Sad music plucks spectrum of emotional notes

Sad music plucks spectrum of emotional notes

February 16, 2015

For all its heartrending shrewdness, Neil Young’s single “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” climbed to No. 33 on the U.S. Billboard Top 100 chart in 1970.

The contradictory notion of love being the solitary force responsible for heartbreak is paralleled in the way Young ekes out his lyrical nostalgia over what is an arguably upbeat and buoyant melody. Music listeners across the world turn to songs like this despite the music conjuring painful memories and stirring up sentiments usually thought to be undesirable.

Research published in the journal PLOS ONE on Oct. 20, 2014, used survey data collected from more than 700 study participants from different parts of the world in an attempt to pry apart the reasons why people return, time and again, to music that upsets them. While the researchers looked at broad differences between study participants from the Eastern and Western hemispheres, no significant disparities were found among their responses.

“We wanted to address the question of why people seek and appreciate sadness in music,” said Liila Taruffi, lead author of the paper and a Ph. D. candidate studying music psychology at Freie Universität Berlin. “It’s an unpleasant emotional state that we typically don’t want to have in our lives.”

In addition to personality questionnaires, the study included questions about how often participants listened to sad music, in what mood, the range of emotions they experienced when they did listen and the psychological rewards of sad music.

“People tend to engage in sad music when they are already in a sad mood—when they feel lonely or are experiencing some sort of romantic trouble,” Taruffi said. “In most cases, music seems to be really powerful in the regulation of negative mood or negative emotion.”

The results also reflected that listeners would sometimes use sad music as an empathic tool to make a connection or generate a space they can use to express and explore the negative emotion.

“Sad music is rewarding because it’s easier for people to engage in imagination, to fantasize about their emotions by following the music,” Taruffi said. “It has no real-life implications, nothing really bad is happening so people can experience the taste of sadness without any negative life consequence.”

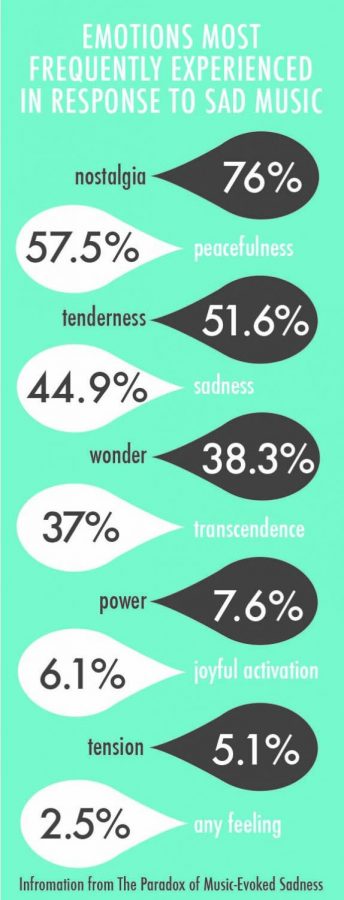

Researchers used the Geneva Emotional Music Scale model, which includes a range of emotions divided into nine categories, to measure the feelings most commonly evoked by sad music. Nostalgia—which is considered a mixed emotion featuring some pleasurable associations along with negative ones—received the largest number of ratings from participants, followed by peacefulness, tenderness and sadness.

“Nostalgia is linked to … appraisal of autobiographical memories,” Taruffi said. “Another reason people listen to sad music is to evoke memories of past personal events. A song might be able to remind them about their experiences, and it seems that sad music is really useful for these autobiographical reappraisal functions.”

According to Tuomas Eerola, a professor of music cognition at Durham University in the United Kingdom, studies show that people most commonly listen to music for functional reasons, such as cultivating desirable mental states or influencing changes in mood.

“It’s not that difficult to have thousands or even a quarter million musical examples,” Eerola said. “We have Last.fm or Spotify, a huge number of stimuli at our disposal, so we can map the features quite accurately to different emotions. [There is often] this kind of functional choosing of music for jogging or waking up—all of these very functional uses.”

Taruffi said another interesting finding was that differences in personality also modulated the way participants enjoyed sad music. The results showed that more empathetic individuals tend to enjoy sad music more when they are already feeling down, compared to the less empathetic. Similar conclusions were drawn about individuals who labeled themselves as emotionally unstable based on the questionnaires.

“This difference might be interpreted as emotional regulation strategies that specific groups of people are using to go through their everyday life,” Taruffi said. “One hypothesis is people with higher empathy and lower emotional stability might prefer to use sad music to regulate their negative emotions.”

Thalia Wheatley, associate professor of psychological and brain sciences at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, said that one of the most important aspects of the PLOS ONE paper is how it emphasizes the different ways listening to music can be rewarding.

Participants rated the lack of real-life implications to emotions evoked by melancholy music as the highest reward for listening. Wheatley said this reward could serve a social function as well as a personal one, enabling listeners to figuratively try on different emotions.

“By listening to music we can experience an ‘as if’ emotion in three minutes and we’re out,” Wheatley said. “I think it serves this very important social tuning function. It’s almost like social homework for the brain. We tune ourselves by listening to this and experiencing the depths of this kind of emotion in ways that are safe.”