Hurricanes get blown away

Offshore wind turbines

March 17, 2014

Installing offshore wind turbines in coastal U.S. cities may have benefits beyond reducing air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, a recent study shows.

Mark Jacobson, professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford University, and his team discovered that a large number of offshore wind turbines may be useful in reducing hurricane damage, a finding detailed in a February 2014 study published in Nature.

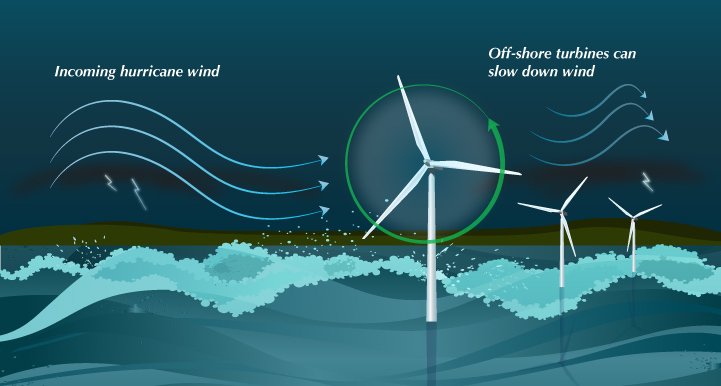

“If you have a large number of wind turbines, it will actually slow down the winds of a hurricane enough to reduce storm damage to coastal cities,” said Willett Kempton, Jacobson’s research partner and research director at the University of Delaware’s Center for Carbon-free Power Integration.

Wind turbines use existing energy found in the air movement and convert it into electricity. Because a hurricane is a large circle of rapidly moving air, when it hits an offshore wind farm, the turbines convert the wind into electricity and slow down the hurricane by reducing wind speeds, according to Kempton.

Cities such as New York City are proposing to build more sea walls that reduce the damage of storm surges. But hurricane protection from offshore wind turbines would come at no extra cost for investors who already plan to install wind farms for electricity, Jacobson said.

Jacobson said if money that is set to be spent on sea walls is instead used for wind turbines, storm damage and wind speed could be reduced and there would be positive investment returns, such as spending less money to repair hurricane damage.

Although the U.S. does not yet have any offshore wind farms, there is offshore wind energy being produced around the world that the U.S. could imitate. The United Kingdom is the world’s most prominent offshore wind energy producer, with more than 22 projects and 1,075 turbines, according to RenewableUK.

Recently, the U.S. took steps toward offshore wind energy with a new $2.6 million project called Cape Wind, located in Horseshoe Shoal near Cape Cod, Mass. The farm is expected to use 130 turbines and is expected to produce up to 420 megawatts of energy, said Cape Wind spokesperson Mark Rodgers said.

“In average wind conditions, it will produce about 75 percent of electricity for that area and help launch a new domestic industry, that of offshore wind,” Rodgers said.

Although wind energy is not the cheapest form of energy in the U.S., Jacobson said the benefits outweigh the cost.

“Right now, it’s more expensive than onshore wind but less expensive than the price of electricity in a lot of places,” Jacobson said. “If you account for the health benefits and the climate benefits, then it will become more attractive, and [if] you start putting them in on a large scale, [the] price will come down significantly.”

With the project supported financially, Cape Wind is expected to finish financing and start construction by the end of this year.

“We feel like there’s no question that 2014 is going to be the year for Cape Wind,” Rodgers said. “It’s going to be the year it’s all going to come together.”

With multiple offshore wind proposals and one project approaching construction, the U.S. may soon see rapid growth in offshore wind energy, Jacobson said.

“There’s no reason it can’t occur rapidly,” Jacobson said. “It’s more of a question of if society decides to do it or not. It’s really a choice the people have to make.”