Theatre Department’s ‘elephant in the room’ sparks discussion on safe spaces and cancel culture

After presenting their play in the “Playwriting: Advanced” class on Zoom, Estefania Unzueta was stunned when the instructor began to compare one of the Latinx characters in the play to the film term “magical negro.”

Unzueta, a senior advertising and writing for performance double major, texted another student in the class, saying, “Did he really say that?” Unzueta is the only person of color in the class and said the other students were not as bothered.

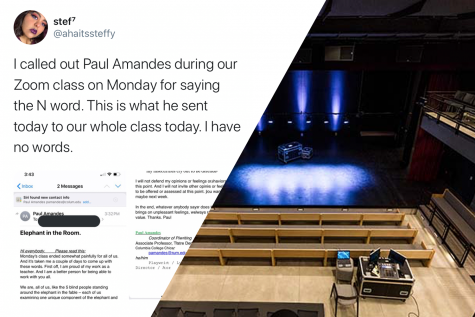

The incident was widely circulated among the Columbia community on social media after Unzueta posted about it, attracting more than 300 likes on Twitter and nearly 40 comments on Facebook. The situation has called into question the issue of safe spaces and cancel culture in an educational setting.

Safe spaces are places where people are not exposed to discrimination or criticism, while cancel culture refers to the group shaming practice of calling someone out on social media for allegedly saying something offensive.

Carin Silkaitis, the Allen and Lynn Turner Chair of the Theatre Department, said the instructor—Paul Amandes, an associate professor in the Theatre Department—teaches about tropes in his class in order to caution against their use.

Amandes did not respond to multiple requests for an interview.

In this incident, Silkaitis said Amandes was commenting on how Unzueta’s Latinx character dies, which often happens to characters of color at the end of plays. Amandes was questioning why these characters need to be sacrificed as a form of cautionary criticism explained by the “magical negro” trope, Silkaitis said.

“He was teaching a pedagogically sound lesson that bothered this particular student,” she said. “So, what if his next lesson bothered another student, and then that student does the same thing to him? … At some point, we’re not going to be able to teach, except for the most banal, safe lesson plans. At that moment, I am no longer interested in doing this for a living.”

Raquel Monroe, co-director of Academic Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, said the student’s social media post about the incident spread misinformation and contributed to cancel culture by claiming the instructor used the “N-word” when he actually used the word “negro” in a scholarly setting.

She applauded Amandes for even teaching the term, which has been attributed to filmmaker Spike Lee, who often talks about his frustrations with this trope.

“To conflate negro with the N-word is a large misstep and completely misses the definition of the term,” said Monroe, an associate professor in the Dance Department. “For the professor to use that language was appropriate, and within the context, incredibly relevant and shows that the professor actually knows what they’re talking about when thinking about people of color.”

Monroe said “magical negro” is a common trope in Hollywood where filmmakers embed a black character with power as opposed to portraying them as a “normal human being that has feelings and a family,” which strips them of their “everydayness and humanity,” making them otherworldly.

This can be seen in films such as “Same Kind of Different As Me,” where a white couple’s lives are changed when they befriend an extraordinarily wise black homeless man.

Khalid Y. Long, an assistant professor in the Theatre Department, said “magical negro” is a pedagogical term used in this situation as a teaching moment about racial dynamics within media culture, not as a derogatory term.

“Not only is teaching hard, but what makes it hard is the subject matters,” Long said. “If I am a teacher who considers myself a cultural historian but also as an activist who uses theatre and performance in the classroom as my realms of activism, then we’re going to have tough conversations … about our American history and within our current contemporary moment.”

He added that posting about the incident on social media was not “professional” and was misleading.

https://twitter.com/ahaitssteffy/status/1258136487725596673

“I hope that this is a learning moment and a teaching moment for everyone involved and [does] not become … bigger than what was intended or needed to be,” Long said. “The lesson is to hold up and listen, make sure we’re aware of what the professor is intending to do and put things in proper context.”

Silkaitis said dozens of students have emailed or had conversations with her after seeing Unzueta’s post on Twitter, all of whom spoke out in support of Amandes as a professor who pushes diversity in his classes.

At the end of Unzueta’s Monday, May 4 class, Unzueta approached Amandes about the use of the term.

“He was very defensive,” Unzueta said. “He’s like, ‘Well, that’s not the N-word I know,’ ‘You’re not correct,’ things like that. He tried to fight me on that, and I didn’t feel like arguing with him. So, I told him, ‘I’m not arguing with you. It’s just wrong.’”

Ahead of the next class on the following Wednesday, Amandes sent an email to students in the class with the subject line “Elephant in the Room.”

“We are, all of us, like the 5 blind people standing around the elephant in the fable—each of us examining one unique component of the elephant and believing that component describes the complex animal entirely,” Amandes said in the Wednesday, May 6 email. “With life experience, you may get to know 3 or 4 components; few people get to know them all. So, we all want to win the Elephant-Describing Contest. We want to be right and to be respected for being right. But, there are always blind spots for all of us.”

He added in the email to students that he was “struggling with not taking other people’s behavior toward me personally” and that he would not defend his opinions, feelings or behaviors or invite others to do so at this time but “if you want—maybe next week.”

Unzueta did not attend class the day of the email because they felt like he was trying to silence them or deflect blame.

Unzueta also approached Silkaitis about the incident, but Unzueta said it went “pretty awful.”

“She would compare a lot of [Amandes’] microaggressions to things that happened to her as a queer woman,” Unzueta said. “But [Silkaitis] is a white woman. So, she kept comparing that, as if it’s a bonding experience to have oppression. … That’s not what’s going on here; this is someone with a position of power over me.”

Silkaitis said her experience as a queer woman came into the conversation when she asked Unzueta if she, as a queer woman who is a sociopolitical activist, said something wrong or offensive, should she be canceled and Unzueta said yes, which Silkaitis said she disagreed with.

Instead, Silkaitis said people need to call others out in a constructive way instead of contributing to cancel culture.

“I want to help faculty grow. I want to dismantle systems of oppression to make our classrooms truly inclusive and safer for our students,” Silkaitis said. “I want to have conversations with students and faculty in safely moderated spaces. We have done that this year in the Theatre Department and it’s starting to make a difference. That work does take time, and yes that can be frustrating. But simply canceling people who are working hard to create safer spaces is not the answer.”

She added that the student, and some on social media, wanted the professor fired.

“Let me say that again,” Silkaitis said. “The student wanted the professor fired for teaching about the trope of the ‘magical negro.'”

Rather than relying on students to approach a professor or department chair when uncomfortable, Monroe said DEI is working with faculty to start initiating conversations in classrooms on day one to discuss what language students consider acceptable or not acceptable so they feel heard and respected. However, she said that conversation needs to take into account freedom of expression and course goals without promoting censorship.

“[Do] not let the language become what the class is about,” Monroe said. “No one wants to erase history. In fact, we need to explore history more. In fact, if we explored history more, we would know negro and the N-word are not the same.”

Long said instructors and students need to come to a place where they can talk about these subject matters in a scholarly sense without creating animosity. Rather than contributing to cancel culture, Long suggested students approach instructors during their office hours to have a valuable, constructive, one-on-one conversation without creating tense or offensive moments.

“I do not believe in the notion of safe spaces but I believe in the notion of critical spaces,” he said. “Before we jump, we have to do work. [Students need] to allow the instructor the space to do the work that they’re intending to do and then if we misunderstand or don’t know what’s happening, then you step up.”