MENTAL HEALTH ISSUE

U.S. colleges and universities rely on adjuncts to do the majority of teaching, but under a model that makes them essentially gig workers, most part-time instructors don’t know from one semester to the next if they will have a class to teach.

That anxiety has increased as higher education faces declining enrollment and pressure from their board of trustees to reduce costs and for some, like Columbia, to reduce budget deficits.

A study done by psychologists Gretchen M. Reevy and Grace Deason found that non-tenure employees whose positions are determined per term are at risk of experiencing anxiety and depression. They make up 70% of faculty members in higher education.

At Columbia, part-time instructors are also the majority of faculty, numbering 584 in Fall 2023, which was more than double the 221 full-time faculty that semester. During the current Spring 2024 semester there are now 436 part-time faculty and 243 full-time faculty.

“It’s just really hard to be an adjunct because you live term-to-term and you never know what classes you’re going to be scheduled for,” said Cari Beecham-Bautista, an instructor in the Humanities, History and Social Sciences Department, who has been teaching at the college since 2000.

While Beecham-Bautista typically teaches three courses per semester, this spring she is only teaching two. One of the main reasons she originally loved teaching at Columbia was because she could count on a consistent schedule each semester, which was rare for adjunct positions at other institutions.

“Adjuncts, compared to full-timers, have to have material for so many different courses ready because I never know what class I’m gonna get,” she said. “Columbia has been nice because, generally, I know what class I’m teaching.”

Some instructors choose to teach part-time because the schedule can be flexible. Some adjuncts work a full-time industry job, which provides their primary income. However, for a lot of part-time instructors, this flexibility isn’t a choice and can be difficult to manage.

At Columbia, the historic seven-week strike last fall added to the stress. The ongoing financial challenges have made it worse.

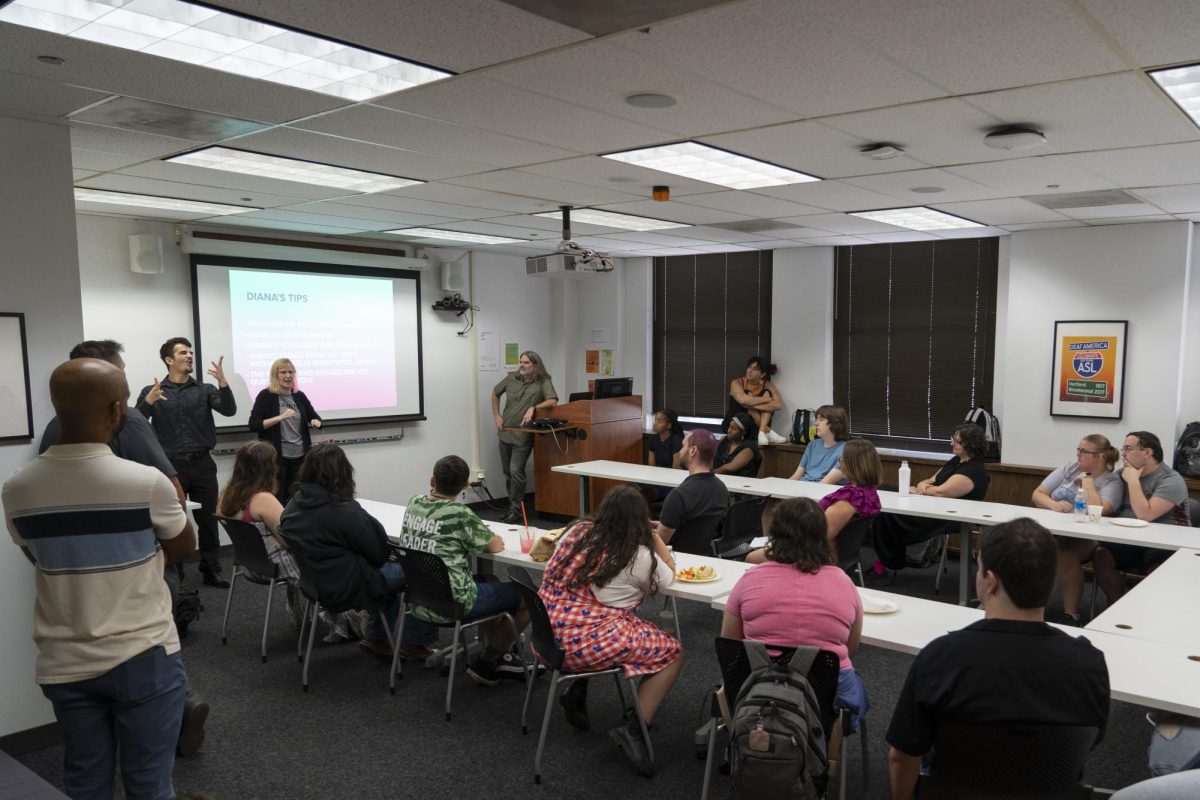

Diana Vallera, president of the Columbia Faculty Union and a part-time instructor in the Photography Department, initially agreed to talk for this story but then deferred, telling a reporter that Delia Pless, the union’s publications chair and a part-time instructor in the English and Creative Writing Department, would reach out. Pless did not.

The strike ended with a new contract for part-time instructors, who got a pay increase, course guarantees based on student enrollment, compensation for larger class sizes, new healthcare benefits and a seat at the table for decisions made around course offerings and reductions.

But that has been tempered by fewer course offers this spring and plans to merge or close programs to address the $38 million deficit, which nearly doubled during the strike. Some of the more junior part-time instructors did not get classes for Spring 2024 and will not get course offers in the fall because there are not enough sections to teach and because the contract gives available offerings first to the most senior part-time instructors. That means some adjuncts at the college are unsure if they will ever teach at Columbia again.

Richard Laurent, an adjunct instructor who teaches cartooning at Columbia, said he doesn’t know yet if he will be teaching a course this coming fall semester. Laurent typically teaches two courses per semester, but three days before the start of the spring 2024 semester, one of his classes was cut.

I decided my loyalty would lie with Columbia College,” Laurent said. “But the challenges have to do with our renewing our contracts and the breakdown in negotiations we’ve had with the administration.”

It’s not just at Columbia where working conditions for adjunct instructors remain frustrating, but an issue that’s nationwide.

“The biggest challenge of being an adjunct or a part-time instructor is the lack of stability or lack of predictability,” said Andrea Herrera, an adjunct professor at the University of Oregon and online instructor at Missouri State University.

Herrera said they will not be teaching at the University of Oregon next semester because their current contract only allows them to teach for three years. Although their department supported them in their petition to be reclassified as a tenured full-time professor, they were denied.

“Many qualified people do not end up getting jobs as full-time professors because there literally aren’t enough of them,” Herrera said. “So it’s like a numbers problem.”

Throughout Herrera’s time as an adjunct, they said they’ve experienced other problems, like feelings of alienation from full-time faculty. In one instance, they weren’t notified about a dangerous person on campus, an alert that wasn’t sent out to part-time faculty.

Herrera also said their pay remains low at $5,000 per course per semester and healthcare is only an option through the school if they pay for it themselves.

Many adjunct instructors rely on other jobs to sustain enough income. “I do all kinds of things on the side. My primary line of work at this point is I am a gallery painter,” Laurent said. “I’m an oil painter basically. But for a number of years, I was a magazine illustrator.”

He said his teaching position is currently his primary source of income.

“The way I’ve always coped with it is that I have worked in a lot of different places so that hopefully if availability is low in one place, I’ll get more availability in another place,” Beecham-Bautista said.

In addition to teaching at Columbia, she also teaches two to three online courses at the College of Dupage each semester.

Many adjuncts said they rely on their unions to get them through the changes and uncertainty. “The most important thing through the union for me is the solidarity; they have literally saved my job twice,” Laurent said.

Beecham-Bautista said adjuncts have always faced the uncertainty of whether they will get courses “but this just feels way worse, because it feels like long-term.”

For those who want to continue teaching, there aren’t many other options to phase out of being part-time. Beecham-Bautista said once you become an adjunct, it can be difficult to transition into a different job.

“To get a full-time job, you usually have to be willing to move and I wasn’t willing to move,” she said. Which for her and her family isn’t an option.

“Those full-time teaching positions are just not available. So if you want to teach, this is kind of a lot of people’s only option.”

Laurent said during the college’s part-time faculty strike, he was outside picketing every day. Since he is a cartoonist he made some into signs during the strike. “Humor did help me a great deal,” he said.

While a lot of unions are working towards creating more job security and predictability, many adjunct instructors are using short-term tools to deal with the stress that comes along with the job.

“I do yoga almost every day, I talk to people who understand,” Herrera said. They also said they have a food pantry out of their home that they work on as a way to relieve stress. “I go to therapy. I’m on Prozac,” they added.

Many adjunct instructors say they need conditions to change in order to feel a sense of security at work.

“I think in general, if there was just some sort of stability, for adjuncts, just even knowing at the beginning of the year, how many classes you would be assigned, that would make a huge difference in our lives,” Beecham-Bautista said. “I’m kind of able to put up with the indignities of adjunct life because I just love what happens in the classroom, specifically at Columbia.”

Copy Edited by Myranda Diaz