Termite-bots building a future

Termite-bots building a future

March 3, 2014

Termites are known for chewing through the foundations of homes and buildings, causing homeowners and renters severe headaches, but the notoriously destructive bugs’ building methods could be the key to new technology used to build large-scale structures.

These wood-eating insects create complex mounds despite working without a set plan or central leader through a technique called swarm intelligence. A new project titled TERMES, created by a group of scientists at Harvard University, uses the termites’ decentralized construction method to build termite-thinking machines capable of building large-scale structures without supervision.

“[Termites] construct these enormous and complicated mounds built by millions of individual insects all acting independently, all with a very limited view of what’s going on, what they react to and what they encounter rather than planning ahead,” said Justin Werfel, research scientist at Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering. “We read about that and we said that’s fantastic. It showed us that it could be done, so we wanted to build and program a swarm of robots to build things using those same principles.”

Werfel and his colleagues, Kirstin Petersen and Radhika Nagpal, published their design Feb. 14 in the journal Science.

The group crafted a design that would use the robots in construction projects that are considered too dangerous for humans to attempt, such as in underwater research, disaster areas and space missions.

“We imagine systems like this can be very useful for building in disaster areas; for instance, building a levy out of sandbags to protect against flooding,” Werfel said. “If you could have a team of robots doing that building for you then you can keep the people out of harm’s way.”

Each robot must have its own sensors programmed with certain “traffic rules” that must be obeyed to create the intended structure. To do this, Werfel created different algorithms using the power of stigmergy, a process in which agents communicate indirectly by sensing the environment around them.

“Rather than having a single brain coordinating the whole process, every robot is independent and decides what to do for itself,” Werfel said. “Each of them has only local information, so with the decentralized reactive approach, it doesn’t matter if some of the robots break, because the rest of them can just carry on and finish the job.”

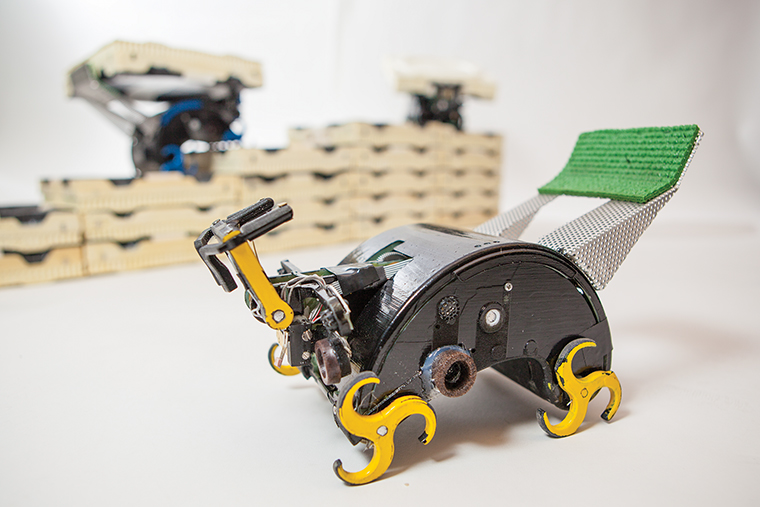

Each robot is about seven inches long and consists of internal metal gears that allow it to move forward, backward, turn in place and climb up and down elevated surfaces.

The robots are intended to be minimalist structures and have four types of sensors, Petersen said. Each one has a pattern recognition system that includes a 6 pixel camera, which allows the robot to observe its location on the structure as it moves; an accelerometer to sense tilt, allowing it to know when to climb up or down; and five ultrasound sonar units to help the robots circle around a structure and detect other robots by sending out a low-volume alarm signal.

“The field of manipulation is complicated and the field of maneuvering is complicated and no one has ever really tried to combine the two into something that works reliably over a long sequence of steps and certainly not something that can actually build structures larger than themselves,” Petersen said. “It’s a proof of concept that we can do that and that we can do it very simply with onboard sensing.”

In one of the demonstrations, one termite-thinking robot was programmed to build a 10-brick staircase 18 times the robot’s volume in 45 minutes, according to Petersen.

While swarm robotics has been around for the past 15 years, the TERMES project is a promising step in taking the technology from the lab to real world scenarios because the researchers have the robots performing complex tasks based on simple guidelines, said Matthew Spenko, associate professor of mechanical engineering at the Illinois Institute of Technology.

“I think what’s interesting about the Harvard project is the fact that they are using multiple robots to do small tasks to create one large task,” Spenko said.

Although the group was able to create a “proof of concept,” establishing viability, the robots have not yet been used outside the lab.

Spenko said some obstacles researchers face in implementing the robots stem from working with robots in controlled settings, such as laboratories, rather than testing them in real world applications, where scenarios are unpredictable.

“Once we see that breakthrough, we’ll start seeing some swarms, but it’s definitely there and possible,” Spenko said. “I don’t think it’s in the five-year horizon. I think it’s a little bit further off than that.”

Looking ahead, the group said it hopes the idea will inspire robots that could build more complicated structures, such as overhangs or bridges, Petersen said.

“The idea has never been to replace human construction workers, but to replace construction workers where it’s hard and dangerous for them to work,” Petersen said.