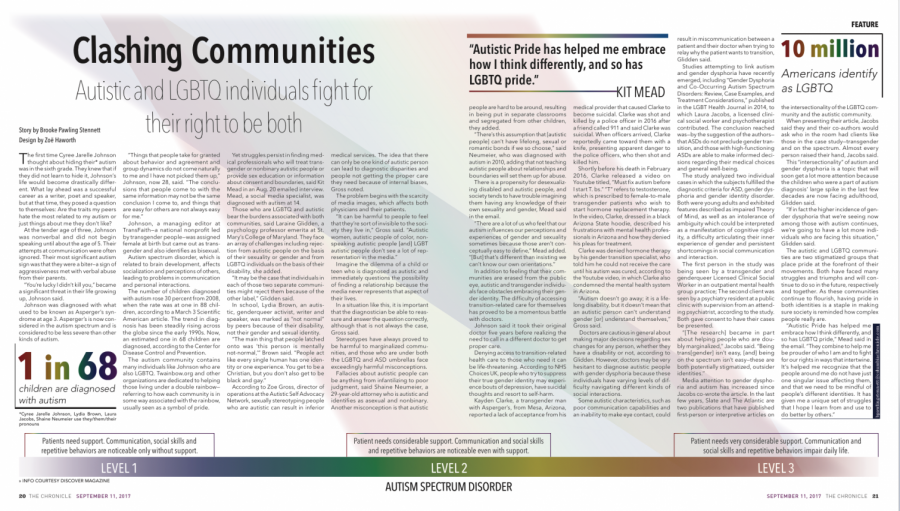

Clashing Communities: Autistic and LGBTQ individuals fight for their right to be both

Clashing Communities: Autistic and LGBTQ individuals fight for their right to be both

September 11, 2017

The first time Cyree Jarelle Johnson thought about hiding their* autism was in the sixth grade. They knew that if they did not learn to hide it, Johnson’s life would become drastically different. What lay ahead was a successful career as a writer, poet and speaker, but at that time, they posed a question to themselves: Are the traits my peers hate the most related to my autism or just things about me they don’t like?

At the tender age of three, Johnson was nonverbal and did not begin speaking until about the age of 5. Their attempts at communication were often ignored. Their most significant autism sign was that they were a biter—a sign of aggressiveness met with verbal abuse from their parents.

“You’re lucky I didn’t kill you,” became a significant threat in their life growing up, Johnson said.

Johnson was diagnosed with what used to be known as Asperger’s syndrome at age 3. Asperger’s is now considered in the autism spectrum and is considered to be less severe than other kinds of autism.

“Things that people take for granted about behavior and agreement and group dynamics do not come naturally to me and I have not picked them up,” Johnson, now 28, said. “The conclusions that people come to with the same information may not be the same conclusion I come to, and things that are easy for others are not always easy for me.”

Johnson, a managing editor at TransFaith—a national nonprofit led by transgender people—was assigned female at birth but came out as transgender and also identifies as bisexual.

Autism spectrum disorder, which is related to brain development, affects socialization and perceptions of others, leading to problems in communication and personal interactions.

The number of children diagnosed with autism rose 30 percent from 2008, when the rate was at one in 88 children, according to a March 3 Scientific American article. The trend in diagnosis has been steadily rising across the globe since the early 1990s. Now, an estimated one in 68 children are diagnosed, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

The autism community contains many individuals like Johnson who are also LGBTQ. Twainbow.org and other organizations are dedicated to helping those living under a double rainbow—referring to how each community is in some way associated with the rainbow, usually seen as a symbol of pride.

Yet struggles persist in finding medical professionals who will treat transgender or nonbinary autistic people or provide sex education or information about consent and boundaries, said Kit Mead in an Aug. 20 emailed interview. Mead, a social media specialist, was diagnosed with autism at 14.

Those who are LGBTQ and autistic bear the burdens associated with both communities, said Laraine Glidden, a psychology professor emerita at St. Mary’s College of Maryland. They face an array of challenges including rejection from autistic people on the basis of their sexuality or gender and from LGBTQ individuals on the basis of their disability, she added.

“It may be the case that individuals in each of those two separate communities might reject them because of the other label,” Glidden said.

In school, Lydia Brown, an autistic, genderqueer activist, writer and speaker, was marked as “not normal” by peers because of their disability, not their gender and sexual identity.

“The main thing that people latched onto was ‘this person is mentally not-normal,’” Brown said. “People act like every single human has one identity or one experience. You get to be a Christian, but you don’t also get to be black and gay.”

According to Zoe Gross, director of operations at the Autistic Self Advocacy Network, sexually stereotyping people who are autistic can result in inferior medical services. The idea that there can only be one kind of autistic person can lead to diagnostic disparities and people not getting the proper care they need because of internal biases, Gross noted.

The problem begins with the scarcity of media images, which affects both physicians and their patients.

“It can be harmful to people to feel that they’re sort of invisible to the society they live in,” Gross said. “Autistic women, autistic people of color, nonspeaking autistic people [and] LGBT autistic people don’t see a lot of representation in the media.”

Imagine the dilemma of a child or teen who is diagnosed as autistic and immediately questions the possibility of finding a relationship because the media never represents that aspect of their lives.

In a situation like this, it is important that the diagnostician be able to reassure and answer the question correctly, although that is not always the case, Gross said.

Stereotypes have always proved to be harmful to marginalized communities, and those who are under both the LGBTQ and ASD umbrellas face exceedingly harmful misconceptions.

Fallacies about autistic people can be anything from infantilizing to poor judgement, said Shaine Neumeier, a 29-year-old attorney who is autistic and identifies as asexual and nonbinary. Another misconception is that autistic people are hard to be around, resulting in being put in separate classrooms and segregated from other children, they added.

“There’s this assumption that [autistic people] can’t have lifelong, sexual or romantic bonds if we so choose,” said Neumeier, who was diagnosed with autism in 2010, adding that not teaching autistic people about relationships and boundaries will set them up for abuse.

There is a propensity for desexualizing disabled and autistic people, and society tends to have trouble imagining them having any knowledge of their own sexuality and gender, Mead said in the email.

“There are a lot of us who feel that our autism influences our perceptions and experiences of gender and sexuality sometimes because those aren’t conceptually easy to define,” Mead added. “[But] that’s different than insisting we can’t know our own orientations.”

In addition to feeling that their communities are erased from the public eye, autistic and transgender individuals face obstacles embracing their gender identity. The difficulty of accessing transition-related care for themselves has proved to be a momentous battle with doctors.

Johnson said it took their original doctor five years before realizing the need to call in a different doctor to get proper care.

Denying access to transition-related health care to those who need it can be life-threatening. According to NHS Choices UK, people who try to suppress their true gender identity may experience bouts of depression, have suicidal thoughts and resort to self-harm.

Kayden Clarke, a transgender man with Asperger’s, from Mesa, Arizona, reported a lack of acceptance from his medical provider that caused Clarke to become suicidal. Clarke was shot and killed by a police officer in 2016 after a friend called 911 and said Clarke was suicidal. When officers arrived, Clarke reportedly came toward them with a knife, presenting apparent danger to the police officers, who then shot and killed him.

Shortly before his death in February 2016, Clarke released a video on Youtube titled, “Must fix autism before I start T. bs.” “T” refers to testosterone, which is prescribed to female-to-male transgender patients who wish to start hormone replacement therapy. In the video, Clarke, dressed in a black Arizona State hoodie, described his frustrations with mental health professionals in Arizona and how they denied his pleas for treatment.

Clarke was denied hormone therapy by his gender transition specialist, who told him he could not receive the care until his autism was cured, according to the Youtube video, in which Clarke also condemned the mental health system in Arizona.

“Autism doesn’t go away; it is a lifelong disability, but it doesn’t mean that an autistic person can’t understand gender [or] understand themselves,” Gross said.

Doctors are cautious in general about making major decisions regarding sex changes for any person, whether they have a disability or not, according to Glidden. However, doctors may be very hesitant to diagnose autistic people with gender dysphoria because these indvidiuals have varying levels of difficulty navigating different kinds of social interactions.

Some autistic characteristics, such as poor communication capabilities and an inability to make eye contact, could result in miscommunication between a patient and their doctor when trying to relay why the patient wants to transition, Glidden said.

Studies attempting to link autism and gender dysphoria have recently emerged, including “Gender Dysphoria and Co-Occurring Autism Spectrum Disorders: Review, Case Examples, and Treatment Considerations,” published in the LGBT Health Journal in 2014, to which Laura Jacobs, a licensed clinical social worker and psychotherapist contributed. The conclusion reached was—by the suggestion of the authors—that ASDs do not preclude gender transition, and those with high-functioning ASDs are able to make informed decisions regarding their medical choices and general well-being.

The study analyzed two individual cases in which the subjects fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for ASD, gender dysphoria and gender identity disorder. Both were young adults and exhibited features described as impaired Theory of Mind, as well as an intolerance of ambiguity which could be interpreted as a manifestation of cognitive rigidity, a difficulty articulating their inner experience of gender and persistent shortcomings in social communication and interaction.

The first person in the study was being seen by a transgender and genderqueer Licensed Clinical Social Worker in an outpatient mental health group practice; The second client was seen by a psychiatry resident at a public clinic with supervision from an attending psychiatrist, according to the study. Both gave consent to have their cases be presented.

“[The research] became in part about helping people who are doubly marginalized,” Jacobs said. “Being trans[gender] isn’t easy, [and] being on the spectrum isn’t easy—these are both potentially stigmatized, outsider identities.”

Media attention to gender dysphoria and autism has increased since Jacobs co-wrote the article. In the last few years, Slate and The Atlantic are two publications that have published first-person or interpretive articles on the intersectionality of the LGBTQ community and the autistic community.

When presenting their article, Jacobs said they and their co-authors would ask who in the room had clients like those in the case study—transgender and on the spectrum. Almost every person raised their hand, Jacobs said.

This “intersectionality” of autism and gender dysphoria is a topic that will soon get a lot more attention because the children who were a part of autism diagnosis’ large spike in the last few decades are now facing adulthood, Glidden said.

“If in fact the higher incidence of gender dysphoria that we’re seeing now among those with autism continues, we’re going to have a lot more individuals who are facing this situation,” Glidden said.

The autistic and LGBTQ communities are two stigmatized groups that place pride at the forefront of their movements. Both have faced many struggles and triumphs and will continue to do so in the future, respectively and together. As these communities continue to flourish, having pride in both identities is a staple in making sure society is reminded how complex people really are.

“Autistic Pride has helped me embrace how I think differently, and so has LGBTQ pride,” Mead said in the email. “They combine to help me be prouder of who I am and to fight for our rights in ways that intertwine. It’s helped me recognize that the people around me do not have just one singular issue affecting them, and that we need to be mindful of people’s different identities. It has given me a unique set of struggles that I hope I learn from and use to do better by others.”