Graphic cigarette warning labels reduce smoking rates

Cigarettes

November 24, 2014

In an effort to reduce cigarette consumption, Canada became the first country to mandate graphic warning labels depicting the negative effects of smoking on cigarette packaging in 2001. Since then, the country has seen a reduction in smoking rates by 12.1–19.6 percent, according to a November 2013 report published in the journal Tobacco Control.

Nearly 80 countries have now followed suit and implemented pictorial warning labels on cigarette packaging and have seen similar results, according to a September 2014 report from the Canadian Cancer Society. However, the U.S. has yet to do the same.

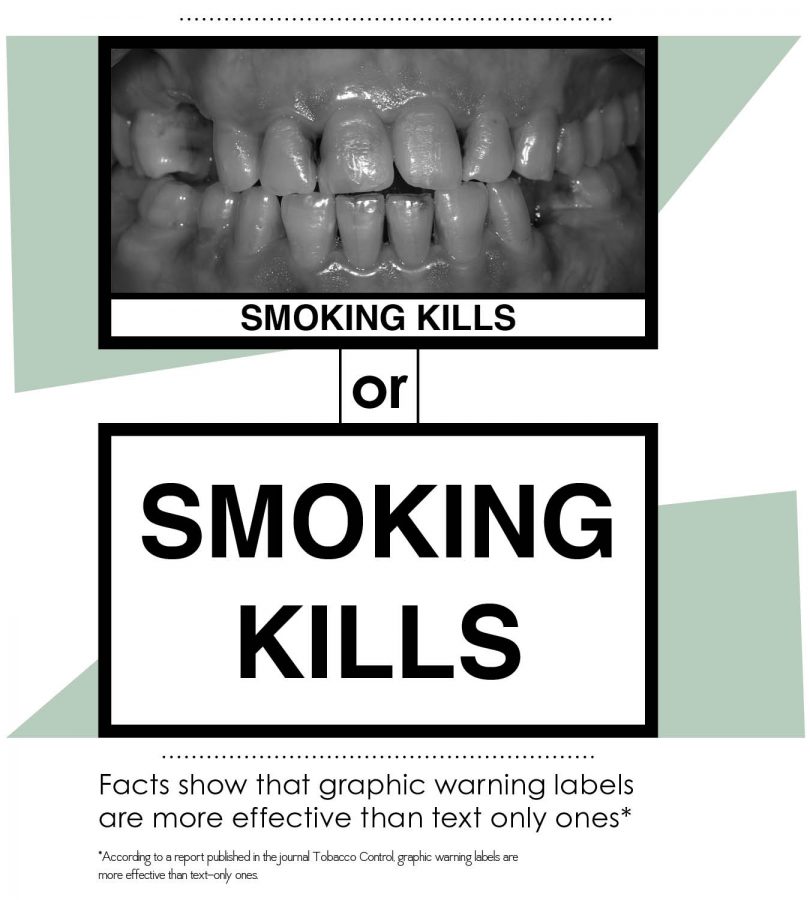

According to a March 2014 study published in the journal Health Communication, graphic cigarette warning labels were found to be more effective than text-only warning labels among a population of college students.

The study exposed a population of non-smoking college students to a series of cigarette warning labels differing in certain features, according to Xiaoli Nan, an author of the study and an associate professor in the Department of Communications at the University of Maryland. The researchers compared the effectiveness of graphic warning labels to text-only ones; “loss-framed” labels focusing on the negative impacts of smoking to “gain-framed” ones highlighting the positive consequences of refraining from smoking; and present-oriented ones showing the short-term effects of smoking versus future-oriented ones that focused on the long-term effects of smoking.

Typically, these types of studies would focus on a population of smokers, but Nan said they focused on college non-smokers to evaluate if graphic warning labels could have any deterring factors that would discourage non-smokers from picking up the habit.

“Smoking is addictive, and it’s hard to persuade people to stop smoking,” Nan said. “But it might be easier to persuade people not to start smoking in the first place.”

The study also found that loss-framed warning labels were perceived as more effective than gain-framed ones, but there was no significant difference between the perceived effectiveness of present- versus future-oriented labels.

According to Laurent Huber, executive director of Action on Smoking and Health, the Food and Drug Administration proposed that the U.S. should require graphic warning labels on all cigarette packaging, but the measure was quickly shut down by lobbying efforts from the tobacco industry.

“If those interventions were useless, the tobacco industry would not oppose them,” Huber said. “They immediately filed a suit because this is clearly an effective strategy.”

Huber said implementing graphic warning labels is cost-effective for the government because it could spend less on other anti-smoking interventions and the tobacco industry would be responsible for the printing costs of the labels.

Huber said while the implementation of graphic warning labels on cigarette packaging could have economic effects, it would not bankrupt the industry.

Erika Sward, assistant vice president for National Advocacy at the American Lung Association, said the health benefits of the graphic warning labels are the main concern, not the financial impact they could have on tobacco companies.

“It could have a significant impact on public health, and that’s what ultimately we are aggressively pushing for,” Sward said.

In 2009, Congress passed the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, which mandated that the FDA require all cigarette packages and advertisements to contain graphic warning labels. Published in June 2011, the FDA’s final rule on the issue required that colored graphic warnings cover 50 percent of the front and back of all cigarette packages and 20 percent of all cigarette advertisements. Shortly after, several tobacco manufacturers filed suit in the U.S. District Court challenging the regulation, and the court ruled the graphic warning labels unconstitutionally limited the tobacco companies’ right to freedom of speech.

Many countries have taken the health warnings a step further in addition to a large graphic warning, requiring all cigarette packages to follow a standard packaging with no brand logos or colors to make smoking seem less appealing Huber said.

“The current cigarette warning labels in the U.S. have not been updated since 1984,” Sward said. “They have been long-ago proven to be highly ineffective, and so it’s very important that the FDA and the U.S. do what so many other countries have done, which is to require graphic warning labels on cigarette packages to reduce smoking rates.”