In pursuit of a better future, junior communication major Alexis De Ocampo’s father immigrated to the United States in 1986, followed by her mother seven years later. For them and other Filipinos who left home, “the United States has often been seen as the land of opportunity.”

Growing up, her parents tried to honor their history.

“Not many people were fortunate like me, where their families try to keep their cultures alive, and that’s not even their fault,” she said.

As the second-largest Asian American group in the U.S., Filipino Americans have a longstanding history in the country, dating back to Oct. 18, 1587, when the Spanish galleon Nuestra Señora de Esperanza brought the “Luzones Indios” to the shores of Morro Bay, California.

The U.S. first commemorated the arrival of the first Filipinos to America in 1992. But it took 17 years for Congress to recognize October as Filipino American History Month in 2009.

Since then, the Filipino diaspora has experienced waves of migration driven by economic opportunities, political unrest and the reunification of families.

According to the Pew Research Center, about 4.1 million Filipino Americans live in the U.S. as of 2022. Among that data, 52% are born in the U.S., and the rest are immigrants.

De Ocampo said that she was fortunate.

“My parents have pretty much made it an effort to keep Filipino culture alive in my house,” De Ocampo said. “It was never an issue with ‘you need to assimilate’ or ‘you can’t speak Tagalog in school.'”

Tagalog is one of the major languages spoken in the Philippines and the native language of the Tagalog region, which includes the province of Batangas, where De Ocampo’s parents are from.

Growing up, De Ocampo always knew she was Filipino and went to a diverse school where people didn’t make fun of the Filipino food she brought for lunch. However, she felt like people looked at her differently.

“I did have an issue when it came to seeing other Filipino Americans,” she said, emphasizing the weird dissonance where Filipinos born and raised in the Philippines don’t see her as “Filipino enough.”

With the Filipino American population growing, the experiences of newer generations reveal a complex cultural landscape. While some Filipino American youth navigate their dual identities with ease, others face significant challenges.

They often struggle with the perception of being “too Filipino” or “too American,” leading to a sense of disconnect from both their cultural heritage and mainstream society.

This generational divide underscores the varied experiences that shape the identities of Filipino American youth today.

Senior music business major Cali Castillo said that her family immigrated to the U.S. in waves in the 1980s and ’90s. The first wave began with her great-aunt, who eventually petitioned her great-grandfather and great-grandmother, their siblings and their children.

“They kept going on like that, kept petitioning each other and then sponsoring each other,” Castillo said. “Some of them had to get work visas or school visas, and then had to work up to get their papers and whatnot.”

Castillo’s parents came to the U.S. undocumented after her mother got pregnant with her.

“My dad was not gonna leave her,” she said. “So then they stayed, and I was born here.”

Castillo was one of the first of her cousins to be a U.S.-born Filipino American.

“I just petitioned my parents because I turned 21, so now they have their documents, and everything has been set up recently,” she shared. “[They] got their green cards and their passports.”

Castillo believes that all the morals and values she has right now is greatly influenced by how she was raised and the culture she was raised in.

“I was always, always speaking Tagalog, and listening to everybody speak it, and I was always eating Filipino food,” she said. “There was never a time where I would have chosen a slice of pizza over Kare-kare.”

Castillo said she was raised similarly to how her parents were in the Philippines, adding that when it came to raising somebody in America, her parents “didn’t really know how to, they only knew what was like in the Philippines.”

“There’s good and there’s bad in it,” she said. “And now I think I’m very happy with the kind of Filipino American that I am.”

Even though she was raised with strong Filipino traditions, Castillo still believes there are still many stories and cultural lore that she has yet to learn. For her, it’s a two-way street, she also teaches her family about things they don’t know about the culture.

“I didn’t want to be a Filipino growing up in a white culture,” she said. “I always surrounded myself with white kids who were rich and had bigger houses and had straight hair, so I kind of didn’t have anybody around me that looked like me or ate the same food as me.”

Castillo said that a part of her wanted to be more Western than Filipino and that’s where her disconnect to the culture came from.

“My parents always wanted to raise me and my siblings as Filipinos, and keep us in that culture, because that’s everything that they knew,” she said. “I think my parents wanted to experience America, but not really root themselves in the American culture.”

Filipino Americans face a complex identity divide as some parents instill rich Filipino traditions to preserve their heritage while others choose a more Americanized upbringing, believing it offers their children a better chance for survival.

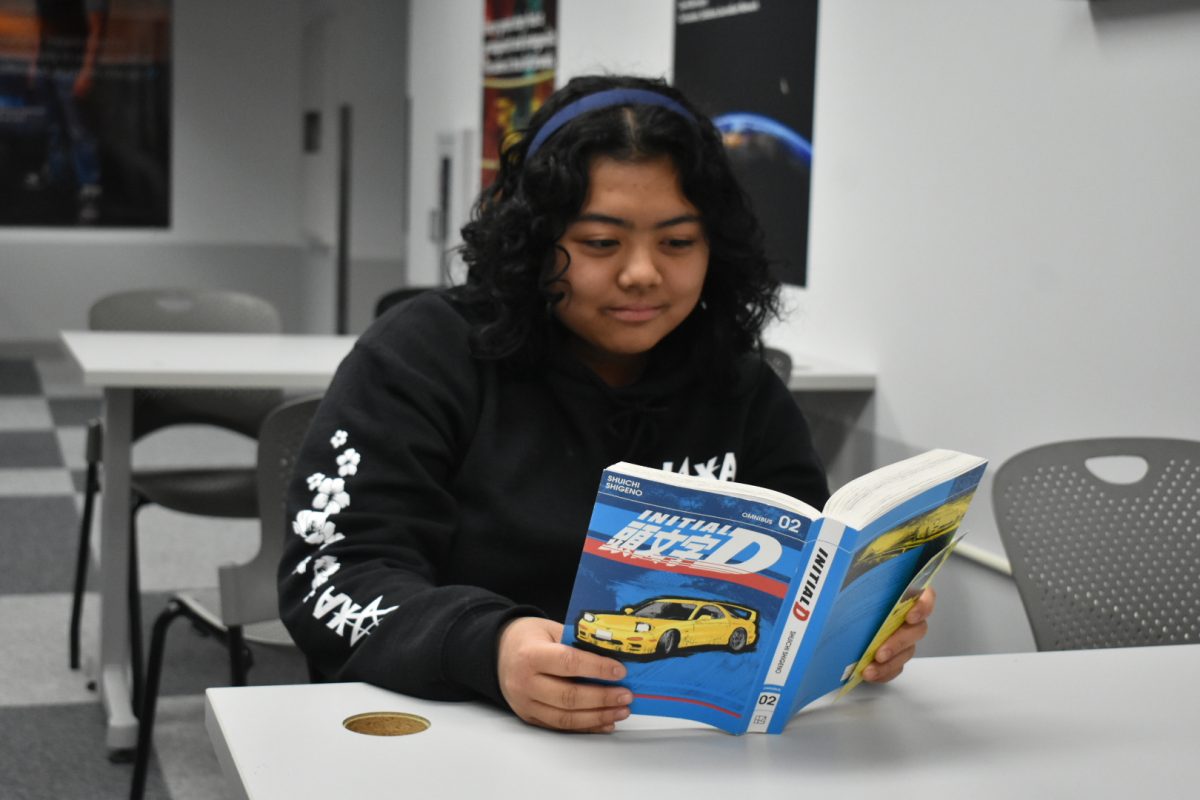

“I’m very immersed in Filipino culture, to the point where if I try to connect with a lot of other Filipino Americans, they can’t really relate,” De Ocampo said.

For sophomore acoustics major May Asuncion, her grandparents were very adamant on having them assimilate to American culture, but she understands why.

“They were raised in a very poor area, so they were like, ‘oh, going to America is good. It’s gonna give you a better life,’” she said.

Asuncion said that she always tried to fit herself in somewhere she was able to, one of them was with the musician kids.

“I lived in a very homogenous town, and there were three Filipinos, one was me, one was my younger sister and one was my cousin. So it was a little lonely,” she said. “I tried to change myself in order to fit in.”

Asuncion said that she could have done so much more to be in touch with her heritage, but she “was very obsessed with being the right person for the people.”

First-year creative writing major TJ Hoyt’s upbringing revolved around the church because of his very Catholic Filipino mother.

“I am Filipino, and I always grew up in that culture, but when I went to school and stuff, I was very white passing, and it was really awkward at times because I would sometimes be classified into one category,” he said.

Hoyt recalls having to fill out a form and there was no biracial option.

“I was like, ‘Hey, what do I put?’ and he went, ‘You have to pick one.’ And I was like, ‘That doesn’t really work out. I can’t do that.'”

Hoyt said that being a Filipino in the U.S. means having to seek out that community and search out for other Filipinos.

Growing up in a predominantly white suburb, fashion merchandising alum Isabella Pacheco was often the one of only a few Asian kids in her class.

It didn’t bother her initially, but when one of her titos asked her if it bothered her that she didn’t look like any of her friends, it opened her eyes to “how much I was ‘othered’ in subtle ways.”

Pacheco said that she often felt caught between two worlds, feeling “not Filipino enough” in the Philippines and “not American enough” in the U.S.

“At school, I’d bring Filipino lunches that would get strange looks and comments, while back in the Philippines, family would chide me for not being fluent in Tagalog, calling me a ‘half-Filipino’ or not ‘real,’” she said.

Having both multigenerational households on both her parent’s sides has helped music business alum Jaeya Bayani remain rooted in her Filipino heritage as a Filipino American.

“We reflect the experience of the Filipino American, in that, we’ve taken from what we’ve been given to create a culture that is inherently unique to our context, but always rooted back home,” said Bayani, who graduated in 2024.

Bayani said that on a socioeconomic level, “the Filipino culture, the Filipino American culture, and the Filipino diasporic culture, and the American culture are all on their own entities that happen to intersect.”

Bayani hopes that people understand that the Filipino culture and experience is a different entity from the Filipino American culture and experience.

“One of the most heartwarming things to see is the exploration of identity be way more open that it was in high school; and finally not hearing that weird comeback in high school that being hella Filipino was ‘putting yourself in a box’ when we’re already put in a separate box when we list our ethnicity anywhere,” Bayani said.

Castillo also emphasized that all Filipino Americans, regardless of how they were raised, are still Filipino.

“I think that’s the important part, to remember, regardless of where we came from, regardless of how we ended up, at the end of the day, we’re always gonna be Filipino,” she said. “I take pride and ownership of our culture and our history, and it’s important that we acknowledge where we came from to appreciate where we are now.”

Copy edited by Trinity Balboa