‘What’s The Deal With’ Pop Art?

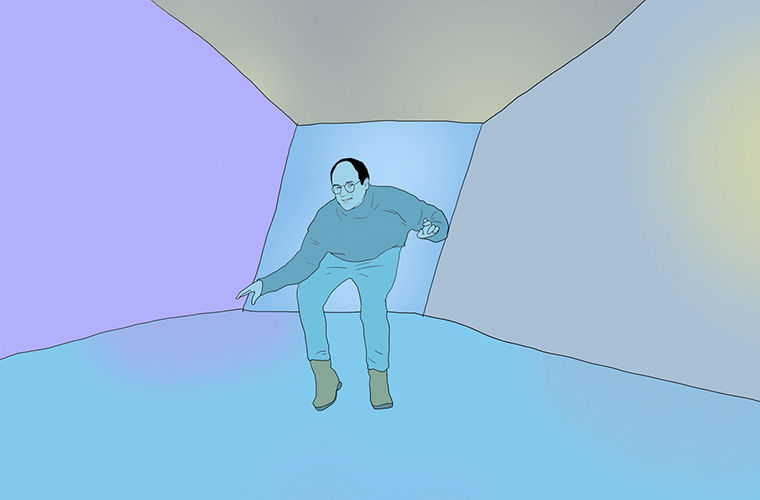

“Georgey Hotline Bling”

February 1, 2016

Throughout the last 27 years, Bart Simpson has been many things. He was an Academy Award winner, boy-band sensation and even somehow managed to stay 10 years old the entire time.

However, he was recently able to add another title to his already high-profile resume—a fine art subject.

The iconoclastic cartoon character is part of a growing pop art trend in which fine artists and commercial illustrators repurpose well-known figures—from “Adventure Time” characters to “Zoolander” and anything in between—to create works of art with contemporary references and cultural icons meaningful to millennials.

This new form of pop art builds upon the aesthetic that guided the first wave of pop artists in the ‘60s like Andy Warhol and the neo-pop artists in the ‘80s like Jeff Koons—taking everyday objects and placing them in a new context.

In place of Warhol’s silk-screens of comic detective Dick Tracy, artists are using different references, such as a Bart Simpson and Marty McFly mashup and George Costanza from “Seinfeld” doing Drake’s “Hotline Bling” dance. Many may have drawn inspiration from the 15-year-old Bootleg Bart phenomenon in which Matt Groening’s character turns up in unexpected places, such as playing for the Chicago Bulls or marching off to Iraq.

While tourists still scoop up these images on T-shirts in New York City’s Chinatown amid faux designer handbags, the gallery world is also taking notice of pop art by staging shows in London, Paris and Los Angeles, greeted by enthusiastic audiences.

Gallery 1988, a Los Angeles-based art gallery run by Jensen Karp, specializes in this genre. Eric Price, a sculptor who has had several shows at Gallery 1988 featuring his mask-like effigies of Batman and Willy Wonka, to name a few of his subjects, said having a place for like-minded artists to share work based on popular culture gives the artists a sense of community seldom found in the fine art world.

“For the longest time [while] learning the arts, I always had that eye for pop and art,” Price said. “I wasn’t ashamed by it, but I didn’t feel welcomed in the fine art community because of it. Being able to work with these specialized galleries, meeting other artists and getting the chance to showcase with them is an honor and [it’s] great to know I’m not alone.”

Many of these artists said their love of television and film while growing up helped shape their present-day artwork.

Geoff Trapp, a New Jersey-based pop artist who creates original paintings, mixed-media works and prints for Gallery 1988, said he was fascinated as a kid by the film industry, which ultimately influenced his current references to films like “Raising Arizona” and “Goldeneye,” which appear in Trapp’s toys based on those films.

“A lot of people—when they’re younger—want to be involved in the film industry because there are all these great movies out there that influenced us so much when we were kids,” Trapp said. “That’s my influence. I find it a lot easier to draw from that well of fantasy and these great movies we grew up with.”

Some artists prefer to print their designs on novelty items such as stickers, lapel pins and other merchandise that appeal to a younger audience.

Twylamae, an illustrator from Melbourne, Australia, known for her “Seinfeld” designs, has garnered a dedicated following by sharing new work daily on her Instagram account, featuring original illustrations on her personal website and selling keychains to tote bags on her Etsy page, “Twylamaeshop.”

Twylamae said social media has allowed pop art to grow because artists can use their followers as a sort of focus group to see what their audiences like and respond positively to in real time.

“In this digital age, everyone loves to see things they recognize, things they relate to and things that make them laugh,” Twylamae said. “If you can combine those elements and turn them into works of art, people will respond well to them. We’re all sort of slaves to television and tabloids. It’s part of our daily lives. It just feels good to make light of that.”

London-based illustrator Nick “Thumbs” Thompson also found a cult following through Instagram. Thompson, who has only been creating his repurposed illustrations of mostly “Simpsons” and “Adventure Time” mashups for eight months, said the sudden interest in his doodles is mind-blowing and lucrative.

“It’s pretty crazy,” Thompson said. “When I started, I was just drawing Bart Simpson and making stickers, never thinking anyone would take it seriously. Now—eight months later—I have shops in California and Texas buying all my stuff to sell. There are people spending thousands of dollars on this stuff that I just mocked up on my computer. It’s crazy to think that it could be considered as proper artwork.”

This art movement may be on the rise, but it has had its setbacks—licensing disputes, accusations of copyright violation and the stigma attached to borrowing another artist’s work.

Trapp said even pop artists in the days of Claes Oldenburg and Robert Rauschenberg never got the amount of respect they deserved because of the repurposed images and icons in their pieces.

“We’re still viewed as the illustrators of the art world, even though a lot of stuff [pop artists] were doing was superior to what the fine art community was doing,” Trapp said. “I don’t know if we get a fair shake because of our affiliation with pre-existing media—we’re so closely tied to movies and the pop culture community.”

Martin Brochstein, senior vice president of Industry Relations and Information for the International Licensing Merchandisers’ Association said it is important for artists to realize the line between creating fan art and selling this type of artwork for a profit.

“The fact that 27 years down the road people still want to do this—that says something,” Brochstein said. “That’s the balance the creators and the owners try to strike—encouraging that interaction while doing what’s prudent in a financial and legal sense. Where the line gets crossed is when they want to profit from it. There’s a difference between making your own T-shirt for yourself with Bart in a situation of your own making, and going out and selling a thousand of those somewhere.”

One argument these artists use to circumvent copyright law is that they’re producing works of parody.

Jerry Glover, a partner at the law firm of Leavens, Strand and Glover—a Chicago firm specializing in entertainment and intellectual property law—said the law governing parody requires the work to make some sort of commentary on the original. The function of the commentary is to transform the original work into something new.

“There are exceptions to the rule,” Glover said. “The fair use defense says although things are protected by copyright, you have to be able to build on the work of others for progress in the arts and sciences. To be able to use a piece of someone’s copyrighted material in furtherance of another purpose is allowed, assuming you are not destroying the market for the original and you are only using as much as necessary for the purpose you have and that you are transforming the original into something new and different.”

Chicago illustrator and 2014 Columbia design alumnus Joe Flores—whose Instagram “joeflomontana” has nearly 9,000 followers—said he makes sure each of his designs has an original spin to avoid infringement.

Flores said artists have to carefully walk that fine line between appropriating someone else’s work and transformation.

“People are seeing how far they can get away with these designs before legal issues get involved,” Flores said. “There have been some pretty amazing pieces that have been shut down due to the fact it was bootlegged and not officially licensed. A lot of people understand the risk they are taking by doing this type of work, but they are just trying to put stuff out there that appeals to the audience.”

Jared “Circusbear” Flores, a designer toy artist who also shows work at Gallery 1988, and has no relation to Joe Flores, said the accessibility of digital images through the Internet conflicts with conventional notions of intellectual property ownership.

“It speaks to a much larger trend of a culture of repurposing,” Jared Flores said. “With the way social media has changed the way we repurpose images constantly, we consume imagery and redistribute it once we consume it. It speaks to loss of authorship, and as a culture, we have lost that sense of need over ownership of our work.”

Twylamae transforms some of her subjects, such as the “Seinfeld” characters and scenes from shows such as “Arrested Development,” into cartoon characters, which is a wholly new creation.

“Rather than replicating something to seem exactly like its original so we can sell it as a cheap knockoff, we are drawing inspiration to create an entirely new work of art that has a sense of familiarity combined with our own artistic integrity,” Twylamae said. “I’m not about cutting and pasting. I’m continually developing and refining my style so I’m creating products that will be recognizably ‘Twylamae.’”

“Simpsons” creator Groening appears to be supportive of the movement although one might expect someone in his position to fight back, according to Joe Flores.

In July 2015, an exhibit in Los Angeles featuring more than 70 international artists—including Joe Flores—highlighted original art dedicated to the spiky-haired hell-raiser Bart Simpson. Groening attended the exhibit to look at the worldwide artists keeping his character alive through their original works, Joe Flores said.

“It was on such a magnitude of anything you’ve ever seen before,” Joe Flores said. “It was just an entire gallery dedicated to Bart Simpson. It showed me that pop art is taking the world by storm and referencing these icons. Galleries are catching on to the trends of the masses to try to stay in tune with younger millennial crowds.”

Thompson said the artworks pay homage to the memories of popular characters and helps keep them alive. He said by creating and transforming these already well-known characters into something new, he is working to further the legacy of a beloved character.

“This type of art rejuvenates these characters and gives them a new lease on life,” Thompson said. “Whether it’s Bart Simpson or ‘Adventure Time,’ it’s always going to lead back to that original cartoon. It’s never going to do any harm to them.”

In times when social media, reality television and meme culture are taking over the airwaves, pop art helps communicate and act as a sort of satirical take on those ideas, Joe Flores said.

“Pop culture is this language we speak now. We communicate through something as small as using these characters and iconography,” Jared Flores said. “It is current and essential and it’s where we are now.”