In the early years of the modern Columbia (1960s to present) there came a time that the college was in an acute financial crisis and unable to pay its bills. Jacob Caref, the chief custodian, cashed in his life insurance policy and loaned the funds to the college to bridge the gap between income and expenses. Yes, he was paid back.

Shortly after my return to Columbia in 1971 to serve as dean of the college, there came another time when Columbia did not have enough available funds to meet payroll. President Mike Alexandroff asked (and I mean asked not demanded) the college’s top administrators if each of us would agree to defer receiving our salaries for two or three pay periods so faculty, including part-timers, and staff could receive their checks. All administrators agreed. After all, we were a community.

In 1984 my two-year-old daughter was diagnosed as having a cyst in the middle of her brain that required brain surgery. As you can well imagine, both my wife and I were in a state of shell shock. Word got back to Mike of the crisis my family was facing. He called me to come to his office. “Lou,” he said, “you’ve got enough on your plate right now and don’t need to worry how you are going to pay for hospitalization and surgery. Get the best care for her. The college will cover the cost.”

Columbia has come a long distance from those days. For the better in many ways. And, unfortunately, also for the worse in many ways. Most prominently, there no longer exists a Columbia community with all parties basing their actions on what best serves the common good — administrators, all faculty, students, staff and building/maintenance crew.

In 1978, Columbia College awarded labor and civil rights activist Addie Wyatt an honorary degree. In her words: “I didn’t know what the union was. But I know that I needed help and here was the place that I could get that help. I knew that I wanted to help other workers, and I found out that I could help them by joining with them and making the union strong and powerful enough to bring about change.”

If she were still alive and returned to Columbia, she would be both shell shocked and dismayed that there are those among the privileged class — well paid full-time faculty with health insurance — who are crossing picket lines to take over the classes of part-time faculty striking to get their fair share of the financial and other benefits available to college employees.

My mother, an uneducated immigrant woman, was able to earn a living wage due to the organizing efforts of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union. She became a floor leader and had harsh but truthful words to describe those who crossed pickets’ lines to undermine the struggle for workers seeking their just due. Not just strikebreaker but scab.

Such strikes have also occurred within institutions of higher education, including City Colleges of Chicago, where the overwhelming number of students are on financial aid. Realizing the deleterious effects of the strikes on students, virtually all institutions have had the strikes settled in time before putting students at financial or academic risk.

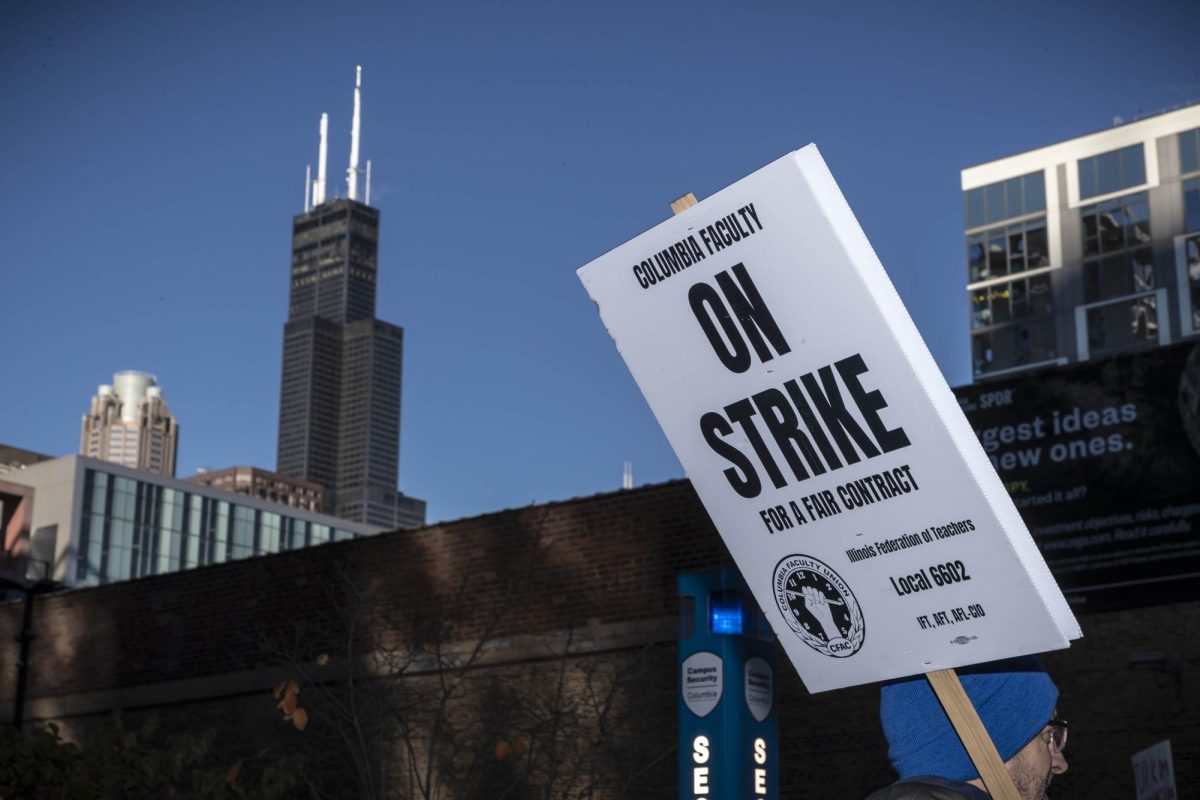

The Columbia administration has decided to take a different approach: break the strike and thereby break the union so it can tell the part-timers, take our offer or quit Columbia. By utilizing full-time faculty to teach class otherwise taught by part-timers and by stressing the effects on students’ financial aid and graduation status, it believes that it will prevail. And should the administration prevail, the next step will be to increase faculty teaching loads and advising students.

As for those full-timers who believe that by taking over the classes of part-timers, they are serving the best interest of students and the college as a whole, I suggest that at least they donate a portion of their salaries to part-time colleagues in their respective departments during the course of the strike. However, by taking over classes, the best interests of colleague part-timers are not being served and that of the administration.

Based on what has worked at other institutions dealing with a strike by faculty, what needs to be done to get administrators to sit down with part-time union reps and come up with serious offers that hopefully part-timers would agree to, is for full-time faculty to refuse to take over any of the part-timers’ classes, as I have been led to understand some faculty members have done, and for students to organize and put heavy-duty pressure on both the administration and part-timers to come to an agreement.

Louis Silverstein

Distinguished Associate Professor of Humanities

This op-ed has been updated.