Part One: CFAC candidates on teaching at Columbia

November 27, 2019

Editor’s Note: This is part one of a three-part series introducing the part-time faculty members running for leadership positions for CFAC in the December election. Part two will address the candidates’ ideas for the union, if elected; part three will address allegations each slate is facing from the opposition.

As members of Columbia’s part-time faculty union gear up to cast their votes in next month’s election, both slates running for the top leadership positions profess to have two of the same goals: making Columbia the best institution it can be and making sure students are getting the best education possible.

The Chronicle sat down with each of the candidates on the incumbent Standing United and the challenging Reform CFAC slates, who are running for Steering Committee positions in the CFAC election, to discuss their journeys to becoming professors and what makes teaching at Columbia unique. Votes are scheduled to be tallied and announced on Dec. 9.

STANDING UNITED SLATE

(From left) President Diana Vallera, Vice President Andrea J. Dymond, Secretary Lisa Formosa-Parmigiano and Treasurer Susan Van Veen.

The Standing United slate comprises current Steering Committee members running for reelection, including: Diana Vallera, adjunct professor in the Photography Department, for president; Andrea J. Dymond, an adjunct professor in the Theatre Department for vice president; Lisa Formosa-Parmigiano, an adjunct professor in the Cinema and Television Arts Department, for secretary; and Susan Van Veen, an adjunct professor in the Business and Entrepreneurship Department, for treasurer.

On Columbia

Faced with the growing limitations of higher education, Vallera entered the teaching profession with a background in fine arts photography. Working at Columbia, she loved the open access given to students to pursue an education and the opportunity to be a female role model for her students.

“I can’t think of any other profession that brings so much value and reward,” Vallera said. “In this country, it’s not a profession that is valued, and it should be one of the most valued professions.”

Van Veen had teaching “in [her] bones ” as she grew up with her father, an educator, and said she later came to Columbia because she had great admiration for the school. Even after being director of education with the Chicago Street Theatre, Dymond said she could not imagine being a teacher. But during her 12 years at Columbia, Dymond discovered a passion for teaching, saying it was quite different from what she expected as her students became collaborators in the industry.

Formosa-Parmigiano decided to become a teacher when she had an “earth-shattering experience” in which a fellow classmate broke down and she became inspired to help future students of her own.

“There’s nothing more rewarding to me than being in the classroom teaching,” Formosa-Parmigiano said. “The day I stop learning in the classroom while I’m teaching is probably when I won’t do it anymore.”

Having been at Columbia since the ‘90s, Formosa-Parmigiano said the expansion of the college has not been good for it with regard to higher expenses and a decreased quality of the curriculum, although the heart of it as a “commune with a computer” is still in place.

Pointing to a Chronicle article on expected enrollment for Fall 2020, Van Veen said the school is focused on profit, which is built “on the backs of our students and on the backs of our faculty.”

REFORM CFAC SLATE

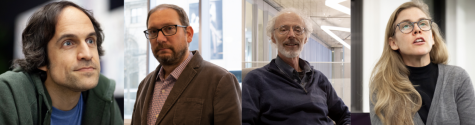

(From left) Derek Fawcett, Jason Betke, Christopher Thale and Colleen Plumb.

The Reform CFAC slate is comprised of Derek Fawcett, an adjunct professor in the Music Department, for president; Jason Betke, an adjunct professor in the Cinema and Television Arts Department, for vice president; Christopher Thale, an adjunct professor in the Humanities, History and Social Sciences Department, for secretary; and Colleen Plumb, an adjunct professor in the Photography Department, for treasurer.

On Columbia

None of the Reform adjuncts planned to become professors.

Fawcett had been performing jazz around the city when “Columbia came calling.” But once at the college, he got to experience the joys of teaching through student interaction and witnessing their musical breakthroughs.

“It’s easy to forget, in the business of all of it, how noble a profession this is,” Fawcett said. “In the haze of all of the things that happen in the rat race of the semester, you’re just going about doing your thing, and you do something and you get a message from a student [saying], ‘I just want to thank you for that because it really mattered.’”

Betke also “fell into teaching” when he started instructing courses as a graduate student at Columbia in the ’90s. As a professor in the Cinema and Television Arts Department, he always loved movies as a kid, especially classic Hollywood films like the 1942 romance “Casablanca.”

Before becoming a history professor, specializing in urban and working-class history, Thale was a sheet metal worker. One day, he signed up for a course and eventually was sent applications for graduate school.

As a fine art photographer with a book and numerous exhibitions under her belt, Plumb said becoming a professor was important to her work. She said being an artist can be isolating, and working at Columbia has given her a community.

“It’s really fulfilling to share my experience with students,” Plumb said. “We want the union to be this invisible force that will exist to benefit the students.”