Crowdfunding Crayons: Teachers get creative to provide for students

Crowdfunding Crayons: Teachers get creative to provide for students

October 10, 2016

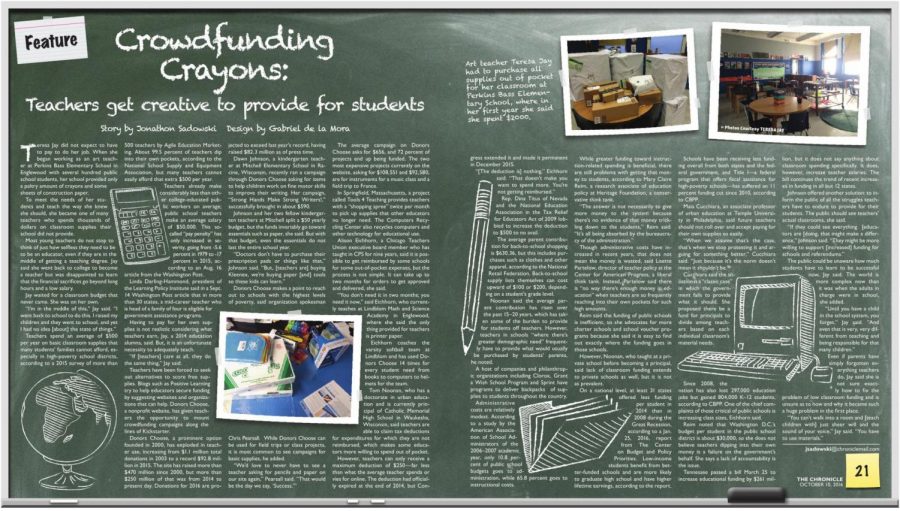

Teresa Jay did not expect to have to pay to do her job. When she began working as an art teacher at Perkins Bass Elementary School in Englewood with several hundred public school students, her school provided only a paltry amount of crayons and some sheets of construction paper.

To meet the needs of her students and teach the way she knew she should, she became one of many teachers who spends thousands of dollars on classroom supplies their school did not provide.

Most young teachers do not stop to think of just how selfless they need to be to be an educator, even if they are in the middle of getting a teaching degree. Jay said she went back to college to become a teacher but was disappointed to learn that the financial sacrifices go beyond long hours and a low salary.

Jay waited for a classroom budget that never came. She was on her own.

“I’m in the middle of this,” Jay said. “I went back to school to do this. I raised my children and they went to school, and yet I had no idea [about] the state of things.”

Teachers spend an average of $500 per year on basic classroom supplies that many students’ families cannot afford, especially in high-poverty school districts, according to a 2015 survey of more than 500 teachers by Agile Education Marketing. About 99.5 percent of teachers dip into their own pockets, according to the National School Supply and Equipment Association, but many teachers cannot easily afford that extra $500 per year.

Teachers already make considerably less than other college-educated public workers on average; public school teachers make an average salary of $50,000. This so-called “pay penalty” has only increased in severity, going from -5.6 percent in 1979 to -17 percent in 2015, according to an Aug. 16 article from the Washington Post.

Linda Darling-Hammond, president of the Learning Policy Institute said in a Sept. 14 Washington Post article that in more than 30 states, a mid-career teacher who is head of a family of four is eligible for government assistance programs.

Having to pay for her own supplies is not realistic considering what teachers earn, Jay, a 2014 education alumna, said. But, it is an unfortunate necessity to adequately teach.

“If [teachers] care at all, they do the same thing,” Jay said.

Teachers have been forced to seek out alternatives to score free supplies. Blogs such as Positive Learning try to help educators secure funding by suggesting websites and organizations that can help. Donors Choose, a nonprofit website, has given teachers the opportunity to mount crowdfunding campaigns along the lines of Kickstarter.

Donors Choose, a prominent option founded in 2000, has exploded in teacher use, increasing from $1.1 million total donations in 2003 to a record $92.8 million in 2015. The site has raised more than $470 million since 2000, but more than $250 million of that was from 2014 to present day. Donations for 2016 are projected to exceed last year’s record, having raised $82.3 million as of press time.

Dawn Johnson, a kindergarten teacher at Mitchell Elementary School in Racine, Wisconsin, recently ran a campaign through Donors Choose asking for items to help children work on fine motor skills to improve their writing. Her campaign, “Strong Hands Make Strong Writers!,” successfully brought in about $590.

Johnson and her two fellow kindergarten teachers at Mitchell split a $50 yearly budget, but the funds invariably go toward essentials such as paper, she said. But with that budget, even the essentials do not last the entire school year.

“Doctors don’t have to purchase their prescription pads or things like that,” Johnson said. “But, [teachers are] buying Kleenex, we’re buying paper [and] tools so these kids can learn.”

Donors Choose makes a point to reach out to schools with the highest levels

of poverty, said organization spokesman Chris Pearsall. While Donors Choose can be used for field trips or class projects, it is most common to see campaigns for basic supplies, he added.

“We’d love to never have to see a teacher asking for pencils and paper on our site again,” Pearsall said. “That would be the day we say, ‘Success.’”

The average campaign on Donors Choose asks for $656, and 72 percent of projects end up being funded. The two most expensive projects currently on the website, asking for $108,551 and $92,580, are for instruments for a music class and a field trip to France.

In Springfield, Massachusetts, a project called Tools 4 Teaching provides teachers with a “shopping spree” twice per month to pick up supplies that other educators no longer need. The Computers Recycling Center also recycles computers and other technology for educational use.

Alison Eichhorn, a Chicago Teachers Union executive board member who has taught in CPS for nine years, said it is possible to get reimbursed by some schools for some out-of-pocket expenses, but the process is not simple. It can take up to two months for orders to get approved and delivered, she said.

“You don’t need it in two months; you need it now,” said Eichhorn, who currently teaches at Lindblom Math and Science Academy in Englewood, where she said the only thing provided for teachers is printer paper.

Eichhorn coaches the varsity softball team at Lindblom and has used Donors Choose 14 times for every student need from books to computers to helmets for the team.

Tom Noonan, who has a doctorate in urban education and is currently principal of Catholic Memorial High School in Waukesha, Wisconsin, said teachers are able to claim tax deductions for expenditures for which they are not reimbursed, which makes some educators more willing to spend out of pocket.

However, teachers can only receive a maximum deduction of $250—far less than what the average teacher spends or vies for online. The deduction had officially expired at the end of 2014, but Congress extended it and made it permanent in December 2015.

“[The deduction is] nothing,” Eichhorn said. “That doesn’t make you want to spend more. You’re not getting reimbursed.”

Rep. Dina Titus of Nevada and the National Education Association in the Tax Relief for Educators Act of 2009 lobbied to increase the deduction to $500 to no avail.

The average parent contribution for back-to-school shopping is $630.36, but this includes purchases such as clothes and other apparel, according to the National Retail Federation. Back-to-school supply lists themselves can cost upward of $100 or $200, depending on a student’s grade level.

Noonan said the average parent contribution has risen over

the past 15–20 years, which has taken some of the burden to provide for students off teachers. However, teachers in schools “where there’s greater demographic need” frequently have to provide what would usually

be purchased by students’ parents, he noted.

A host of companies and philanthropic organizations including Clorox, Grant a Wish School Program and Sprint have programs to deliver backpacks of supplies to students throughout the country.

Administrative costs are relatively modest. According to a study by the American Association of School Administrators of the 2006–2007 academic year, only 10.8 percent of public school budgets goes to administration, while 65.8 percent goes to instructional costs.

While greater funding toward instruction-related spending is beneficial, there are still problems with getting that money to students, according to Mary Claire Reim, a research associate of education policy at Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank.

“The answer is not necessarily to give more money to the system because there’s no evidence of that money trickling down to the students,” Reim said. “It’s all being absorbed by the bureaucracy of the administration.”

Though administrative costs have increased in recent years, that does not mean the money is wasted, said Lisette Partelow, director of teacher policy at the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank. Instead, Partelow said there is “no way there’s enough money in education” when teachers are so frequently reaching into their own pockets for such high amounts.

Reim said the funding of public schools is inefficient, so she advocates for more charter schools and school voucher programs because she said it is easy to find out exactly where the funding goes in those schools.

However, Noonan, who taught at a private school before becoming a principal, said lack of classroom funding extends to private schools as well, but it is not

as prevalent.

On a national level, at least 31 states offered less funding per student in 2014 than in 2008 during the Great Recession, according to a Jan. 25, 2016, report from The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Low-income students benefit from better-funded schools and are more likely to graduate high school and have higher lifetime earnings, according to the report.

Schools have been receiving less funding overall from both states and the federal government, and Title I—a federal program that offers fiscal assistance for high-poverty schools—has suffered an 11 percent funding cut since 2010, according to CBPP.

Maia Cucchiara, an associate professor of urban education at Temple University in Philadelphia, said future teachers should not roll over and accept paying for their own supplies so easily.

“When we assume that’s the case, that’s when we stop protesting it and arguing for something better,” Cucchiara said. “Just because it’s the norm doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be.”

Cucchiara said the situation is a “classic case” in which the government fails to provide what it should. She proposed there be a fund for principals to divide among teachers based on each individual classroom’s material needs.

Since 2008, the nation has also lost 297,000 education jobs but gained 804,000 K–12 students, according to CBPP. One of the chief complaints of those critical of public schools is increasing class sizes, Eichhorn said.

Reim noted that Washington D.C.’s budget per student in the public school district is about $30,000, so she does not believe teachers dipping into their own money is a failure on the government’s behalf. She says a lack of accountability is the issue.

Tennessee passed a bill March 25 to increase educational funding by $261 million, but it does not say anything about classroom spending specifically. It does, however, increase teacher salaries. The bill continues the trend of recent increases in funding in all but 12 states.

Johnson offered another solution: to inform the public of all the struggles teachers have to endure to provide for their students. The public should see teachers’ actual classrooms, she said.

“If they could see everything [educators are [doing, that might make a difference,” Johnson said. “They might be more willing to support [increased] funding for schools and referendums.”

The public could be unaware how much students have to learn to be successful now, Jay said. The world is more complex now than it was when the adults in charge were in school, she added.

“Until you have a child in the school system, you forget,” Jay said. “And even that is very, very different from teaching and being responsible for that many children.”

Even if parents have simply forgotten everything teachers do, Jay said she is not sure exactly how to fix the problem of low classroom funding and is unsure as to how and why it became such a huge problem in the first place.

“You can’t walk into a room and [teach children with] just sheer will and the sound of your voice,” Jay said. “You have to use materials.”