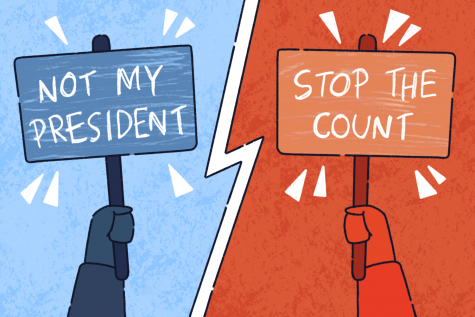

Opinion: Saying ‘Not My President’ is not the same as ‘Stop the Count’

December 8, 2020

The window to legally dispute the results of the 2020 election is coming to an end on “safe harbor” day, Tuesday, Dec. 8, when all state-level election challenges are supposed to be completed, according to federal law as explained in a New York Times article.

Next week on Monday, Dec. 14, the Electoral College is scheduled to officially cast its votes and declare an official victor.

As mail-in votes continued trickling in days after the election on Nov. 3, President Donald Trump took to Twitter to demand officials “STOP THE COUNT.”

More than a month later, he and his followers still dispute President-elect Joe Biden’s victory, and I am reminded of the rejection of Trump in 2016 with the slogan “Not My President.”

After presidential candidate Hillary Clinton lost the election to Trump despite winning the popular vote, many Democrats were upset the Electoral College allowed a president to be elected without winning the overall vote of the American people. Trump was “Not My President” to a large portion of the population.

Although both phrases are essentially rejections of a president-elect on the surface, they are not entirely the same.

Martha Ackelsberg, the William R. Kenan Jr. professor emerita of government and professor emerita of the study of women and gender at Smith College, said there is a false equivalence of “Not My President” and “Stop the Count.”

“When people said ‘Not my president,’ they meant ‘I don’t like this man. He is not representing me,’” Ackelsberg said. “That’s not the same as saying ‘This election did not take place,’ or ‘This election was fraudulent.’”

After Trump won the Electoral College vote and the presidential election in 2016, people who felt their vote did not count took a look at the system created as a compromise between a presidential election decided by Congress and one by the people.

But following Trump’s loss of both the popular and Electoral College votes, it was echoed by Trump and his supporters that the problem was with the people and their “fraudulent” votes, rather than the system itself.

The protests in 2016 and 2020 played out differently as well. Proponents of “Not My President” protested, admittedly violently sometimes, at government buildings and Trump Towers, while those shouting “Stop the Count” swarmed voting centers where recounts were taking place in an attempt to intimidate election workers.

As Acklesberg said, the two slogans are not equivalent. Each has the surface layer of rejecting a president, but their cores stem from two different places—one of frustration with an outdated system and one of a belief in unproven widespread voter fraud.

However, Acklesberg said democracy is about the resolution of differences through peaceful communication, debate and voting, and if people do not agree on basic facts, democracy cannot function.

If we were to start throwing out votes because the president made claims on social media that they are fraudulent, we would be accepting a leadership where those in power do not uplift multiple political voices.

In future elections, we must remember to consider what we are fighting for. Are we protesting a system that does not serve its people, or are we trying to abuse a system for our own gain?

Public political dissent is a tool of democracy—so we need to use it wisely for the good of our neighbors, not to serve leaders who benefit only a privileged few.