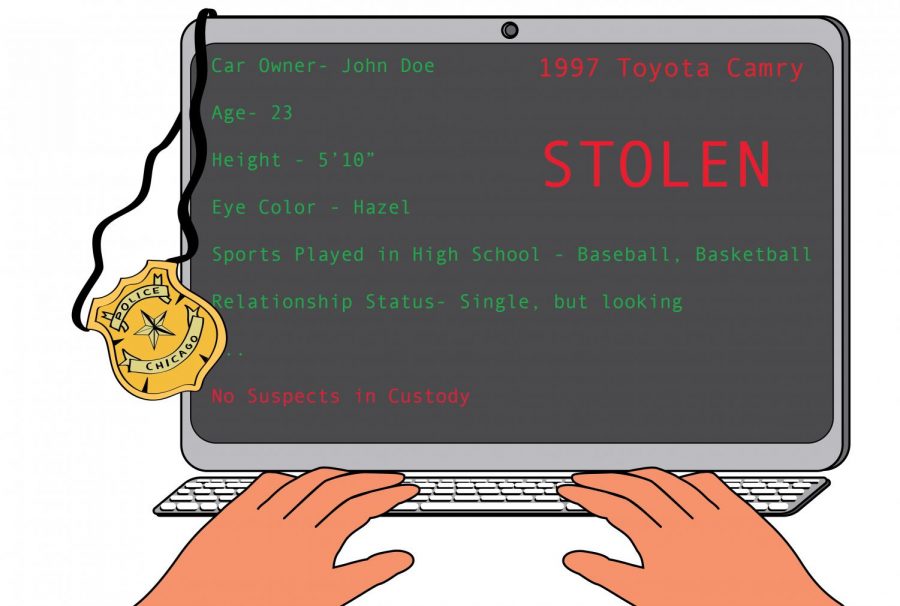

A new program that allows the police to scan license plates and digitally track their data, to help combat the city’s high numbers of carjackings, has come under fire by nonprofit groups that are worried about the new technology invading civil liberties.

License Plate Reader technology will soon be featured on 200 new police vehicles to help combat carjackings beginning this month and finishing in March, according the mayor’s office.

The program centers on License Plate Readers, devices that attach to the top of police cars and scan license plates to record the time, date and location and upload it to a database, said Dave Maass, senior investigative researcher at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit that “defends civil liberties in the digital world.” After the data is recorded, it will be compared with a “hot list” of license plates that are connected to crimes, Maass said.

“Once this information is uploaded to a database, you can go in and [enter] a license plate and get information about where that car has been seen over a period of time,” Maass said. “You can type in an address and see what vehicles have been seen near that address.”

But Maass said there’s a danger that LPR technology may not always be used for the right reasons and may violate civil rights.

Throughout the last year, Maass’ foundation has been filing Freedom of Information Acts with anyone who has been connected to Vigilant Solutions—a developer of LPRs—to see how many license plates were captured and how many were on the “hot list” between 2016 and 2017, Maass said.

In 2016 and 2017, about 133 million license plates were scanned in Chicago. Of these, only .1 percent were attached to crimes, Maass said.

Chicago is not the only city using LPR’s. Cities in several states in the U.S., such as California and Georgia, also use LPR’s.

“We refer to this as a form of mass surveillance,” Maass said. “It is collecting and storing information on everyone, regardless of whether you’re suspected of being involved in a crime. They hold on to it in case one day you do commit a crime.”

Lucy Parsons Labs, a nonprofit that investigates transparency and police accountability, has done investigations about CPD’s use of LPR’s, said Executive Director Freddy Martinez.

One of the things they investigated was where the funding for the LPR’s was coming from, Martinez said. They found that the funding came from civil asset forfeiture, where police can seize property they believe is related to a crime without proving it’s actually related, Martinez said.

Martinez said he doesn’t understand how the new technology can prevent carjackings.

“It’s not going to prevent crime, if anything it’s going to make it easier to recover vehicles after they have been stolen, but it doesn’t actually solve the issue of [prevention],” Martinez said.

Sophomore social media and digital strategy major Karla Sanchez said the LPR’s sound like a good advancement, but she is skeptical about the data being stored.

“Why would you scan everybody’s, especially if [it’s held] on record just in case, [as if] they are waiting for you to slip up,” Sanchez said. “Sharing information that is not associated with any crime or history that they have is just going against privacy.”

The data being collected needs to be monitored to make sure it is being used properly, Maass said. The data should be checked to see why police are searching the license plates, who they are recording and what they are searching for, he added.

“Then when somebody says, ‘I was searching this license plate in connection with a robbery,’ that [will be] the truth and not someone searching it because they wanted to see what their neighbor was up to,” Maass said.

Glenn Daugherty, an assistant professor of justice administration and law enforcement at Western Illinois University and a retired Illinois state trooper, also said there needs to be monitoring to make sure CPD is using the technology for the right reasons.

“Say I find someone who is dating my daughter, and I don’t know anything about him. I go to my buddy who is a police officer, and I have him do a check,” Daugherty said. “Well, you can’t do that because there’s no reason other than for me wanting to know is this guy someone whois safe for my daughter to date.”

According to Maass, the agencies using the LPR data should be more transparent about the information they are collecting and make it more accessible to the public so they can make an educated decision.

“The best thing for us to do for the public is to give them as much information as possible. We can educate them on why we do what we do, so they’re not suspect,” Daugherty said. “If we can follow policy and work for justice and protect the public, then I think it’s all going to work out just fine.”