City’s bright new idea raises pollution concerns

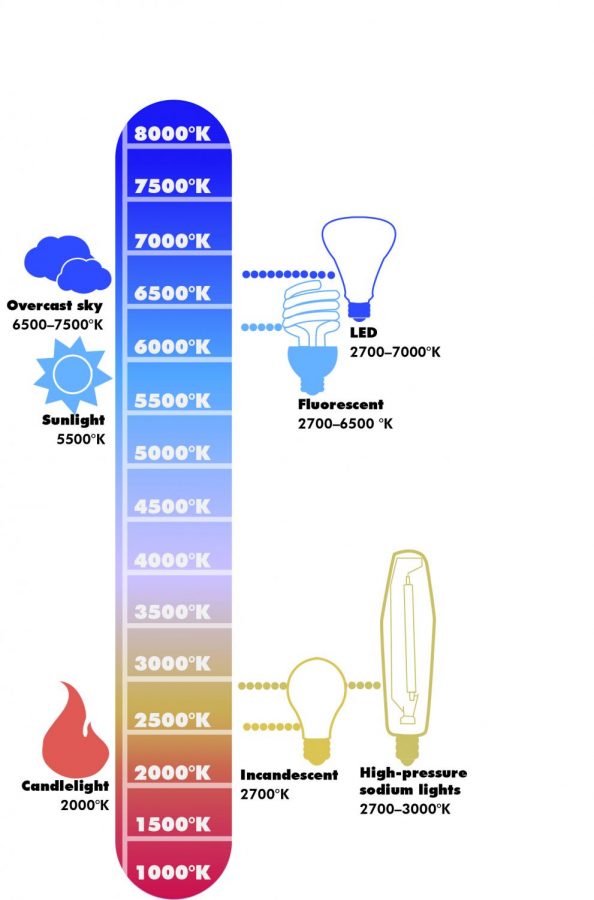

Light sources give off electromagnetic radiation of varying frequencies. When a light source gives off more energy, the color temperature is higher and the wavelength is shorter, resulting in a blue color.

May 2, 2016

Plans to replace 85 percent of Chicago’s high-pressure sodium street lamps with brighter LED lights promise increased energy efficiency, but residents and experts have expressed worries about the project’s potential effects on locals.

The initiative will convert 270,000 of Chicago’s current sodium street lamps into LED fixtures that will consume 50–75 percent less electricity and last three times as long, according to an April 17 City of Chicago press release.

“In 2015, the city’s electricity cost was about $18.5 million for street lighting,” said Michael Claffey, director of public affairs for the Chicago Department of Transportation. “[We] expect to cut that by at least half once the conversion is complete.”

While CDOT reports that LED lights increase energy efficiency, both residents and environmental experts have voiced concerns about possibilities the new fixtures could contribute to light pollution—an excess of artificial light, which has been proven to increase various environmental and health-related concerns.

A 2011 study by the University of Colorado named Chicago the most light-polluted city in the United States.

The LED lights’ color temperature has also been known to contribute to the effects of light pollution. Lights of high color temperatures emit blue light, which is known to contribute to depression and other mood disturbances in humans and animals, according to Alfred Lewy, professor Emeritus of Psychiatry at Oregon Health and Science University and author of the 2006 study “The Circadian Basis of Winter Depression.”

“Scientific thinking on the subject is becoming increasingly clear,” said John Barentine, program manager at the International Dark-Sky Association, a group dedicated to raising awareness about the effects of light pollution. “Exposure to artificial light at night has measurable results in [the] biology of everything on Earth.”

According to Barentine, the human body is regulated by a biological clock that has evolved to respond to natural cycles of light and darkness that occur with the rising and setting of the sun. When these rhythms are disrupted at night by artificial light, depression, obesity, and even diseases such as Type 2 diabetes and certain kinds of cancer can result, he said.

Mike Maerz, a Humboldt Park resident who has worked as a self-employed lighting specialist for 10 years, added that LED lights of a lower color temperature would produce a less disruptive orange glow.

“The LED lighting industry has been working on lowering the color temperature of their lights for a very long time,” he said. “Some of them nail it—other manufacturers don’t. It’s much easier to make the blue LEDs, so that’s what people usually go for.”

In the past, blue LED lights were the more economical choice, but advances in technology have made those with a warmer glow comparable in price, according to Audrey Fischer, president of the Chicago Astronomical Society.

Fischer circulated a petition that requests the newly installed LED lights not exceed 3000K in color temperature, which will prevent them from emitting blue light. The petition also advocates that the lights be placed on motion-sensing dimmers, and the direction of the lighting be carefully controlled to prevent it from spilling into areas where it is not needed.

Many people speculate that Fischer’s insistence on less brightness may counteract safety improvements the renovations hope to achieve, but brighter lighting has not been conclusively proven to reduce crime or traffic safety.

“The Chicago Alley Lighting Project,” an April 2000 study by the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority, found that crime increased by 21 percent in a one-year period when brighter lights were installed in alleyways prone to criminal activity.

It is often assumed that brighter lighting increases safety, but that is not necessarily true, Barentine said. Actually, a well-lit area is easier for perpetrators to navigate.

Referring to traffic safety, Barentine added that increased glare from bright LED lights could make it more difficult for drivers to see.

Residents have also expressed displeasure with the aesthetic qualities of LED lighting.

Grace Grenier, an Avondale resident who said she experiences Seasonal Affective Disorder, a condition that makes individuals’ moods more sensitive to seasonal changes in light levels, expressed concern that the light flowing through her windows at night may increase her depression.

“Even the shadows that are cast by those lights are bizarre,” she said. “It’s like the shadows generated from those lights make everything look fake. It’s like looking at a video game.”

CDOT is willing to accept feedback from residents and comply with the specifications put forth in Fischer’s petition, Claffey said.

“Chicago and other cities are going to move forward on this because the political pressure behind it is too great for them to ignore,” Barentine said. “With that in mind, I think the best outcome would be for the city to slow it down a little bit, even if they want to realize the cost savings immediately.”