‘Feeling of presence’ demystified

‘Feeling of presence’ demystified

November 17, 2014

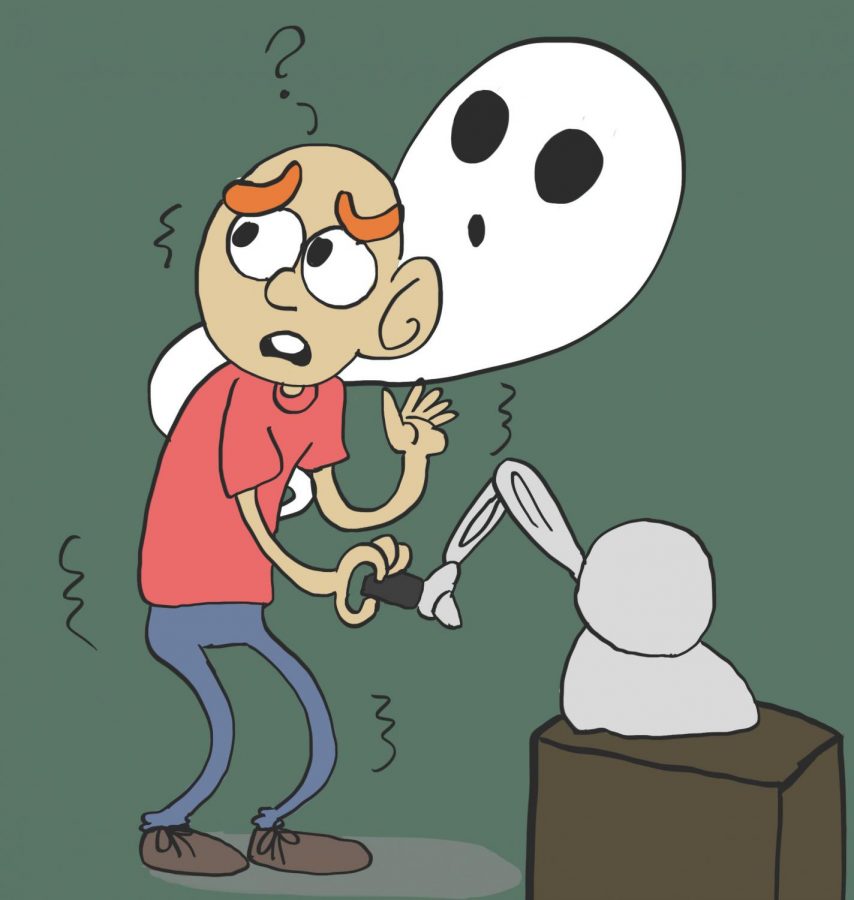

Mountaineers sometimes report the sensation of a nearby presence as they scale great heights, as if someone was right behind them—off to the left or the right a bit—but out of sight. Healthy minds in extreme conditions can generate this ghostly sensation; however, it is more commonly reported in patients diagnosed with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia.

Researchers from École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland used a “master-slave” robotic system to successfully recreate this sensation of an otherworldly apparition in healthy patients in a laboratory. In the study, published online Nov. 6 in the journal Current Biology, blindfolded participants used their index fingers to manipulate a machine in front of them while a robotic arm precisely mimicked their motions on their backs. The robotic interaction took place both in real time and also with a half-second delay. When researchers added the delay, participants reported both the sensation of a physical presence other than their own and a feeling of their bodies drifting forward or backward.

“Participants know there is a robot touching them and that they are the ones controlling the movement,” said Giulio Rognini, Ph. D. and co-author of the study. “The half-second delay is small … but it is sufficient for your brain to not consider these signals—movement and touch—to be generated by you.”

Rognini said the brain generates the experience of being touched by another agent to resolve this cognitive conflict. Whether the dissonance is a result of a psychiatric disorder or induced by the delayed robotic arm, the brain can improperly fold the signals that human senses detect into the experience of being self-aware.

“This [improper integration] is our explanation in trying to account for schizophrenic and psychotic episodes,” Rognini said. “The mismatch between what they predict would happen due to their actions and the actual feedback—this creates the hallucination.”

While the precise neural origin of the feeling of presence, or FoP, is unknown, an analysis performed on the brains of 12 control patients who experienced a pre-existing FoP hallucination identified three brain regions that play a role in contributing to the human perception of having a physical self.

The symptoms of schizophrenia are broken down into two categories: positive and negative, according to Dr. Will Cronenwett, assistant professor at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. Hallucinations are a positive symptom—not because they are good but because they are present in schizophrenic brains and not in normal brains.

Cronenwett said dysfunctions in proprioception—the ability to sense the shape that one’s body is taking in space—could result in the disruption of cognitive networks that impact many brain regions. In all likelihood, people describing an FoP are not experiencing the same phenomena, and it is difficult to attribute symptoms like hallucinations to specific parts of the brain because they generally stem from a more systemic problem, he said.

“The regions in the brain all talk to one another, and when we’re looking at schizophrenia, it’s more likely a widely distributed set of changes that impact neural networks as opposed to saying that it is just localized in one particular region,” Cronenwett said.

The origin of an FoP in healthy individuals may stem from the brain being hindered in the way it monitors and integrates self-generated signals, such as repetitive movements, according to Rognini. A mountain climber may make repetitive movements for a significant length of time in a low-oxygen environment, resulting in the brain’s misattribution of the body’s own signals and the projection of a presence other than oneself. The sensory motor system integrates information the body’s various components perceive with movements to construct a real-time sense of self-awareness.

“We don’t have an exact account of what’s going on [in cases like mountaineers],” Rognini said. “We know that it matches quite well with the phenomenology observed in neurological patients.”

All animals use a system called corollary discharge to distinguish between sensations resulting from their own actions and those that result from external sources, according to Judy Ford, professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco.

“It’s really an ongoing kind of accumulation of information in the brain, millisecond by millisecond,” Ford said. “It’s hard to think of it as proprioception at the first moment that you decide to move, but it probably becomes that by the time you begin to actually get feedback.”

Ford said understanding how people with schizophrenia experience hallucinations is extremely difficult. Some data suggests the symptoms may result more from the activity in the brain preceding an action rather than the response to results of that action, she said.

“In a way, this study shows the lengths the brain goes to in putting together all of the information that contributes to our experience of having one physical body and being separated from the rest of the world,” Rognini said. “When this system is disturbed by brain damage or robotic conflicts, it reveals the multi-representational measure of our selves.”