The future of labels: A glimpse into the use of sexual identities today

The future of labels: A glimpse into the use of sexual identities today

February 13, 2017

Megan Harvey was in college in the U.K. when she texted her father with the words, “I have something really important I need to say.”

She was about to come out as bisexual. Her dad gave a vague reply, but Harvey was nervous—so much so that she calculated the distance between her and the family friend she could move in with if things went awry.

Thankfully it all turned out okay, Harvey said.

“For me and most bisexual people, you feel like you need to confirm your identity or you think that sometimes you’re wrongfully labeling yourself,” Harvey said.

Harvey is not the only millennial who has struggled with sexual identity. Labeling yourself can be a monumental moment. However, some people do not feel that they fit any kind of label and prefer to not identify with any sexuality or gender identity.

YouGov, an international internet-based market research firm in the U.K., conducted a survey about how British adults placed themselves on the sexuality spectrum, “zero” being heterosexual and “six” being homosexual.

Of the 18–24 demographic, 43 percent ranked themselves between one and five, while 81 percent of 40–59 year olds identified as either completely heterosexual or homosexual. Within the younger generation, the results show that labels for sexual orientation and gender identity have become increasingly complex.

However, that same complexity has sparked a widespread debate about whether society should get rid of labels for sexual orientation and identity even though they have been around for decades.

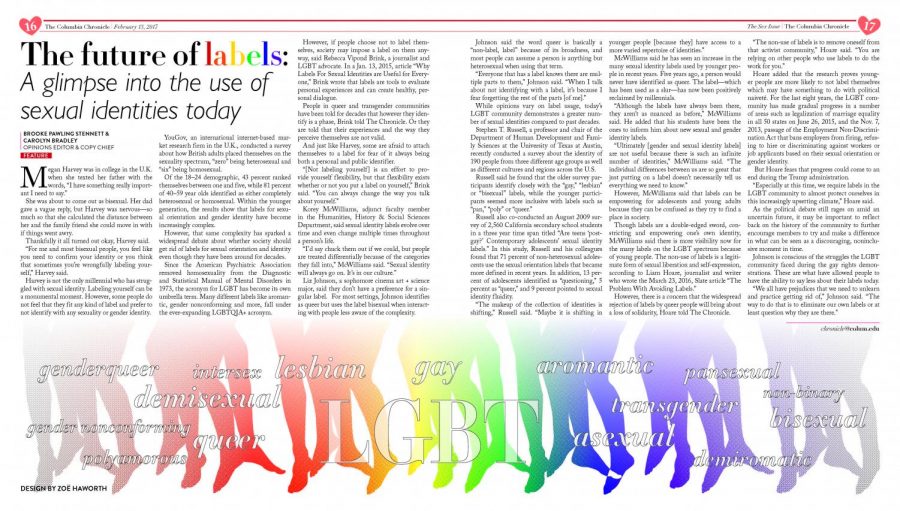

Since the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1973, the acronym for LGBT has become its own umbrella term. Many different labels like aromantic, gender nonconforming and more, fall under the ever-expanding LGBTQIA+ acronym.

However, if people choose not to label themselves, society may impose a label on them anyway, said Rebecca Vipond Brink, a journalist and LGBT advocate. In a Jan. 13, 2015, article “Why Labels For Sexual Identities are Useful for Everyone,” Brink wrote that labels are tools to evaluate personal experiences and can create healthy, personal dialogue.

People in queer and transgender communities have been told for decades that however they identify is a phase, Brink told The Chronicle. Or they are told that their experiences and the way they perceive themselves are not valid.

And just like Harvey, some are afraid to attach themselves to a label for fear of it always being both a personal and public identifier.

“[Not labeling yourself] is an effort to provide yourself flexibility, but that flexibility exists whether or not you put a label on yourself,” Brink said. “You can always change the way you talk about yourself.”

Korey McWilliams, adjunct faculty member in the Humanities, History & Social Sciences Department, said sexual identity labels evolve over time and even change multiple times throughout a person’s life.

“I’d say chuck them out if we could, but people are treated differentially because of the categories they fall into,” McWilliams said. “Sexual identity will always go on. It’s in our culture.”

Liz Johnson, a sophomore cinema art + science major, said they don’t have a preference for a singular label. For most settings, Johnson identifies as queer but uses the label bisexual when interacting with people less aware of the complexity.

Johnson said the word queer is basically a “non-label, label” because of its broadness, and most people can assume a person is anything but heterosexual when using that term.

“Everyone that has a label knows there are multiple parts to them,” Johnson said. “When I talk about not identifying with a label, it’s because I fear forgetting the rest of the parts [of me].”

While opinions vary on label usage, today’s LGBT community demonstrates a greater number of sexual identities compared to past decades.

Stephen T. Russell, a professor and chair of the Department of Human Development and Family Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin, recently conducted a survey about the identity of 190 people from three different age groups as well as different cultures and regions across the U.S.

Russell said he found that the older survey participants identify closely with the “gay,” “lesbian” or “bisexual” labels, while the younger participants seemed more inclusive with labels such as “pan,” “poly” or “queer.”

Russell also co-conducted an August 2009 survey of 2,560 California secondary school students in a three year time span titled “Are teens ‘post-gay?’ Contemporary adolescents’ sexual identity labels.” In this study, Russell and his colleagues found that 71 percent of non-heterosexual adolescents use the sexual orientation labels that became more defined in recent years. In addition, 13 percent of adolescents identified as “questioning,” 5 percent as “queer,” and 9 percent pointed to sexual identity fluidity.

“The makeup of the collection of identities is shifting,” Russell said. “Maybe it is shifting in younger people [because they] have access to a more varied repertoire of identities.”

McWilliams said he has seen an increase in the many sexual identity labels used by younger people in recent years. Five years ago, a person would never have identified as queer. The label—which has been used as a slur—has now been positively reclaimed by millennials.

“Although the labels have always been there, they aren’t as nuanced as before,” McWilliams said. He added that his students have been the ones to inform him about new sexual and gender identity labels.

“Ultimately [gender and sexual identity labels] are not useful because there is such an infinite number of identities,” McWilliams said. “The individual differences between us are so great that just putting on a label doesn’t necessarily tell us everything we need to know.”

However, McWilliams said that labels can be empowering for adolescents and young adults because they can be confused as they try to find a place in society.

Though labels are a double-edged sword, constricting and empowering one’s own identity, McWilliams said there is more visibility now for the many labels on the LGBT spectrum because of young people. The non-use of labels is a legitimate form of sexual liberation and self-expression, according to Liam Hoare, journalist and writer who wrote the March 23, 2016, Slate article “The Problem With Avoiding Labels.”

However, there is a concern that the widespread rejection of labels by queer people will bring about a loss of solidarity, Hoare told The Chronicle.

“The non-use of labels is to remove oneself from that activist community,” Hoare said. “You are relying on other people who use labels to do the work for you.”

Hoare added that the research proves younger people are more likely to not label themselves which may have something to do with political naiveté. For the last eight years, the LGBT community has made gradual progress in a number of areas such as legalization of marriage equality in all 50 states on June 26, 2015, and the Nov. 7, 2013, passage of the Employment Non-Discrimination Act that bans employers from firing, refusing to hire or discriminating against workers or job applicants based on their sexual orientation or gender identity.

But Hoare fears that progress could come to an end during the Trump administration.

“Especially at this time, we require labels in the LGBT community to almost protect ourselves in this increasingly upsetting climate,” Hoare said.

As the political debate still rages on amid an uncertain future, it may be important to reflect back on the history of the community to further encourage members to try and make a difference in what can be seen as a discouraging, noninclusive moment in time.

Johnson is conscious of the struggles the LGBT community faced during the gay rights demonstrations. These are what have allowed people to have the ability to say less about their labels today.

“We all have prejudices that we need to unlearn and practice getting rid of,” Johnson said. “The way to do that is to eliminate our own labels or at least question why they are there.”