MENTAL HEALTH ISSUE

Since 2020, students have been thrust into experimenting with new learning models following the sudden shift to online learning brought on by COVID-19. This caused workloads to balloon for students and faculty alike.

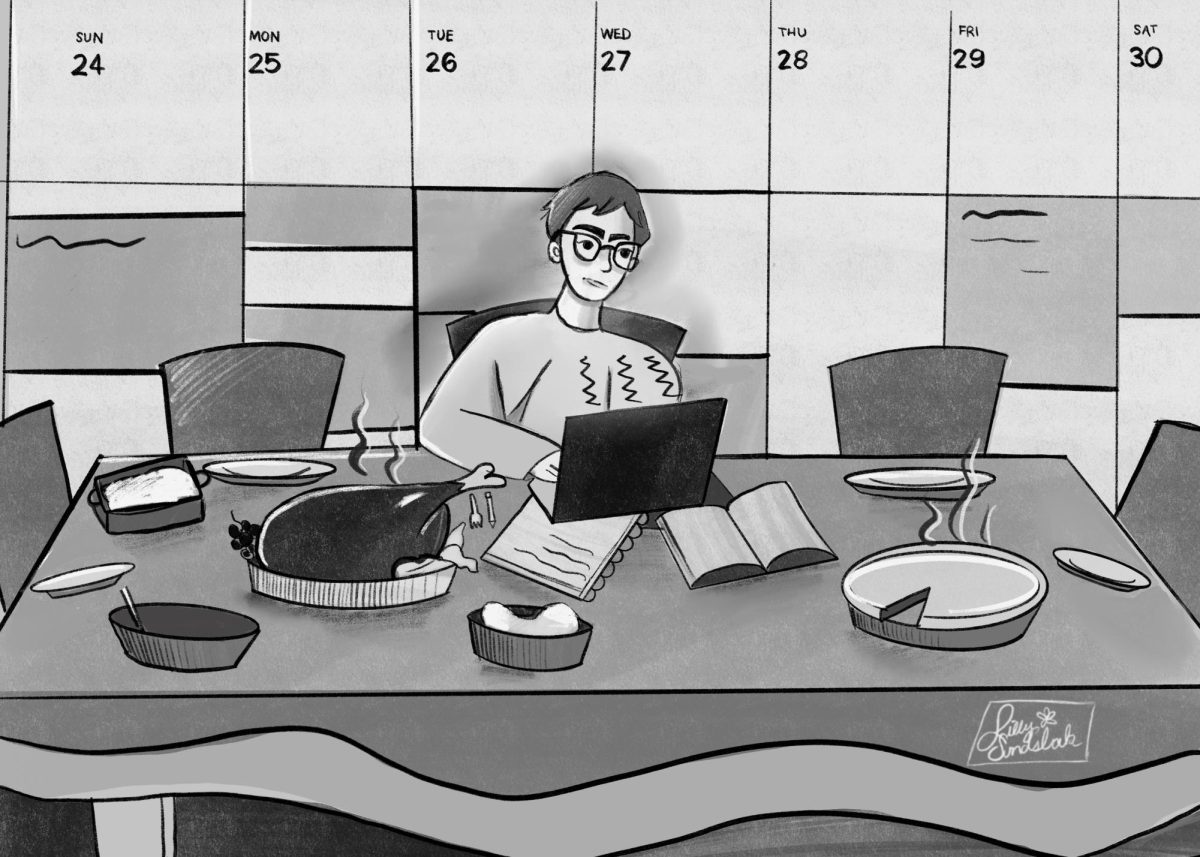

In the shift to “Zoom University,” as it’s been dubbed by students nationwide, academic workloads brought on new expectations that students need to be constantly accessible to classmates and professors while keeping track of each individual professor’s method to structure their course materials online.

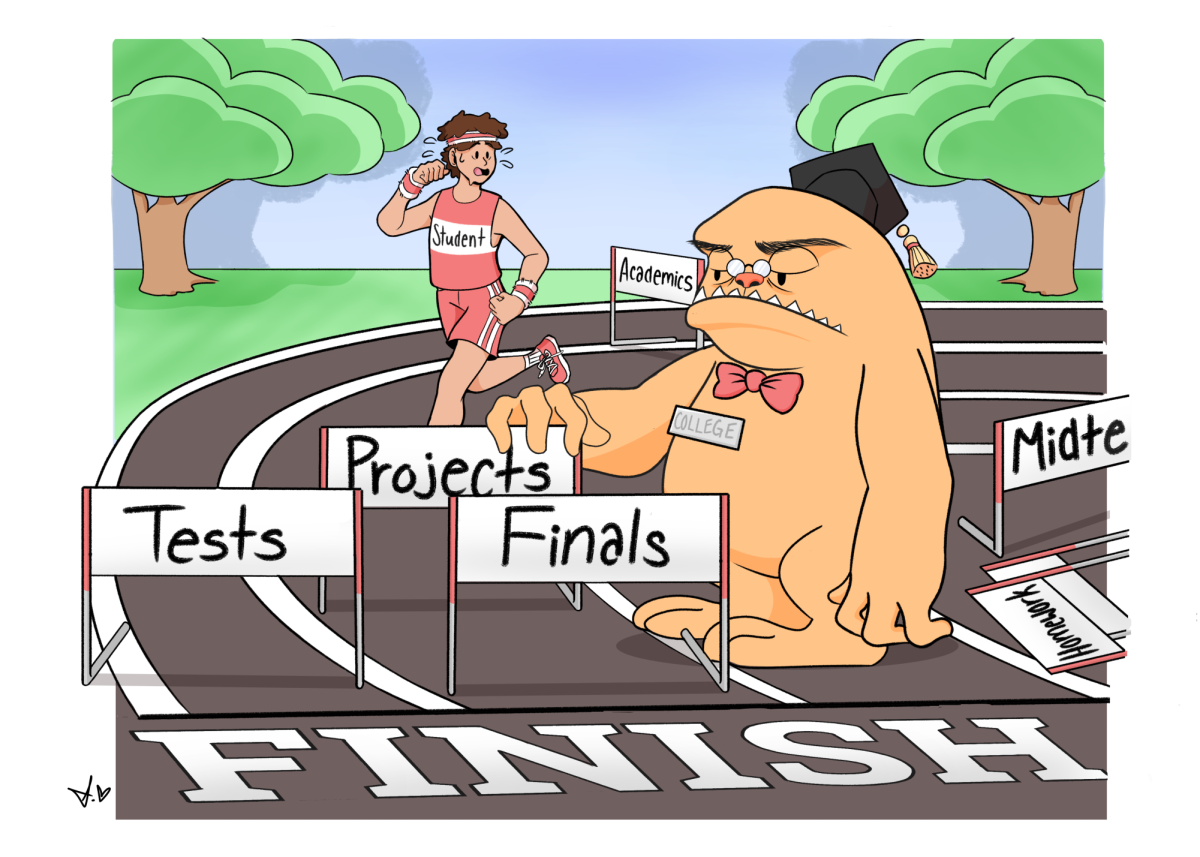

At many schools, students are recommended to spend three hours studying for every hour spent in a classroom – a formula that means students with a 16-credit hour workload should be spending 48 hours each week just to keep up with classwork. With this recommended time frame, students who work full-time might be spending more than 100 hours each week on classes, employment and studying out of a total 168 hours in a week, a staggering figure even before adding on basic human necessities such as sleep, meals and personal hygiene.

In context, these factors point to one conclusion: students need to be thrown a lifeline that reduces workloads to a reasonable level as many of them put in weekly hours that would be eligible for overtime if being a “student” was a paid position under federal labor laws.

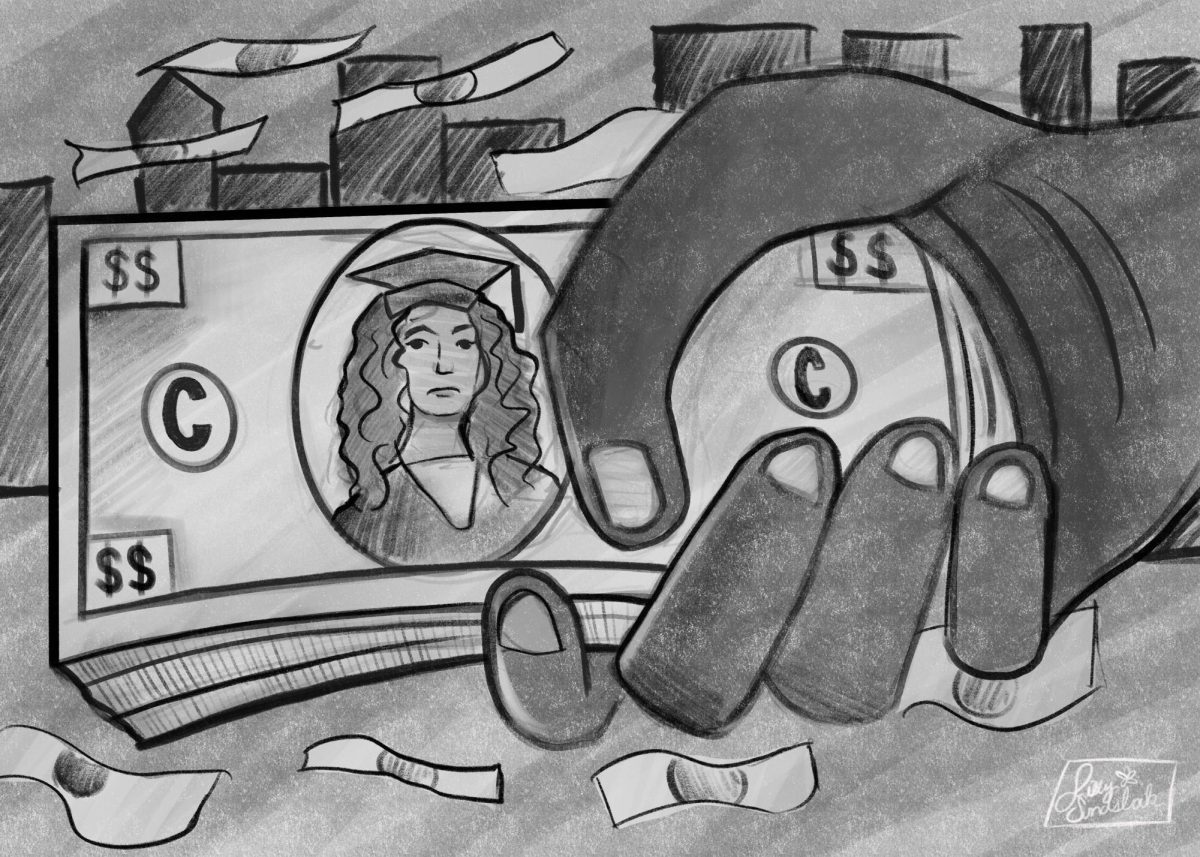

With this staggering workload, it’s no small stretch to imagine that a fair chunk of college students, after spending on average four years balancing this workload, reach graduation and are completely burned out, desperately needing a break that will never come in this economy that pushes for higher profits for less cost, leading to workers spending less time relaxing when needed.

While students currently in school are some of the most capable in history, with the help of wide internet access, we’re also human, facing some of the worst disasters ever seen, including climate change, inflation and job offers that dry up as quickly as they’re posted.

With these major hurdles to overcome, there are immediate changes which colleges can undertake to ease the burden placed on students with little impact on educational outcomes.

Professors should consider their class workload and reduce required assignments such as readings, discussion posts and quizzes, especially in non-major classes. In this example, students would have more flexibility to spend their time and effort on classes within their major instead of being forced to play assignment roulette with their limited free time.

Within my experience thus far at Columbia, where I’ve spent the last two years, failing to balance working full-time as a freelance photojournalist and being a full-time student, being thrown a lifeline by professors could have looked even as simple as being flexible with deadlines. I live in a career field where deadlines are as strict as a concrete wall and missing even one deadline can have enormous consequences.

Due to that, I’ve often had to prioritize professional work over academics in order to protect future assignments, which are critical to paying the bills. However, if I were allowed to be flexible on academic deadlines without as much penalty, I’d be more engaged with ensuring work is turned in, even if it’s a few days behind my peers.

There are other Columbia students who are similarly drowning under academic and professional pressures, in need of a lifeline. Columbia should strongly encourage professors and instructors to make immediate changes to a more flexible deadline policy to ensure that every student has the best chance at graduating, regardless of any challenges they face.

Trent Sprague is a photojournalism major from Prospect Heights, Illinois.

Copy edited by Patience Hurston