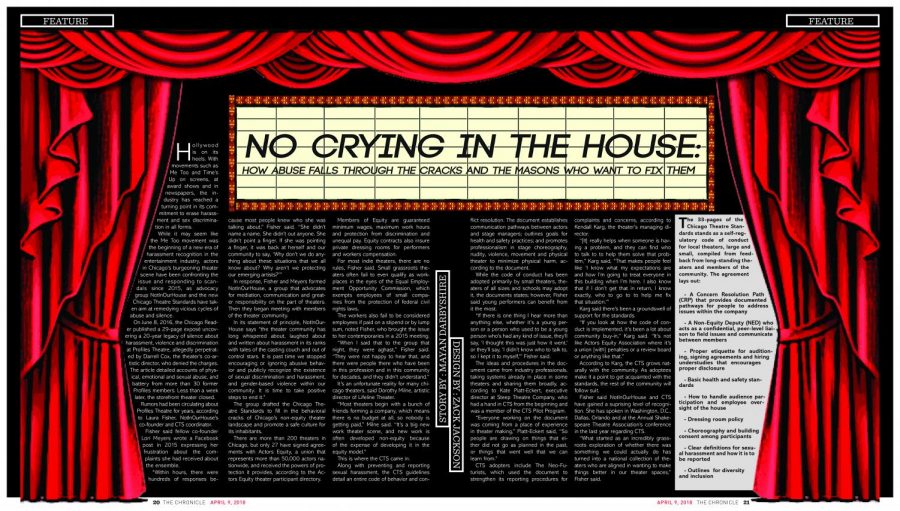

No Crying In the House: How Abuse Falls Through The Cracks and the Masons Who Want to Fix It

No Crying In the House

April 9, 2018

Hollywood is on its heels. With movements such as Me Too and Time’s Up on screens, at award shows and in newspapers, the industry has reached a turning point in its commitment to erase harassment and sex discrimination in all forms.

While it may seem like the Me Too movement was the beginning of a new era of harassment recognition in the entertainment industry, actors in Chicago’s burgeoning theater scene have been confronting the issue and responding to scandals since 2015, as advocacy group NotInOurHouse and the new Chicago Theatre Standards have taken aim at remedying vicious cycles of abuse and silence.

On June 8, 2016, the Chicago Reader published a 29-page exposé uncovering a 20-year legacy of silence about harassment, violence and discrimination at Profiles Theatre, allegedly perpetrated by Darrell Cox, the theater’s co-artistic director, who denied the charges. The article detailed accounts of physical, emotional and sexual abuse, and battery from more than 30 former Profiles members. Less than a week later, the storefront theater closed.

Rumors had been circulating about Profiles Theatre for years, according to Laura Fisher, NotInOurHouse’s co-founder and CTS coordinator.

Fisher said fellow co-founder Lori Meyers wrote a Facebook post in 2015 expressing her frustration about the complaints she had received about the ensemble.

“Within hours, there were hundreds of responses because most people knew who she was talking about,” Fisher said. “She didn’t name a name. She didn’t out anyone. She didn’t point a finger. If she was pointing a finger, it was back at herself and our community to say, ‘Why don’t we do anything about these situations that we all know about? Why aren’t we protecting our emerging artists?’”

In response, Fisher and Meyers formed NotInOurHouse, a group that advocates for mediation, communication and greater responsibility on the part of theaters. Then they began meeting with members of the theater community.

In its statement of principle, NotInOurHouse says “the theater community has long whispered about, laughed about and written about harassment in its ranks with tales of the casting couch and out of control stars. It is past time we stopped encouraging or ignoring abusive behavior and publicly recognize the existence of sexual discrimination and harassment, and gender-based violence within our community. It is time to take positive steps to end it.”

The group drafted the Chicago Theatre Standards to fill in the behavioral cracks of Chicago’s non-equity theater landscape and promote a safe culture for its inhabitants.

There are more than 200 theaters in Chicago, but only 27 have signed agreements with Actors Equity, a union that represents more than 50,000 actors nationwide, and received the powers of protection it provides, according to the Actors Equity theater participant directory.

Members of Equity are guaranteed minimum wages, maximum work hours and protection from discrimination and unequal pay. Equity contracts also insure private dressing rooms for performers and workers compensation.

For most indie theaters, there are no rules, Fisher said. Small grassroots theaters often fail to even qualify as workplaces in the eyes of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which exempts employees of small companies from the protection of federal civil rights laws.

The workers also fail to be considered employees if paid on a stipend or by lump sum, noted Fisher, who brought the issue to her contemporaries in a 2015 meeting.

“When I said that to the group that night, they were aghast,” Fisher said. “They were not happy to hear that, and there were people there who have been in this profession and in this community for decades, and they didn’t understand.”

It’s an unfortunate reality for many chicago theaters, said Dorothy Milne, artistic director of Lifeline Theater.

“Most theaters begin with a bunch of friends forming a company, which means there is no budget at all, so nobody is getting paid,” Milne said. “It’s a big new work theater scene, and new work is often developed non-equity because of the expense of developing it in the equity model.”

This is where the CTS came in.

Along with preventing and reporting sexual harassment, the CTS guidelines detail an entire code of behavior and conflict resolution. The document establishes communication pathways between actors and stage managers; outlines goals for health and safety practices; and promotes professionalism in stage choreography, nudity, violence, movement and physical theater to minimize physical harm, according to the document.

While the code of conduct has been adopted primarily by small theaters, theaters of all sizes and schools may adopt it, the documents states; however, Fisher said young performers can benefit from it the most.

“If there is one thing I hear more than anything else, whether it’s a young person or a person who used to be a young person who’s had any kind of issue, they’ll say, ‘I thought this was just how it went,’ or they’ll say, ‘I didn’t know who to talk to, so I kept it to myself,’” Fisher said.

The ideas and procedures in the document came from industry professionals, taking systems already in place in some theaters and sharing them broadly, according to Kate Piatt-Eckert, executive director at Steep Theatre Company, who had a hand in CTS from the beginning and was a member of the CTS Pilot Program.

“Everyone working on the document was coming from a place of experience in theater making,” Piatt-Eckert said, “So people are drawing on things that either did not go as planned in the past, or things that went well that we can learn from.”

CTS adopters include The Neo-Futurists, which used the document to strengthen its reporting procedures for complaints and concerns, according to Kendall Karg, the theater’s managing director.

“[It] really helps when someone is having a problem, and they can find who to talk to to help them solve that problem,” Karg said, “That makes people feel like ‘I know what my expectations are and how I’m going to treat everyone in this building when I’m here. I also know that if I don’t get that in return, I know exactly, who to go to to help me fix that situation.’”

Karg said there’s been a groundswell of support for the standards.

“If you look at how the code of conduct is implemented, it’s been a lot about community buy-in,” Karg said. “It’s not like Actors Equity Association where it’s a union [with] penalties or a review board or anything like that.”

According to Karg, the CTS grows naturally with the community. As adoptees make it a point to get acquainted with the standards, the rest of the community will follow suit.

Fisher said NotInOurHouse and CTS have gained a suprising level of recognition. She has spoken in Washington, D.C., Dallas, Orlando and at the Annual Shakespeare Theatre Association’s conference in the last year regarding CTS.

“What started as an incredibly grassroots exploration of whether there was something we could actually do has turned into a national collection of theaters who are aligned in wanting to make things better in our theater spaces,” Fisher said.