Artistry of game design: Video games blend film, theater, architecture to create new worlds

September 3, 2021

Editor’s note: This article is one in a series of stories from the Communication Department’s award-winning Echo magazine, featured this summer on the Chronicle site.

_____________________________________

William Chyr expected to finish his first video game design project and then move on to another art form. He didn’t know he’d be channeling his architectural influences in the process.

“I was doing glasswork and metalwork, and this was just another medium that I was going to explore,” says Chyr, who is a Chicago-based artist. “[I thought,] I’ll spend three months on this and then maybe move on to paper sculptures to see if that works. It ended up taking me seven years to finish.”

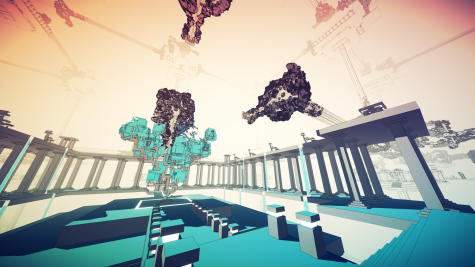

With a game design that draws from brutalist-inspired architecture, “Manifold Garden” lures players into an Escher-inspired playground, where structures are both limitless and confined at the same time.

Video games have become an art form for artists and designers to blend facets of different media and change the way audiences experience their work.

Jonathan Kinkley, owner of Chicago Gamespace, a gallery space dedicated to the design and social impact of video games, says many games are the sum of other artistic media, such as animation, music and cinematography, tied together through an interactive experience.

“I find video games endlessly fascinating and have since I was a kid,” Kinkley says. “I really think the potential of the medium is just starting to be tapped in a larger way, and it’s different than other media that have come before it.”

For example, narrative-focused titles such as “Kentucky Route Zero,” a point-and-click adventure game with surrealist and Americana-like themes, were developed with episodic acts in mind.

The game’s creators, Jake Elliot and Tamas Kemenczy of Cardboard Computer, looked at theater scripts for reference to create the fictional places and characters surrounding Route Zero.

In 2009, Chyr learned how to make elaborate balloon installations through a University of Chicago student organization, Le Vorris and Vox Circus.

After graduating the same year, he moved from one artist residency to another. The work became frustrating, Chyr says, as his sculptures and installations became more elaborate and less contemporary. He felt typecasted by the work, and eventually he was getting calls to make company logos rather than art.

Chyr says “Manifold Garden” was inspired by the 2012 film “Inception” and was initially modeled on Valve Software’s acclaimed puzzle-platformer, “Portal.” Even the original version of the game was named “Relativity” after M.C. Escher’s famous lithograph print.

Early on, “Manifold Garden” was solely built on the gravity-shifting game mechanic and consisted mostly of puzzles leading into one another, until early play-testing showed people were getting fatigued by the repetition and pacing of the puzzles.

“Game design is at its best when it is giving you an experience that you haven’t had before,” says Jacob Mooney, game designer at Level Ex, a developer that creates video games for doctors. “We’re in charge of bringing out emotions too, but we’re in charge of bringing out specific experiences.”

Mooney, who also designs board games on his own time, says creating experiences in video games relies on how the game interacts with the player. He points to “Hades,” a roguelike action role-playing video game by Supergiant Games, that uses different storylines and events that are triggered after the character dies, to encourage the player to progress further.

Other genres, including strategy simulation games, focus on putting the player in a specific job or profession, Mooney says. For example, Dinosaur Polo Club‘s “Mini Metro” puts the player in the shoes of a city planner, managing destinations and routes for the Chicago Transit Authority.

To remedy user fatigue, Chyr used influences of architects Frank Lloyd Wright and Tadao Ando to add accents and texture to “Manifold Garden’s” environment, and ultimately give the player a break in between each puzzle.

“The game itself is just really brilliant and a breakthrough. It’s greater than the sum of its parts,” Kinkley says. “It will never get old to me that the universe is wrapped around itself.”

Combined with the infinite generation of the environment, players can see how the ornamental details of Wright’s and Ando’s sense of scale guide them both away and toward new areas.

“Manifold Garden” has been out on every platform since August 2020, and though Chyr says he did not expect the design process to last as long as it did, he plans on continuing in game design and focusing more on operating the studio as a team.

“It’d be awesome to see my work at the Art Institute [of Chicago] one day, but that’s less interesting to me now,” Chyr says. “I shipped ‘Manifold Garden’ and the feeling I’m left with is just that there’s way more in this medium and the industry that I don’t know about, and that’s exciting.”