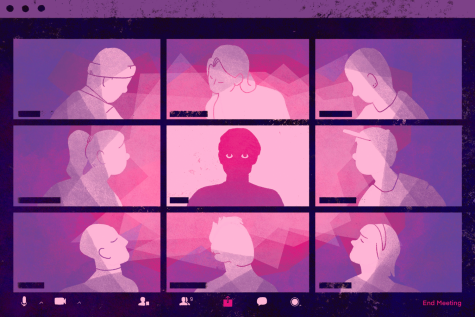

‘Zoombombing’ disrupts online learning, causing anxiety for some instructors

May 21, 2020

Christopher Shaw was ready for his first online “Introduction to Statistics” class to begin, but as students logged onto Zoom, he was struck by a surprise attendee—a Zoombomber.

Shaw, an associate professor in the Science and Mathematics Department, said he did not recognize the Zoombomber, listed as “Bars,” but did not think anything of it because it is common for students to use “silly names,” he said.

Shaw said he unmuted the person’s mic so they could introduce themself when loud, “unintelligible” music began to blare in the background.

Once the anonymous person changed their name to “Chris P. Shaw,” Shaw immediately kicked them out of the meeting, realizing it was a Zoombomber—an uninvited guest who disrupts a virtual meeting through behaviors such as various obscene, violent or offensive images or words.

As schools, businesses and individuals are now relying on the video chat platform to conduct daily communication from home, more instances of Zoombombing are being reported. From Chicago City Council meetings to lectures at Loyola University, no conference is exempt from possibly being Zoombombed.

As Columbia continues to rely on Zoom for online courses through summer and likely into the fall semester, the college is working to prevent Zoombombing.

Kathie Koch, associate vice president and chief information officer at Columbia, said “[Zoombombers] want to … draw attention to themselves.”

Until recently, there was no option to formally report a Zoombombing occurrence at Columbia, giving no clear idea as to how often it has happened thus far, so the only occurrences she is aware of are rumors, Koch said.

As of April 20, instructors have been able to fill out a form to report any problems with Zoom. Once reported, Koch said the instructor will be contacted by Information Technology to confirm the details, and, if available, the report from the meeting will be pulled to log the name and email address used by the Zoombomber to “hold the responsible party accountable.”

Koch said once the link went live, Information Technology has received five tickets regarding Zoomboming attempts from April 17 to April 24. However, she said one reported instance was a “mistake” and the faculty member was able to identify the attendee.

There have been no other tickets filed since April 24.

Faculty can secure their meetings by implementing a password and putting students in a “waiting room” so they can manually accept requests to join, she said.

“[Instructors] control who walks in the door, kind of like standing at the classroom door and saying, ‘Yep, you can come in, you can come in,’ but not letting those that they don’t recognize,” Koch said.

When deciding which platform to use during the transitional planning period, Koch said Zoom was favored over Microsoft Teams or Canvas Conferences because of its easy accessibility for everyone, especially in allowing guest lecturers to join.

The college has not yet discussed whether or not it will renew its plan with Zoom because of future uncertainties concerning the pandemic, Koch said.

Adam Everspaugh, a cybersecurity expert for Keeper Security in Chicago, said it does not take a lot of “sophistication” to Zoombomb a meeting. Often, people will share the intended target’s meeting link as an invite to cause trouble, he said.

Everspaugh said once inside the meeting, the Zoombomber will do anything from what Shaw experienced to screen sharing inappropriate images that make it “too gross or too disruptive to continue” a meeting, so the host will be forced to end it.

Like many Columbia faculty, Greg Foster-Rice, an associate professor in the Photography Department, said he is following the recommended precautions in his classes.

“I use waiting rooms for all of my class meetings,” he said. “Everybody that wants to come in is put into an antechamber, and I’m able to look at their names to determine that, ‘Yes, that’s my student.’”

Foster-Rice said he speculates the college has not been experiencing as many Zoombombings because of the small average class size. Intruders tend to look for meetings with a large number of people that they can disrupt, he said.

Khalid Y. Long, an assistant professor in the Theatre Department, said he did not hold Zoom calls that were mandatory for students because of his fears of being Zoombombed.

During the spring semester, Long instructed two sections of “Theatre Survey II: American Drama,” one of which had more than 100 students.

“I’m just afraid of the results of that,” Long said. “What type of violent and/or traumatic illustrations or videos or messages would we receive? It is something on the back of my mind that gives me severe anxiety.”

Despite the problems Zoom has been facing, Foster-Rice said it is the only option left.

“Unfortunately, realistically this is the only way that I can provide my students with what they need right now,” he said.