Young adult fiction gets its own coming-of-age story

Young adult fiction gets its own coming-of-age story

September 26, 2016

Sandie Angulo Chen is not the reader who comes to mind when literary critics dismiss young adult fiction as childish or second rate. A graduate of Columbia University, 40-year-old Chen has been a professional writer and film critic since 1998 at publications like Entertainment Weekly and Common Sense Media.

When Chen is not writing or taking care of her three children, she and her sister run a website called TeenLitRocks.com, a site that celebrates YA through reviews.

As an advocate for YA, Chen argues it can hold its own against even the most compelling and complex fiction published today.

“I consider myself incredibly well read,” Chen said. “There are YA books that have more complicated plots and deep substance themes than in mass paperback fiction or what some call women’s fiction.”

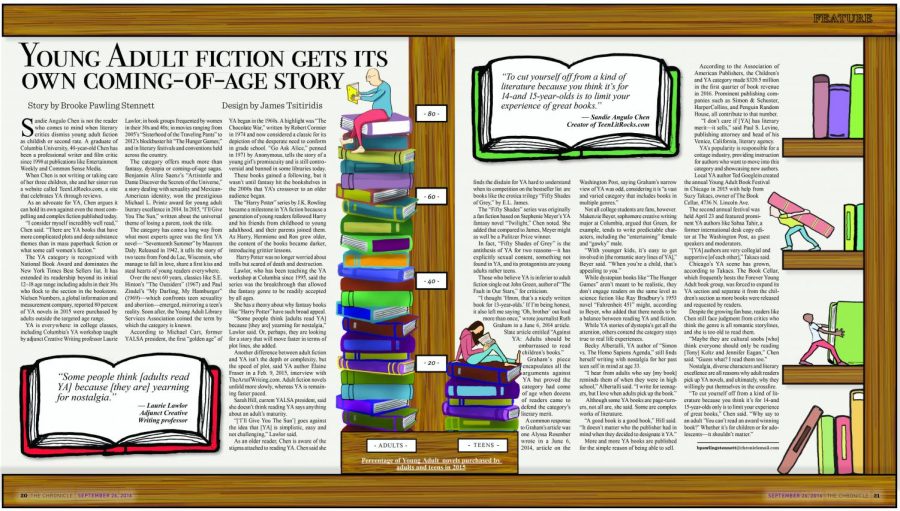

The YA category is recognized with National Book Award and dominates the New York Times Best Sellers list. It has extended its readership beyond its initial 12–18 age range including adults in their 30s who flock to the section in the bookstore. Nielsen Numbers, a global information and measurement company, reported 80 percent of YA novels in 2015 were purchased by adults outside the targeted age range.

YA is everywhere: in college classes, including Columbia’s YA workshop taught by adjunct Creative Writing professor Laurie Lawlor; in book groups frequented by women in their 30s and 40s; in movies ranging from 2005’s “Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants” to 2012’s blockbuster hit “The Hunger Games;” and in literary festivals and conventions held across the country.

The category offers much more than fantasy, dystopia or coming-of-age sagas. Benjamin Alire Saenz’s “Artistotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe,” a story dealing with sexuality and Mexican-American identity, won the prestigious Michael L. Printz award for young adult literary excellence in 2014. In 2015, “I’ll Give You The Sun,” written about the universal theme of losing a parent, took the title.

The category has come a long way from what most experts agree was the first YA novel— “Seventeenth Summer” by Maureen Daly. Released in 1942, it tells the story of two teens from Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, who manage to fall in love, share a first kiss and steal hearts of young readers everywhere.

Over the next 60 years, classics like S.E. Hinton’s “The Outsiders” (1967) and Paul Zindel’s “My Darling, My Hamburger” (1969)—which confronts teen sexuality and abortion—emerged, mirroring a teen’s reality. Soon after, the Young Adult Library Services Association coined the term by which the category is known.

According to Michael Cart, former YALSA president, the first “golden age” of YA began in the 1960s. A highlight was “The Chocolate War,” written by Robert Cormier in 1974 and now considered a classic for its depiction of the desperate need to conform in grade school. “Go Ask Alice,” penned in 1971 by Anonymous, tells the story of a young girl’s promiscuity and is still controversial and banned in some libraries today.

These books gained a following, but it wasn’t until fantasy hit the bookshelves in the 2000s that YA’s crossover to an older audience began.

The “Harry Potter” series by J.K. Rowling became a milestone in YA fiction because a generation of young readers followed Harry and his friends from childhood to young adulthood, and their parents joined them. As Harry, Hermione and Ron grew older, the content of the books became darker, introducing grittier lessons.

Harry Potter was no longer worried about trolls but scared of death and destruction.

Lawlor, who has been teaching the YA workshop at Columbia since 1995, said the series was the breakthrough that allowed the fantasy genre to be readily accepted by all ages.

She has a theory about why fantasy books like “Harry Potter” have such broad appeal.

“Some people think [adults read YA] because [they are] yearning for nostalgia,” Lawlor said. Or, perhaps, they are looking for a story that will move faster in terms of plot lines, she added.

Another difference between adult fiction and YA isn’t the depth or complexity, but the speed of plot, said YA author Elaine Fraser in a Feb. 9, 2015, interview with TheArtofWriting.com. Adult fiction novels unfold more slowly, whereas YA is remaining faster paced.

Sarah Hill, current YALSA president, said she doesn’t think reading YA says anything about an adult’s maturity.

“[‘I’ll Give You The Sun’] goes against the idea that [YA] is simplistic, easy and not challenging,” Lawlor said.

As an older reader, Chen is aware of the stigma attached to reading YA. Chen said she finds the disdain for YA hard to understand when its competition on the bestseller list are books like the erotica trilogy “Fifty Shades of Grey,” by E.L. James.

The “Fifty Shades” series was originally a fan fiction based on Stephenie Meyer’s YA fantasy novel “Twilight,” Chen noted. She added that compared to James, Meyer might as well be a Pulitzer Prize winner.

In fact, “Fifty Shades of Grey” is the antithesis of YA for two reasons—it has explicitly sexual content, something not found in YA, and its protagonists are young adults rather teens.

Those who believe YA is inferior to adult fiction single out John Green, author of “The Fault in Our Stars,” for criticism.

“I thought ‘Hmm, that’s a nicely written book for 13-year-olds.’ If I’m being honest, it also left me saying ‘Oh, brother’ out loud more than once,” wrote journalist Ruth Graham in a June 6, 2014 article. Slate article entitled “Against YA: Adults should be embarrassed to read children’s books.”

Graham’s piece encapsulates all the arguments against YA but proved the category had come of age when dozens of readers came to defend the category’s literary merit.

A common response to Graham’s article was one Alyssa Rosenber wrote in a June 6, 2014, article on the Washington Post, saying Graham’s narrow view of YA was odd, considering it is “a vast and varied category that includes books in multiple genres.”

Not all college students are fans, however. Makenzie Beyer, sophomore creative writing major at Columbia, argued that Green, for example, tends to write predictable characters, including the “entertaining” female and “gawky” male.

“With younger kids, it’s easy to get involved in [the romantic story lines of YA],” Beyer said. “When you’re a child, that’s appealing to you.”

While dystopian books like “The Hunger Games” aren’t meant to be realistic, they don’t engage readers on the same level as science fiction like Ray Bradbury’s 1953 novel “Fahrenheit 451” might, according to Beyer, who added that there needs to be a balance between reading YA and fiction.

While YA stories of dystopia’s get all the attention, others contend the category stays true to real life experiences.

Becky Albertalli, YA author of “Simon vs. The Homo Sapiens Agenda,” still finds herself writing with nostalgia for her past teen self in mind at age 33.

“I hear from adults who say [my book] reminds them of when they were in high school,” Albertalli said. “I write for teenagers, but I love when adults pick up the book.”

Although some YA books are page-turners, not all are, she said. Some are complex works of literature.

“A good book is a good book,” Hill said. “It doesn’t matter who the publisher had in mind when they decided to designate it YA.”

More and more YA books are published for the simple reason of being able to sell.

According to the Association of American Publishers, the Children’s and YA category made $320.5 million in the first quarter of book revenue in 2016. Prominent publishing companies such as Simon & Schuster, HarperCollins, and Penguin Random House, all contribute to that number.

“I don’t care if [YA] has literary merit—it sells,” said Paul S. Levine, publishing attorney and head of his Venice, California, literary agency.

YA’s popularity is responsible for a cottage industry, providing instruction for authors who want to move into this category and showcasing new authors. Local YA author Ted Goeglein created the annual Young Adult Book Festival in Chicago in 2015 with help from Suzy Takacs, owner of The Book Cellar, 4736 N. Lincoln Ave.

The second annual festival was held April 23 and featured prominent YA authors like Sabaa Tahir, a former international desk copy editor at The Washington Post, as guest speakers and moderators.

“[YA] authors are very collegial and supportive [of each other],” Takacs said.

Chicago’s YA scene has grown, according to Takacs. The Book Cellar, which frequently hosts the Forever Young Adult book group, was forced to expand its YA section and separate it from the children’s section as more books were released and requested by readers.

Despite the growing fan base, readers like Chen still face judgment from critics who think the genre is all romantic storylines, and she is too old to read them.

“Maybe they are cultural snobs [who] think everyone should only be reading [Tony] Koltz and Jennifer Eagan,” Chen said. “Guess what? I read them too.”

Nostalgia, diverse characters and literary excellence are all reasons why adult readers pick up YA novels, and ultimately, why they willingly put themselves in the crossfire.

“To cut yourself off from a kind of literature because you think it’s for 14-and 15-year-olds only is to limit your experience of great books,” Chen said. “Why say to an adult ‘You can’t read an award winning book?’ Whether it’s for children or for adolescents—it shouldn’t matter.”