OPINION: Blue Line construction disregards disabled people

April 15, 2019

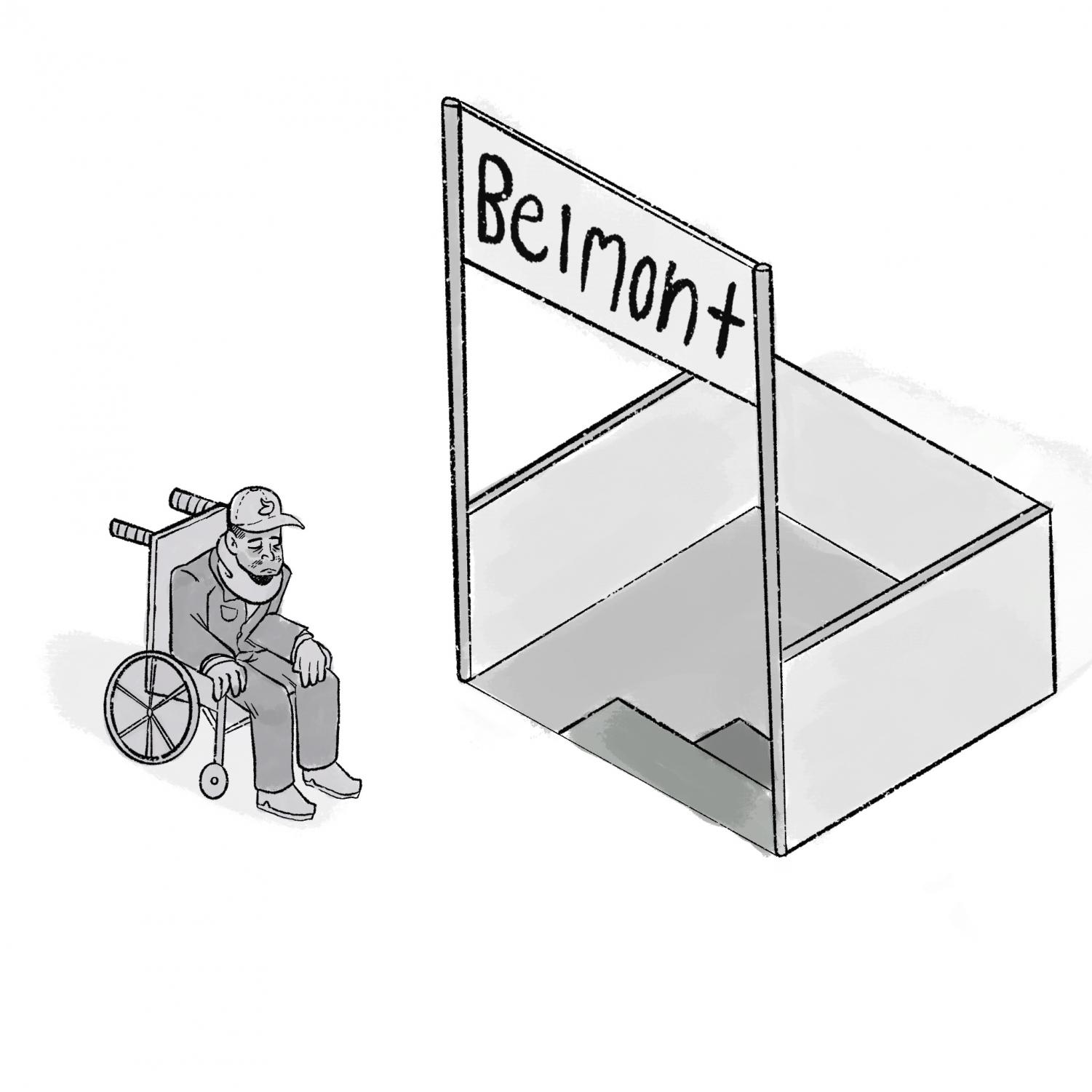

On the Northwest Side of the city, the Belmont Blue Line station recently benefited from $17 million in renovations. The additions included a flashy blue canopy, LED lighting, a new paint job, additional overhead heaters and a waiting area where bus passengers can pre-pay for their ride. What it did not include was an elevator to make the station accessible under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

According to a March 29 Block Club article, CTA President Dorval R. Carter Jr. estimated the cost of an elevator renovation at the Belmont stop at around $71 million. According to Carter, the CTA doesn’t currently have the money for such an expense yet, but it has pledged to make 100% of “L” stops accessible over the next 20 years, a promise that will cost $2.1 billion.

It is insulting to people who need elevators to put millions of dollars toward other largely superficial changes. While the Belmont station is between two other accessible Blue Line stops—Addison and Logan Square—neither of those can be accessed via a CTA bus from the Belmont stop, making it difficult for disabled people who live or work in that area to reach either of them.

Currently, all CTA buses and trains are accessible to board, but only 70% of “L” stations have elevators, and many bus stops are on uneven sidewalks, making it difficult for those with mobility issues to navigate them, according to a Nov. 15, 2018, Metro Magazine article. There are also issues with buses’ recorded stop announcements or the electronic board that displays the name of each stop, making them inaccessible to blind and deaf people without additional assistance.

Pace buses, the paratransit option currently presented to disabled people, are unreliable and often receive complaints from riders, according to an October 2017 report by advocacy group Access Living. Pace buses coordinate pick-ups and drop-offs scheduled 24 hours in advance, but only 62% of 186 reported paratransit pick-ups were on time that year. Forty-one percent of these late pick-ups were late by more than 40 minutes, and 16% were late by more than an hour.

Even transit systems that are accessible for people with disabilities are often subpar— an extension of neglectful treatment in major cities, such as Chicago. Factors that non-disabled people do not have to think about—such as a long walk to a bus stop, navigating a poorly-maintained sidewalk or hiking up the stairs to catch a train—are things that can make it impossible for many disabled people to get around the city. Should disabled folks try to use the system supported by their tax dollars, they might risk arriving an hour late.

This host of problems is unacceptable. For decades, people with disabilities have been treated as an afterthought to be accommodated when time or money becomes available, instead of as a priority for which time and money should be made available.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s website, 7.1% of Chicago’s population under the age of 65 from 2013–2017 was disabled. That is about 193,000 people. For a public transit system to fail that many residents is intolerable, and to spend money on largely unnecessary changes instead of putting funds toward ADA compliance is even worse. Hundreds of thousands of people are being treated as if they are less deserving of dependable, accessible transportation, and that needs to change.