Downloading, subscription services changing music distribution

October 13, 2014

Since the commercial introduction of the compact disc in November 1982, music distribution has gone through multiple transformations and is now changing and becoming more popular than ever with online music downloading and interactive subscription services.

Robert DiFazio, adjunct faculty in Columbia’s Business & Entrepreneurship Department, said a la carte downloading, in which consumers download one particular song instead of buying an entire album, is one of the biggest changes the industry has experienced.

“It’s a lot more difficult to make your living off the sale of your recorded music products unless you are in the rarefied air of an artist who is widely recognizable,” DiFazio said. “Becoming a recognizable artist is what most people want, and profiting from the sale of your recorded music product on your way to becoming recognizable is almost impossible.”

Radiohead self-released its sixth studio album, In Rainbows, in 2007, using a “pay-as-you-wish” method, which meant that fans had the ability to choose how much they wanted to pay instead of dishing out the standard $15–20 one would usually pay for a CD.

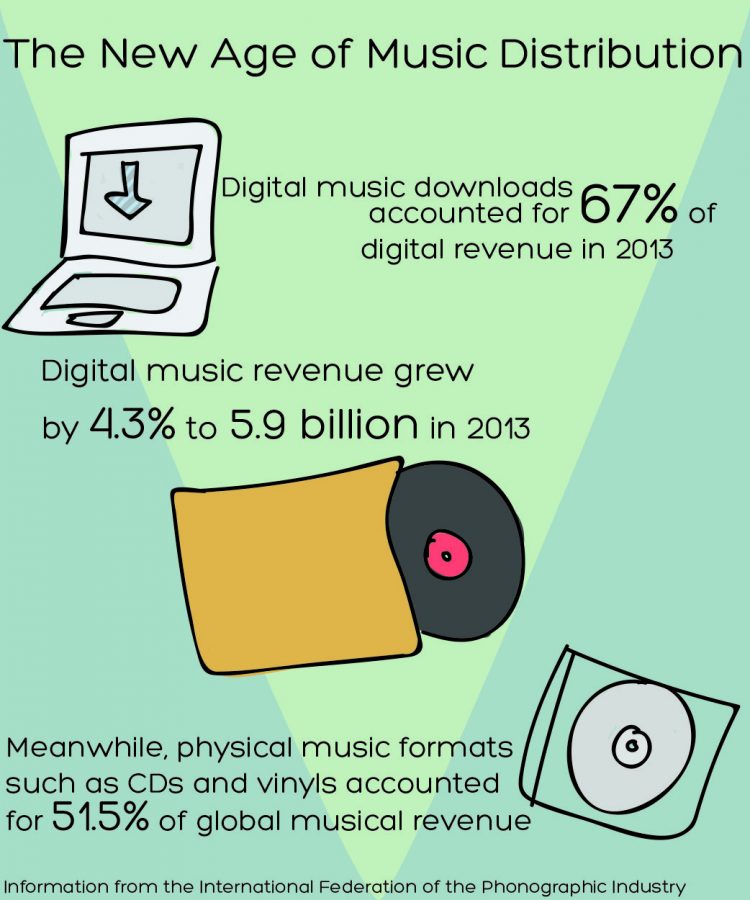

In a study conducted by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, the music industry’s digital revenue grew by 4.3 percent to $5.9 billion in 2013. The IFPI also reported that digital downloading remains a key revenue stream for the industry. Downloads account for 67 percent of digital revenue, said the study.

Despite the popularity of digital music, physical distribution still remains relevant to consumers. The IFPI reported that in 2013, physical music formats including CDs and vinyl accounted for 51.5 percent of all global music revenues.

Alex Heaney, a freshman music major, said although many people see physical forms of music as dying art forms, these physical forms might find their place in the future.

“[Physical forms of music] might even become stronger as things become more digitized,” Heaney said. “In other words, people [might] retaliate and start to want things on their own physically.”

August Bryan, the drummer for local band The Brass Kicks, said he prefers physical forms of music compared to digitally downloaded music. After The Brass Kicks released its first EP, Bryan said he bought 100 CDs and slowly burned their music onto the discs from his computer with the intent of using them to promote the band.

“By the time I told my bandmates I had 100 CDs on me, they said they already had our music downloaded to Soundcloud, Facebook and a couple other spots online,” Bryan said. “There wasn’t really much good to my CDs. We couldn’t really charge for them, which I thought we were going to do just to earn our money that we spent on CDs back.”

Subscription services such as Spotify, Pandora and Google Play are also changing the digital age of music because consumers are not directly buying recorded music products to own permanently, DiFazio said.

“Subscription streaming services didn’t seem to be catching on [in the mid-2000s],” DiFazio said. “But in the last several years, especially between 2012–2013, there was a seven to 10 percent increase in the sale of subscriptions for interactive streaming. That’s a system which basically means that the artist or whoever owns the sound recording is going to be paid based on how much they are played.”

With all the changes to music distribution, some have questioned whether digital downloads have degraded the value of music. The continuing issue of music piracy is that it undermines an artist’s efforts, Heaney said.

“There’s been kind of a war going on [between artists and piracy],” Heaney said. “In general, if you’re putting music online, there’s kind of an assumption that it could be illegally downloaded and could play into people’s ears no matter what you do to try and prevent it.”

DiFazio said musicians are receiving smaller percentages of digital download and interactive subscription service play profits because the money earned does not go directly into their pockets because the music is often owned by their record label.

“The basic premise is their music value is determined by the people who own it, which is not the artists,” DiFazio said. “The value of the recorded music products is not up to the artist. It’s up to negotiations between the record companies and music streaming services.”