MENTAL HEALTH ISSUE

Students coming from strict religious or cultural backgrounds can face both freedom and internal conflict when exploring their sexuality or identity if these topics were not discussed at home.

Sometimes, they just need a place to talk.

Several community centers in Chicago provide that safe space to deal with the mental and physical impact of confronting their backgrounds as they create their own definition of who they are.

What they did:

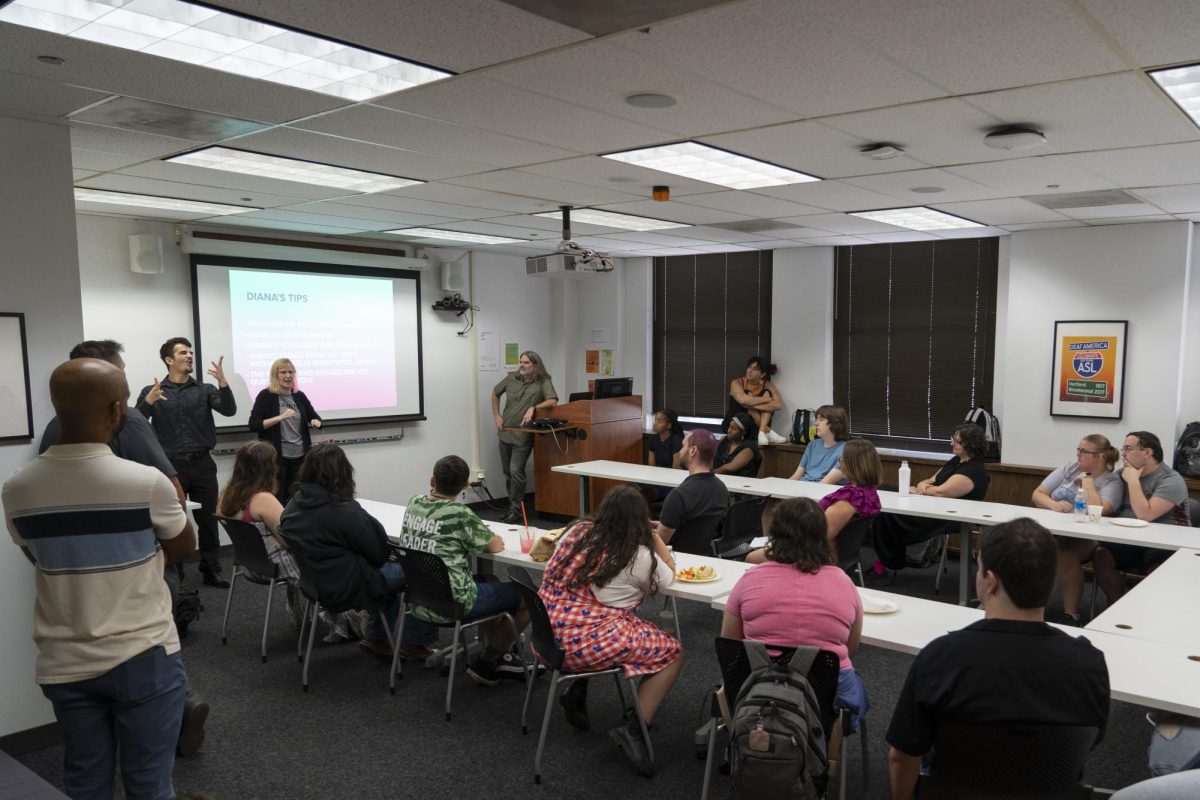

The Center on Halsted, formerly known as Horizons Community Services, first opened in 1973 in Chicago, and is now the largest LGBTQ+ social service agency in the Midwest. According to Kathryn Brown, an advocate clinician for the Anti-Violence Project and behavioral health departments with the center, a variety of resources are offered, one of which is a religious trauma group that Brown runs.

“We center everything around the lens of gender expression, sexuality and how those can be impacted or impaired,” Brown said.

They said the support group serves as a space for members of the community who have endured religious trauma. Members can talk about their experiences and learn about how it has affected their mental health, gender and sexual identities.

Religious trauma is defined as a religious experience that has been stressful, degrading, dangerous, abusive or damaging.

Support from community donations and grant coverage allows the center to continue providing other resources that are open every day. With their main goal of providing accessible support to LGBTQ+ individuals’ mental health support, they also provide other types of therapy groups, youth and family services, training to students looking to become therapists and more.

“What sets us apart is offering that accessible and comprehensive mental health care,” they said.

The center expanded its services to the South Side, opening The Center on Cottage Grove in 2022, along with a youth and family services program.

What they found:

According to Brown, religious trauma’s impact can be broken down into four main categories: cognitive, emotional, physical and social. Across the board, symptoms such as anxiety, depression, identity confusion, fear, excessive shame and guilt are seen among those who come into the center for help.

“Of course, that’s not to say that is all due to religion,” they said. “There’s a lot of other factors that play a part, but those are some of the more common ones that we see talked about, specifically in the religious trauma group.”

By the numbers:

According to their fact sheet, their $7.1 million in revenue has allowed them to continue providing services to support the center’s attendees, such as the 1,796 clients that have used its behavioral health services.

These services include therapy sessions for families, relationships and individuals in the LGBTQ+ community, along with the religious trauma group.

Between the lines:

To continue to allow the community members to have their voices heard, The Center on Halsted hosts events like Community Listening Session, Gay Men’s Book Club and “The L Lounge,” a lesbian/queer social support group in which members include cisgender, transgender and non-binary women. They are able to build community and obtain a safe space to come out and be themselves.

They also offer resources such as HIV/AIDS and STD testing, and LGBTQ+ affirming youth groups. The center is open every day from 8 a.m. to 9 p.m. to the public and all ages.

What students are saying:

After McKay Davis, a marketing senior, came out as bisexual at age 15, she watched her mom walk out of the room without saying a word in response. Davis went to find her mother in the living room to continue the conversation, only to find that her mother didn’t understand.

According to Davis, her mom said it would be easier if she could just choose between being gay, or even easier, being straight.

As the cultural and religious backgrounds of students at Columbia influence their identities to this day, many take the initiative to break the norms and create their own definitions of what it means to be connected to their roots.

Though Davis described this moment as “heartbreaking,” she appreciates how far her family has come to accept her identity and understands their perspective, coming from a Japanese and Polish-Catholic background. In Davis’s experience, coming from an immigrant family impacts the liberty to talk about sexuality and gender identity at home.

“I can’t tell you how many times people have told me ‘You don’t have to hide; go home and tell your family, go by the pronouns that you feel most comfortable with,’” she said. “When they don’t understand that it would break a lot of my family’s heart to say that.”

As talk of sexual identity is kept to a minimum at home, a similar attitude was taken to sexual education, Davis said.

“My mom was actually a really rare presence,” she said. “We didn’t take sex ed, we went to a private Catholic school, so just nobody knew and was in complete ignorance.”

Sumana Syed, senior film and television major, also felt in the dark while learning to adapt to the changes of puberty.

Syed, who is the president of the Muslim Student Association, said her grandma passed on cultural and religious customs by telling her that a woman’s period was not to be talked about, especially with the men in the family.

“I remember the first time where my mom and my sister were downtown, and I got my period, and I needed to get pads,” Syed said. “But I was young and I couldn’t just go and get them myself, so I had to just tell my dad … I remember it was such a nerve-wracking thing for me, to gather the courage to tell him, but ultimately, I was just like, that was something that I need[ed] to do for me.”

While Islam has religious customs of prohibiting premarital sex, rules for who women and men can marry and gender roles within the marriage, Syed feels for Muslims of different identities that have been stigmatized for practicing outside of the norms.

“Ultimately, Muslims should be open to people from all backgrounds wanting to be in the sun; it doesn’t matter if you’re a part of the LGBTQ+ community, or if you’re not Arab, or not Indian, everyone should be welcome,” Syed said.

Creating a personal definition of a relationship to one’s own religion, even if it means breaking the norm, is all too familiar to William Molina, first-year film and television major.

After a few years of fearing rejection from his Mexican-Catholic family and those at his church, Molina came out to his parents as gay his sophomore year of high school. Though he has faced some judgment within his church since, he’s gained the confidence to attend mass comfortably in his own skin, and accepted to learn the word of God alongside his peers, with the support of his parents.

“There’s a lot of tension when it comes to being gay in the Catholic community,” he said. “Whenever I go to church with nails or makeup on, I get weird looks, or people ask me, ‘Why do you still believe in this and like, still follow these things?’ But God, it’s just me and him. And it’s my personal choice, so I shouldn’t be affected by what anybody else thinks.”

Copy edited by Vanessa Orozco

Resumen en Español

Los antecedentes de crianza, cultura y religión afectan la sexualidad e identidad sexual, para muchos jóvenes cuando vuelven independientes. El Centro en Halsted ofrece servicios para jóvenes y familias, entrenamiento para estudiantes que están estudiando ser terapeutas y grupos de apoyo para la comunidad LGBTQ+. Kathryn Brown, asociada clínica del proyecto contra la violencia, y departamento de salud conductual al centro, dirige un grupo de trauma religioso. El grupo ayuda a los de la comunidad LGBTQ+ que sufren de los síntomas de ansiedad, depresión, confusión de identidad, miedo y de la vergüenza excesiva, por el choque entre quienes son, y las normas de su religión y cultura. Recursos como estos tienen la meta de ayudar a jóvenes como los estudiantes de Columbia, quienes han experimentado los desafíos de crear sus propias definiciones de lo que significa estar conectado con sus raíces.

Resumen en Español por Sofía Oyarzún