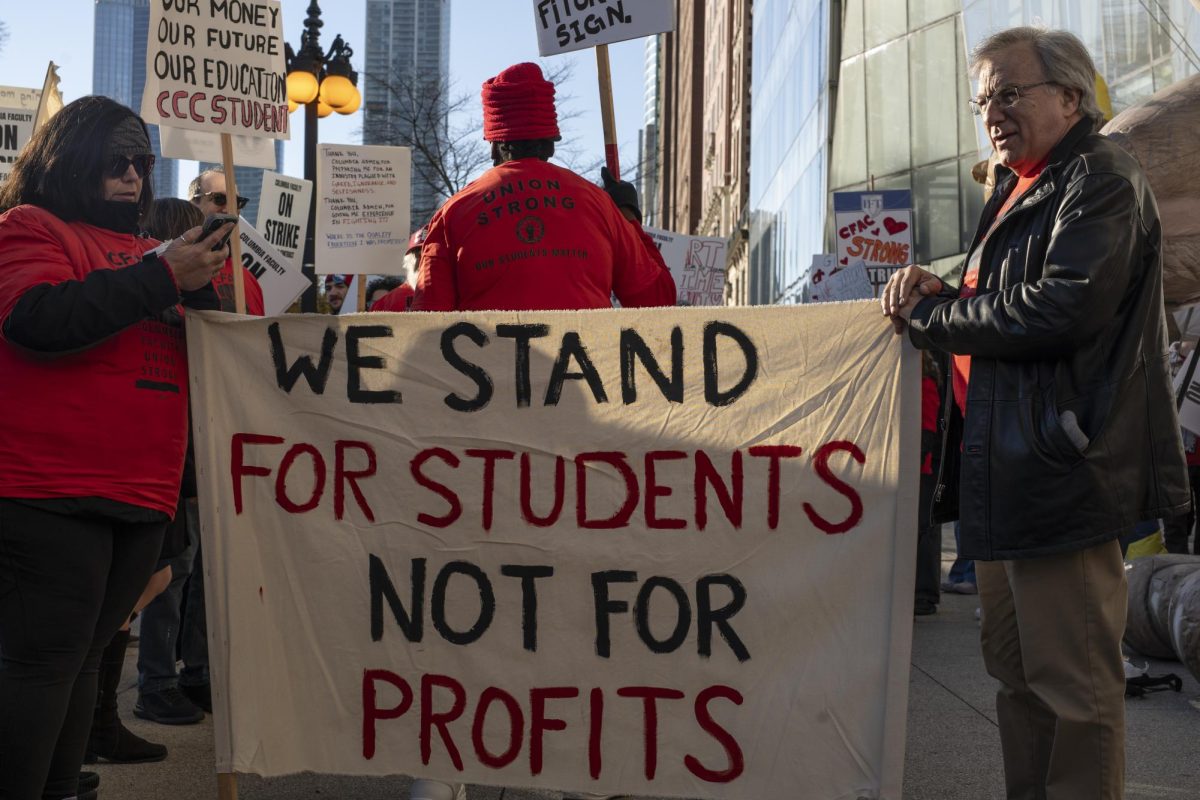

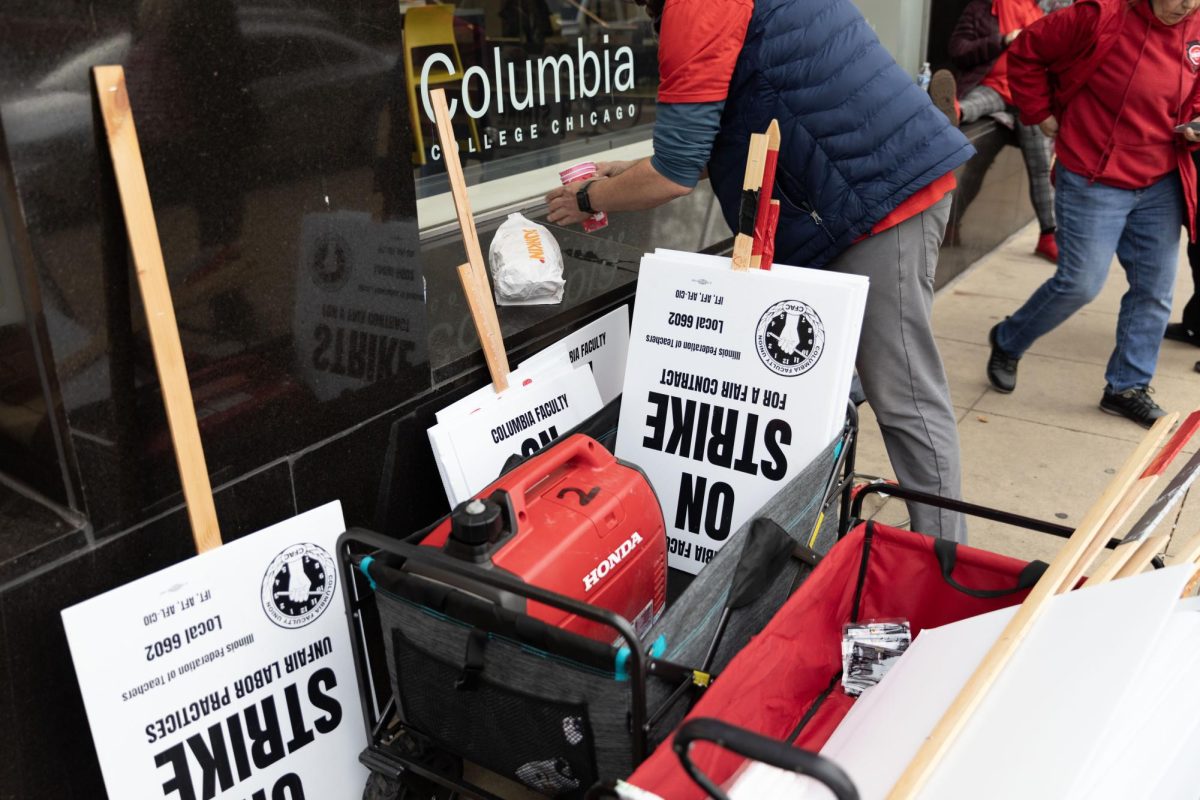

As the college heads into the third week of the part-time faculty union strike, students and faculty are seeing similarities between this and when COVID-19 unexpectedly shut down the city. In March 2020, Columbia paused classes for three weeks to shift them online.

Some classes have not met since the strike began on Monday, Oct. 30, while others have only met on Zoom.

Sophomore art history major Alyssa Vanderveen said four of her five classes are not meeting due to the strike. With the majority of her classes interrupted, she feels unsure how to proceed.

“You don’t know what work you should be doing because you’re not in class to figure out where you’re supposed to be,” Vanderveen said.

Not only is she concerned about the impact the break will have on her academic progress, but she also misses the normalcy of her schedule.

“It’s hard not having your routine,” she said. “I only have one class, and I’m from Michigan so I can’t just go home all of the time. I’d love to just go home, but I just sit in my dorm.”

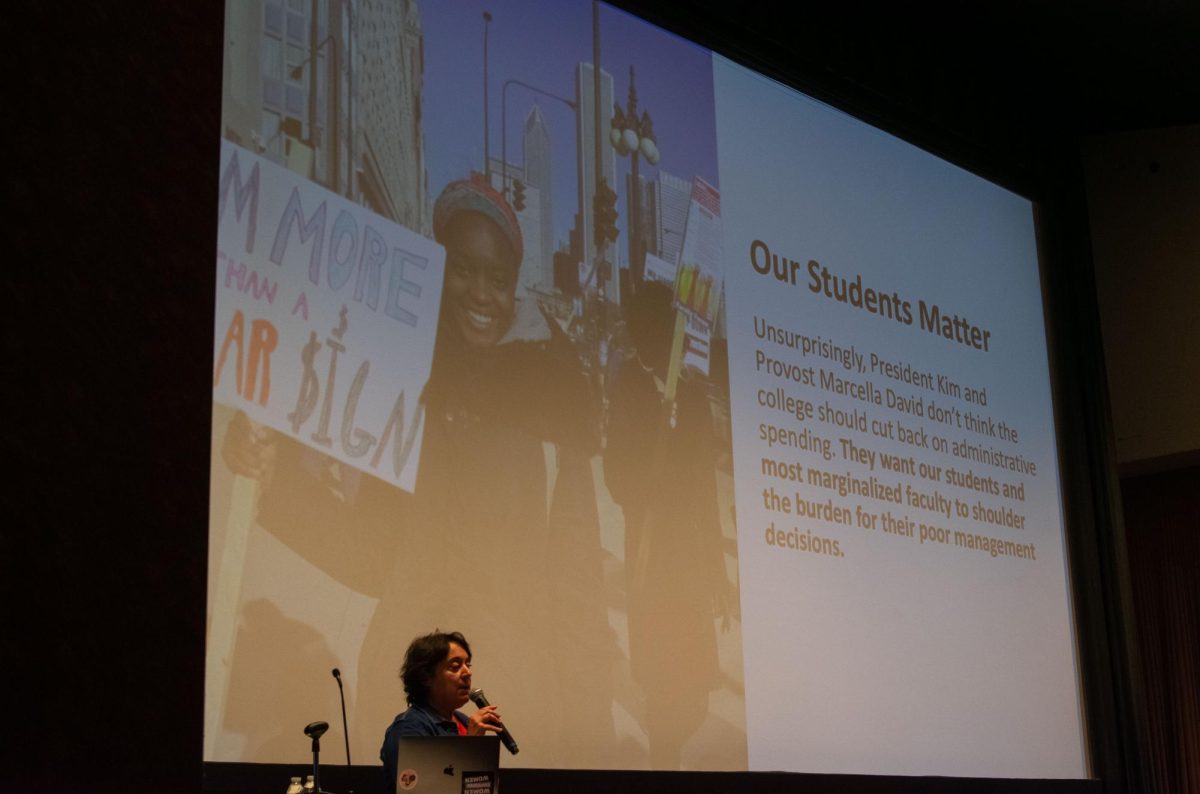

Senior Vice President and Provost Marcella David said she recognizes the similarities between adaptations being made currently and the college’s strategies in Spring 2020 when COVID-19 first broke out.

“It’s an identical kind of process,” she said. “I am asking deans and chairs to think about ‘What does it mean to restart?’ ‘What are the challenges we might face in that?’”

David is focused on ensuring that the current learning loss will be taken into account and will not have a negative impact on students when classes resume.

“The first and last question is ‘How do we help students succeed?’” David said “That’s true for me, that’s true for the people who work in my office.”

Department chairs sent out emails to faculty members and part-time instructors over the weekend asking them to reevaluate learning outcomes and adjust courses based on time lost during the strike.

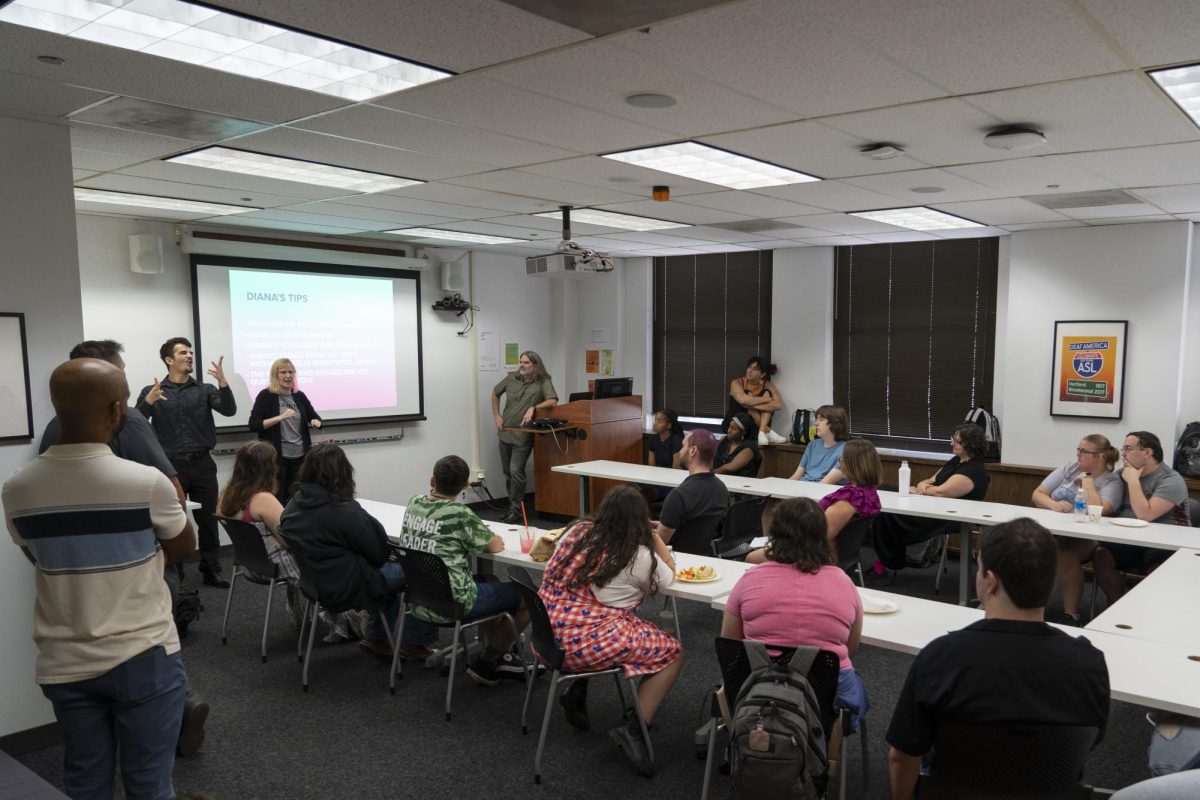

Ames Hawkins, a former associate provost for faculty research and development, was a part of the team that helped the college adapt to the disruption in learning in 2020. They see the COVID-19 disruptions as educational precedent for being flexible in instruction and education.

“In terms of the pedagogy, there’s something here to parallel,” Hawkins said, who is a professor in the English and Creative Writing Department. “We actually have some skills and some knowledge here that we can work with. We’re not in a ground zero situation.”

Where COVID-19 forced all courses to move online, the strike’s impact varies on a more case-by-case situation depending on the department and the instructor or faculty member teaching the class.

“The similarities have more to do with the fact that people have an idea of what they might do to strategize, to address whatever the gaps in learning that might have happened because of the strike,” Hawkins said.

The college has sought to assure students that the strike will not impact their ability to earn credits toward graduation. But students are still worried about whether their grade point averages will be impacted and whether their work before the strike started will be valued.

Conversations about waiving assignments during the striking period have circulated among students and faculty but that still risks the hard work students like Xitlaly Barajas have put in.

“It’s not that I’m mad that other students will get a pass, but it’s like, are all of their assignments going to get excused even though I had really good grades?” Barajas said, who is a junior transfer student and art history major in her first semester at Columbia.

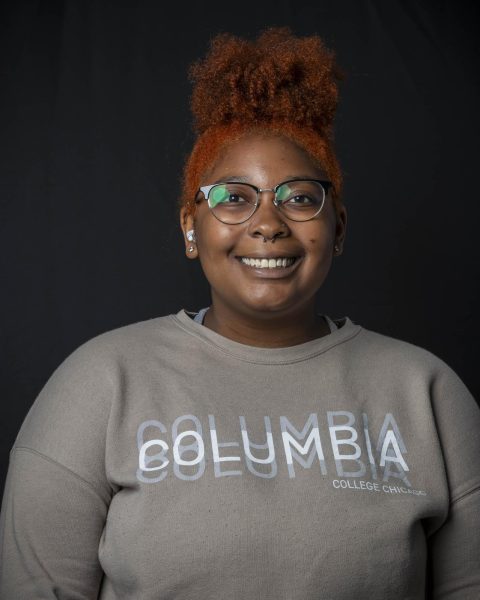

Sean Fontno, a senior graphic design major, was a first-year at Columbia when she was sent home from her dorm due to COVID-19 lockdowns. Three-and-a-half years later, she’s reminded of the uncertainty she faced during her first year at the college.

“I’m not trying to let this [strike] consume whatever I have going on, but I can’t help it,” she said. “I’m so stressed out.”

Fontno is currently only attending one of her three classes this semester due to the strike, and has been continuing to work on assignments in the event they will be due once classes resume.

“I don’t want anything to be pinned against me,” she said. “I don’t think it’s fair to either make us retake [classes] or stick with the grades we had before.”

Jovan Zepeda, a first-year film and television major, has also been trying to complete coursework in an effort to maintain his academic progress but feels a loss of connection in the absence of two of his classes.

“I’m not really learning the way I want to learn,” he said. “The whole point of going to college is to be there with your peers and be there with your teachers.”

Zepeda hopes to regain a sense of normalcy upon the return to the classroom.

“I know my teachers want to be back in a classroom teaching us,” he said. “You need to be in an environment with other people who are as passionate about art as you.”