Heart failure meets its match

The cyclin A2 gene may aid in heart tissue regeneration post-heart attack

March 3, 2014

Heart attack survivors may be able to better ward off heart failure with a new development in heart attack recovery treatment.

According to a study published Feb. 19 in Science Translational Medicine, a pig heart that was damaged by a heart attack was able to heal itself after being injected with cyclin A2 genes, which control cell division in tissue development. After one last preclinical trials, the treatment can begin testing on humans.

Gary Schaer, professor of medicine and director of cardiology research at Rush University Medical Center, is hopeful that this new development could be used to treat heart disease. He said heart disease is still the No. 1 killer in the United States, and heart failure continues to increase as the population ages.

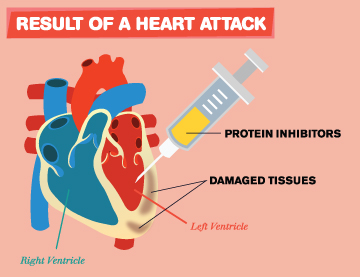

When a person experiences a heart attack, blood flow to the heart is obstructed, causing a portion of the muscle to die, according to Sandeep Nathan, associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago and director of interventional cardiology at the U of C Medical Center. Cardiomyocytes, heart muscle cells, do not have the capacity to divide and multiply in order to regenerate heart tissue, said Hina Chaudhry, director of cardiovascular regenerative medicine at the Ichan School of Medicine at Mount Sanai Hospital in New York.

Chaudhry began researching new treatments for heart disease 15 years ago. She said she thought the cyclin A2 gene could regulate cardiac muscle cell division because it is the only cell cycle gene in a mammal’s heart that becomes dormant after birth.

Testing of cyclin A2 on heart regeneration began in 2004 on genetically engineered mice designed to maintain the gene after birth, which allowed the cardiomyocytes to continue cell division, Chaudhry said.

“This was the first time that mitosis had been demonstrated in mammalian cardiomyocytes well after birth,” Chaudhry said.

A few years later, the team induced heart attacks in mice and injected their hearts with a virus containing cyclin A2 to see if the hearts could repair themselves, Chaudhry said. The mice hearts showed dramatic regeneration of heart tissue and cardiomyocyte mitosis, she said.

The final step was to administer this treatment to larger animals to determine if the results could be applied to humans, Chaudhry said. The team chose to use pigs because of the similarity in anatomy and physiology between pig and human hearts, she said. Chaudhry and her team used the same cyclin A2 virus on the pigs after inducing heart attacks. Again, the results showed regeneration of the damaged heart tissue, Chaudhry said.

The team also found complete cell division of the cardiomyocytes, forming two fully-functioning heart muscle cells by looking at tissue samples with cyclin A2 using time-lapse imaging, Chaudhry said. The cells were splitting into two daughter cells and the sarcomere—the muscle contracting unit in cardiac muscle cells—was preserved in each new cell.

“We’re really excited about the results we’ve seen and really hopeful that this is going to work for human patients,” Chaudhry said.

Current treatments for heart failure after a heart attack include medications that decrease the heart’s deficiency as a pump, Nathan said. Other therapies include short- and long-term heart pumps and, in severe cases, heart transplants, he said.

“The most important way to reduce the burden of heart failure is to provide as much blood flow to the heart muscle as possible,” Nathan said.

Overall, the current treatments are effective, Nathan said. But he said timing is also important, which is why the new treatment is important for heart attack sufferers. Chaudhry said her treatment showed heart regeneration within six weeks of the injection, which may be fast enough to prevent heart failure in humans.

“This is a promising leap in the direction of a novel therapeutic using a therapy model to simulate cardiac regeneration in damaged hearts,” said Scott Shapiro, associate professor of medicine at George Washington University Hospital and a member of the research team. “It may also be good for other types of damaged hearts, not just ones that have been affected by [a heart attack].”

Schaer predicted the treatment would need an additional 10 years of development before being introduced to the market. Chaudhry said the team is awaiting approval from the United States Food and Drug Administration to begin Investigational New Drug enabling studies before human trials begin

“Preclinical research like this is very exciting,” Schaer said. “It’s … unleashing some of the potential of the heart to repair itself.”