Non-dominant hand influences thumb’s evolution

Non-dominant hand influences thumb’s evolution

September 29, 2014

Throughout early human history, the development of tools such as hand-axes, flints and flakes is believed to have influenced the evolution of culture and anatomy.

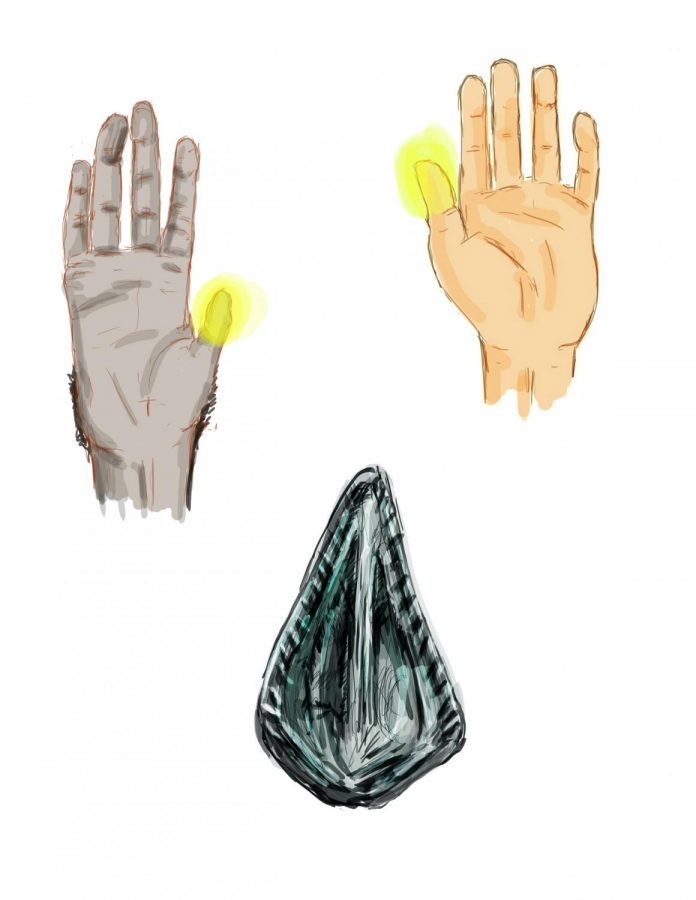

In a Sept. 6 study published in the Journal of Human Evolution, researchers from the University of Kent’s School of Anthropology and Conservation in the U.K. analyzed the manipulative pressures and frequency of use the thumb and fingers of the non-dominant hand undergo during flintknapping—the process of chipping away material from stone cores to produce tools such as hand-axes wielded by early ancestors of humans.

“Manipulative force is derived from the amount of pressure you’re exerting while making these tools,” said Alastair Key, lead researcher for the study and a Ph. D. candidate in the University of Kent’s Biological Anthropology Department.

Key said the main differences seen between human and primate hands are the musculature, size and strength output ratios between the thumbs and fingers. These changes indicate that manipulative pressures led to the selection of a larger and more robust thumb in humans. Key pointed to the example of Kanzi, a Bonobo chimpanzee who has famously been taught to flintknap.

“One of [Kanzi’s] problems was that he could not hold the stone core particularly well,” Key said. “He wasn’t able to secure it [with his non-dominant hand] because his thumb couldn’t get into position over the top of it. This is obviously something modern humans can do.”

According to Erin Marie Williams-Hatala, a Ph. D. and assistant professor of biology at Chatham University in Pittsburgh, small changes in the anatomy of the primate hand resulted in big functional differences for modern humans. These adaptations to selective pressures—like stone tool production—have resulted in greater grip strength and the ability to rotate both the thumb and pinky to form a unique cupping gesture.

“The changes that are taking place in the human hand and wrist are small,” Williams-Hatala said. “But because we have this really long, really robust thumb that is quite mobile, we can forcefully oppose it with our other digits.”

Williams-Hatala said for a behavior to elicit a selective response, it has to meet a minimum of two criteria: It has to be adaptively significant—important to the survival of the organism—and it has to induce some kind of new biological demand. In this instance, stone tools fit the bill.

“The important thing to keep in mind whenever we’re talking about stone tools and hand evolution is it’s sort of like looking for your keys under a streetlight,” said Carol Ward, a Ph. D. and director of anatomical sciences and curative professor of anatomy at the University of Missouri. “They could be anywhere, but you can only see under the streetlight, so that’s where you look.”

In a paper published Jan. 7 in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science, Ward and her team presented evidence for the earliest fully modern human hand in the fossil record, which was dated to 1.42 million years ago.

“Right around 1.6 million years ago, we see a much more advanced kind of hand-axe appear,” Ward said. “That’s right around when we see this change in the hand, so it may indicate a step up in how important the tools were, that they were using them all of the time.”

Ward said stone tools are what appear early on in the archaeological record. This does not mean that hominid forerunners were not also using implements like branches, bones or sticks as tools to interact with their environment, but that those objects do not preserve over long periods of time as well as stone.

“We need to keep in mind that because of how fossil preservation works, there will be pieces of the puzzle we’ll never see in the record,” Ward said. “We might only see the stones, but it doesn’t mean that that’s the most important behavior we were doing with our hands.”

Key said the study showed a lot of variation of force pressure depending on how the hands were manipulating the stone, ranging from a couple of hundred grams to several kilograms of pressure.

“There doesn’t have to be a massive recruitment [of force] for there to be a selective pressure in place,” Key said. “If you look at something that requires very delicate motions, like the repetitive strain of playing the piano, there’s still that pressure and strain on the hands.”

According to Key, while some of the values reported in his research appear to be low, they do not necessarily represent the forces being exerted through the fingers and thumb when they are being recruited for use but reference the “zero” value—the measurement of force when the thumb is recruited without other fingers. He said even a low amount of pressure exerted on the hands of humanity’s primate ancestors from a habitual action, like making and using stone tools, could still result in a very pronounced effect on how they evolve.

Williams-Hatala said primates perform a variety of behaviors with their hands and wrists that humans cannot, like knuckle walking and leaping between trees. Although some of the evolutionary changes that resulted in human hands developing as they have also allow for improved dexterity, a different variety of grips and degrees of strength position.

“But if you have to have a thumb war with a chimpanzee, as long as he doesn’t rip your thumb off, you’re going to win,” she said.