Talking in tongues: Science suggests Neanderthals spoke in more than grunts

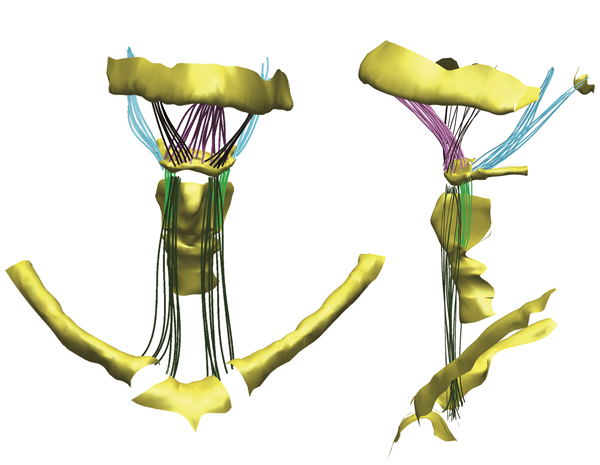

A 3D rendering of a human hyoid bone

March 17, 2014

Evidence suggests Neanderthals fashioned primitive tools and weapons, buried their dead, controlled fires and used dyes—but new research shows these tasks may not have been carried out in silence.

Analysis of a 60,000-year-old Neanderthal hyoid bone, which supports the tongue and allows humans to speak, has anthropologists considering the possibility that the Homo sapiens’ genetic brethren were not only communicators, but developed some level of complex speech.

“When this hyoid was first found it was described as basically indistinguishable from what you’d see in modern humans,” said Stephen Wroe, a paleontologist and director of the Computational Biomechanics Research Group at the University of New England in Australia.

Wroe, who co-authored a December 2013 study published in Public Library of Science One, and his team generated a high-resolution 3D computer model of both the Neanderthal hyoid and a modern human sample. Though this Neanderthal hyoid bone was unearthed in 1989, the computing power required to direct the X-ray and make comparisons between the two species has only recently become available, Wroe said.

In both Neanderthal and modern human physiology, the hyoid connects to the tongue and various parts of the vocal tract. It acts as an anchor to the tongue muscle and surrounding connective tissues, which allows humans to swallow and perform a wide range of throat movements.

The micro-detail rendered from the Neanderthal hyoid revealed that it was very similar to a modern human’s, further suggesting that some level of speech was used by Neanderthals, Wroe said.

“If this bone was being used in a very different way, we’d expect to see that reflected in the mechanical behavior shown through this imaging,” Wroe said. “[The data] undermines the argument that Neanderthals and modern humans did not use this bone in the same way.”

Though the data from the study suggests an almost equivalent usage of the speech-related hyoid bone in Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, it cannot be said with absolute certainty that they were conversing, according to John Hawks, associate professor in anthropology at the University of Wisconsin.

“It’s difficult for anthropologists to look at data and say concretely, ‘Yes, that’s what they were doing,’” Hawks said.

Scientists have a history of interpreting Neanderthal behavior in the least flattering manner, Hawks said, adding that he frames the Neanderthals’ language use in terms of whether or not it is possible for humans to live in speechless groups. The way Neanderthals used their throats appeared to be indistinguishable from modern humans, Hawks said.

Anthropologists still do not know what it takes to construct a language, Hawks said. Although this new data is concrete evidence that Neanderthals had the tools for speech, it does not mean they constructed languages.

Hawks said he thinks the wide dispersement of the Neanderthal population around the world could explain the genetic changes associated with language usage.

“We know [Neanderthals] were capable of doing very interesting things, but they didn’t do those interesting things as often as some later populations did,” Hawks said.

Because Neanderthals lived in lower density groups than modern humans during the same time period, it was unnecessary for them to communicate with unfamiliar people they encountered, Hawks said.

“We can assume they’re just like [today’s] humans, or we try to come up with a scenario where they’re not like [us] but have the same kind of throat structure,” Hawks said.

Scientists do, however, have the ability to make some inferences about Neanderthal behavior based on their actions that have been studied.

According to David Frayer, a professor emeritus of paleoanthropology at the University of Kansas, handedness—the tendency to use either the left hand or right hand more than the other—in Neanderthals can be determined the same way as our handedness.

Furthermore, Hawks said asymmetry is seen in the frontal portion of the Neanderthal brain—the same location as modern humans’ asymmetry related to language.

Frayer said he finds it hard to imagine the Neanderthals doing activities without using a language.

“I think it all fits together,” Frayer said. “Neanderthals could have been talking just like us.”