Natural Tendencies: Critical Encounters’ personal narratives on Human/Nature

October 13, 2008

Renewed interest in forests, as diverse repositories of medicines, pits pharmaceutical companies against large scale agribusiness, small slash farming, grazing and various housing development enterprises. The forests have emerged as a fiercely contested space, at the same time they are in danger of disappearing.

The growing representation of this state of affairs is a reminder to me about how integral the forest has been to my family. For generations, we Baileys have known how to harvest the fruits of the forest. As far back as I can remember, members of my family have told stories about the forest as a source of food, fuel and a powerful place residing at the borders of reality and imagination.

During the first eight years of my life, my family lived an agrarian existence. My father was a sharecropper in northern Alabama, and we lived in a dog-trot house overlooking vast cotton fields that backed up against great dark woods.

During this time, the nature of the forest was revealed to me. My mother and father taught me several lessons about the power of the forest, but it was my grandmother who provided with me deep and compelling knowledge, comprehension and applications about the relationships of the woods to the lives of real people.

Later in my life, I came to know the work of a Native American woman whose studies in ethno-botany served to remind me of how fortunate I’d been to understand, with such deep reverence, the force and the power of the forest.

My mother loved the woods, but not so much at night. Her love of it came from stories and memories of my grandmother going into the woods both day and night to get tree bark, fungi, plant leaves, seeds, roots and flowers to make medicine.

My mother’s fears of the woods were generated by the unexplained and heartbreaking death of her brother while hunting with young men late at night. Her fears also stemmed from bad dreams of loved ones, real and imagined, lost in the woods and never to be heard from again. My mother loved to pick blackberries at the edge of the woods.

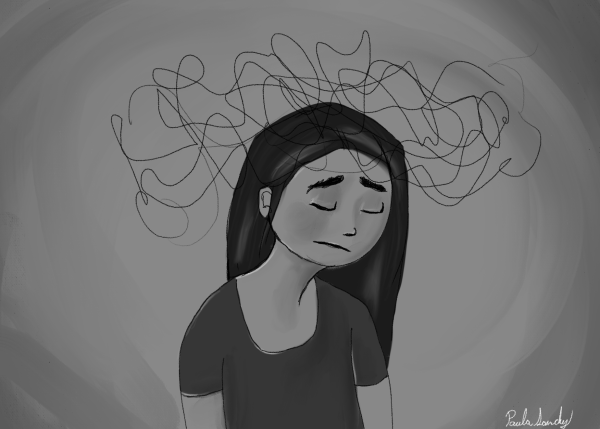

She loved the daytime forest paths too, and she had her favorite ones. She loved the woods most when winter left and spring leapt into summer, when the world around her sprouted and dressed itself in different shades of green. She knew something potent and awful lived there. So real were her fears that sometimes when she saw its smooth, green outline against the sky, she’d turn away or lower her eyes.

My father loved the woods, period. He knew the best fishing places, too-calm, resonant places where little waterfalls spilled into deep green pools and splashed over glistening rocks. He knew all the paths through the woods. He knew which trees opossums would likely live in, and he knew where to put his feet so he wouldn’t disturb snakes and be bitten by them.

He had tramped through the woods most of his life. He felt comfortable with all the scary things, crawling about the woods, especially at night. He had slept in the woods during a rainstorm and had lived with all the creepy wet things that crawl and slither across the ground in the woods. He gathered nuts and wood for the saw mill and stove. He saw the woods as an endless resource for his needs.

It was my grandmother who connected me on the deepest level with the forest. I’d see her go out into the woods on moon-bright nights with a lantern, flower basket and small cutting tools. She was often called to the bedside of sick people, and she carried a box of medicines she’d made from forest materials.

Grandma once told me that the life of the woods is willed into being by something larger than what people can imagine. She described a lovely system-a place of sunlight and gloom.

Horror and delight dwell there in equal portions, side-by-side in familiar unease as old as time itself. She said we carry the deep, old-life memories of that uneasiness alive at the boundary where our dreams and realities intersect.

In our minds, we wish the forest alive. We empower it with our hopes and fears. Our fears reinvigorate and rekindle the moment when wonder and dread leaped elementally from the first sparks of cracked stones and wood, into the minds of the first people in a forest somewhere halfway around the world.

In 1979, I taught a course at Columbia entitled Oral Traditions and Writing in America.

The course explored the oral traditions of both folk and contemporary urban cultures. During that fall semester, I invited an ethno-botanist by the name of Keewaydinoquay Pascal, who wrote Woman of the Northwest Wind, to be a guest speaker in my class.

She had gained a following at the Newberry Library in Chicago by telling stories of the Ojibwa Indian culture. A year earlier, the Botanical Museum of Harvard University published her book Puhpohwee for the People: A Narrative Account of Some Uses of Fungi among the Ahnishinaubeg. Her interest in ethno-mycological studies and her knowledge of the forest reminded me of my grandmother. They spoke a similar language.

From my grandmother, mother, father and Keewaydon, I learned that the woods are alive, possess their own rhythm and keep their own sense of time. It gives up its secrets grudgingly. One must discover it to hear it whisper and sing.

Despite my fears of the forests, I continue to invite the woods to create within me feelings of home and well-being.

The aim of “Natural Tendencies” is to show the relationships between humans and nature, as well as to better understand human nature. This is the third edition of Critical Encounters.

If you would like to submit to Human “Natural Tendencies,” please contact Kevin Fuller at (312) 369-8505 or kgfuller@colum.edu.