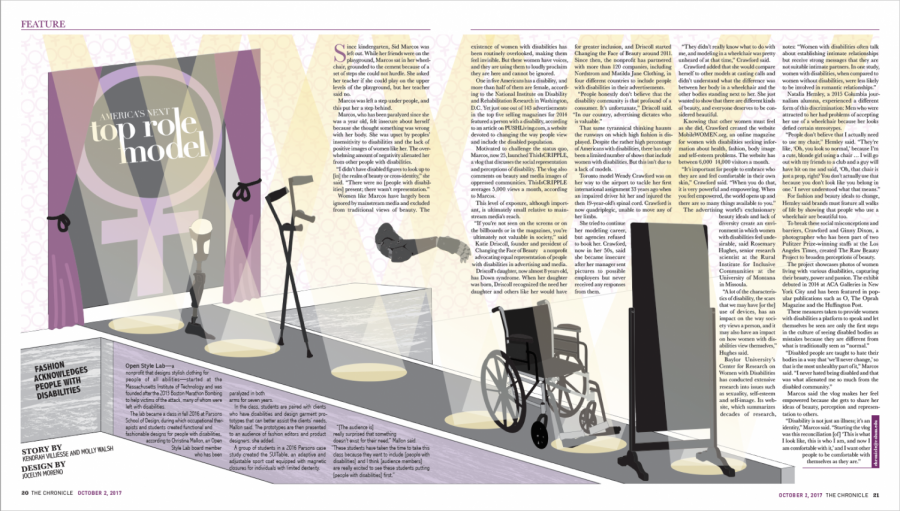

America’s Next Top Role Model

America’s Next Top Role Model

October 2, 2017

Since kindergarten, Sid Marcos was left out. While her friends were on the playground, Marcos sat in her wheelchair, grounded to the cement because of a set of steps she could not hurdle. She asked her teacher if she could play on the upper levels of the playground, but her teacher said no.

Marcos was left a step under people, and this put her a step behind.

Marcos, who has been paralyzed since she was a year old, felt insecure about herself because she thought something was wrong with her body. She was upset by peoples’ insensitivity to disabilities and the lack of positive images of women like her. The overwhelming amount of negativity alienated her from other people with disabilities.

“I didn’t have disabled figures to look up to [in] the realm of beauty or cross-identity,” she said. “There were no [people with disabilities] present; there wasn’t representation.”

Women like Marcos have largely been ignored by mainstream media and excluded from traditional views of beauty. The existence of women with disabilities has been routinely overlooked, making them feel invisible. But these women have voices, and they are using them to loudly proclaim they are here and cannot be ignored.

One in five Americans has a disability, and more than half of them are female, according to the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research in Washington, D.C. Yet just one out of 143 advertisements in the top five selling magazines for 2014 featured a person with a disability, according to an article on PUSHLiving.com, a website devoted to changing the way people view and include the disabled population.

Motivated to challenge the status quo, Marcos, now 25, launched ThisIsCRIPPLE, a vlog that discusses the social representation and perceptions of disability. The vlog also comments on beauty and media images of oppressed communities. ThisIsCRIPPLE averages 5,000 views a month, according to Marcos.

This level of exposure, although important, is ultimately small relative to mainstream media’s reach.

“If you’re not seen on the screens or on the billboards or in the magazines, you’re ultimately not valuable in society,” said Katie Driscoll, founder and president of Changing the Face of Beauty—a nonprofit advocating equal representation of people with disabilities in advertising and media.

Driscoll’s daughter, now almost 8 years old, has Down syndrome. When her daughter was born, Driscoll recognized the need her daughter and others like her would have for greater inclusion, and Driscoll started Changing the Face of Beauty around 2011. Since then, the nonprofit has partnered with more than 120 companies, including Nordstrom and Matilda Jane Clothing, in four different countries to include people with disabilities in their advertisements.

“People honestly don’t believe that the disability community is that profound of a consumer. It’s unfortunate,” Driscoll said. “In our country, advertising dictates who is valuable.”

That same tyrannical thinking haunts the runways on which high fashion is displayed. Despite the rather high percentage of Americans with disabilities, there has only been a limited number of shows that include women with disabilities. But this isn’t due to a lack of models.

Toronto model Wendy Crawford was on her way to the airport to tackle her first international assignment 33 years ago when an impaired driver hit her and injured the then 19-year-old’s spinal cord. Crawford is now quadriplegic, unable to move any of her limbs.

She tried to continue her modeling career, but agencies refused to book her. Crawford, now in her 50s, said she became insecure after her manager sent pictures to possible employers but never received any responses from them.

“They didn’t really know what to do with me, and modeling in a wheelchair was pretty unheard of at that time,” Crawford said.

Crawford added that she would compare herself to other models at casting calls and didn’t understand what the difference was between her body in a wheelchair and the other bodies standing next to her. She just wanted to show that there are different kinds of beauty, and everyone deserves to be considered beautiful.

Knowing that other women must feel as she did, Crawford created the website MobileWOMEN.org, an online magazine for women with disabilities seeking information about health, fashion, body image and self-esteem problems. The website has between 6,000–14,000 visitors a month.

“It’s important for people to embrace who they are and feel comfortable in their own skin,” Crawford said. “When you do that, it is very powerful and empowering. When you feel empowered, the world opens up and there are so many things available to you.”

The advertising world’s exclusionary beauty ideals and lack of diversity create an environment in which women with disabilities feel undesirable, said Rosemary Hughes, senior research scientist at the Rural Institute for Inclusive Communities at the University of Montana in Missoula.

“A lot of the characteristics of disability, the scars that we may have [or the] use of devices, has an impact on the way society views a person, and it may also have an impact on how women with disabilities view themselves,” Hughes said.

Baylor University’s Center for Research on Women with Disabilities has conducted extensive research into issues such as sexuality, self-esteem and self-image. Its website, which summarizes decades of research, notes: “Women with disabilities often talk about establishing intimate relationships but receive strong messages that they are not suitable intimate partners. In one study, women with disabilities, when compared to women without disabilities, were less likely to be involved in romantic relationships.”

Natalia Hemley, a 2015 Columbia journalism alumna, experienced a different form of this discrimination: Men who were attracted to her had problems of accepting her use of a wheelchair because her looks defied certain stereotypes.

“People don’t believe that I actually need to use my chair,” Hemley said. “They’re like, ‘Oh, you look so normal,’ because I’m a cute, blonde girl using a chair … I will go out with my friends to a club and a guy will have hit on me and said, ‘Oh, that chair is just a prop, right? You don’t actually use that because you don’t look like you belong in one.’ I never understood what that means.”

For fashion and beauty ideals to change, Hemley said brands must feature all walks of life by showing that people who use a wheelchair are beautiful too.

To break these social misconceptions and barriers, Crawford and Ginny Dixon, a photographer who has been part of two Pulitzer Prize-winning staffs at the Los Angeles Times, created The Raw Beauty Project to broaden perceptions of beauty.

The project showcases photos of women living with various disabilities, capturing their beauty, power and passion. The exhibit debuted in 2014 at ACA Galleries in New York City and has been featured in popular publications such as O, The Oprah Magazine and the Huffington Post.

These measures taken to provide women with disabilities a platform to speak and let themselves be seen are only the first steps in the culture of seeing disabled bodies as mistakes because they are different from what is traditionally seen as “normal.”

“Disabled people are taught to hate their bodies in a way that ‘we’ll never change,’ so that is the most unhealthy part of it,” Marcos said. “I never hated being disabled and that was what alienated me so much from the disabled community.”

Marcos said the vlog makes her feel empowered because she gets to share her ideas of beauty, perception and representation to others.

“Disability is not just an illness; it’s an identity,” Marcos said. “Starting the vlog was this reconciliation [of] ‘This is what I look like, this is who I am, and now I am comfortable with it,’ and I want other people to be comfortable with themselves as they are.”

SIDEBAR: FASHION ACKNOWLEDGES PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

Open Style Lab—a nonprofit that designs stylish clothing for people of all abilities—started at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and was founded after the 2013 Boston Marathon Bombing to help victims of the attack, many of whom were left with disabilities.

The lab became a class in fall 2016 at Parsons School of Design, during which occupational therapists and students created functional and fashionable designs for people with disabilities, according to Christina Mallon, an Open Style Lab board member who has been paralyzed in both arms for seven years.

In the class, students are paired with clients who have disabilities and design garment prototypes that can better assist the clients’ needs, Mallon said. The prototypes are then presented to an audience of fashion editors and product designers, she added.

A group of students in a 2016 Parsons case study created the SUITable, an adaptive and adjustable sport coat equipped with magnetic closures for individuals with limited dexterity.

“[The audience is] really surprised that something doesn’t exist for their need,” Mallon said. “These students have taken the time to take this class because they want to include [people with disabilities] and I think [audience members] are really excited to see these students putting [people with disabilities] first.”