Educating ‘the other’ at Columbia

May 12, 2014

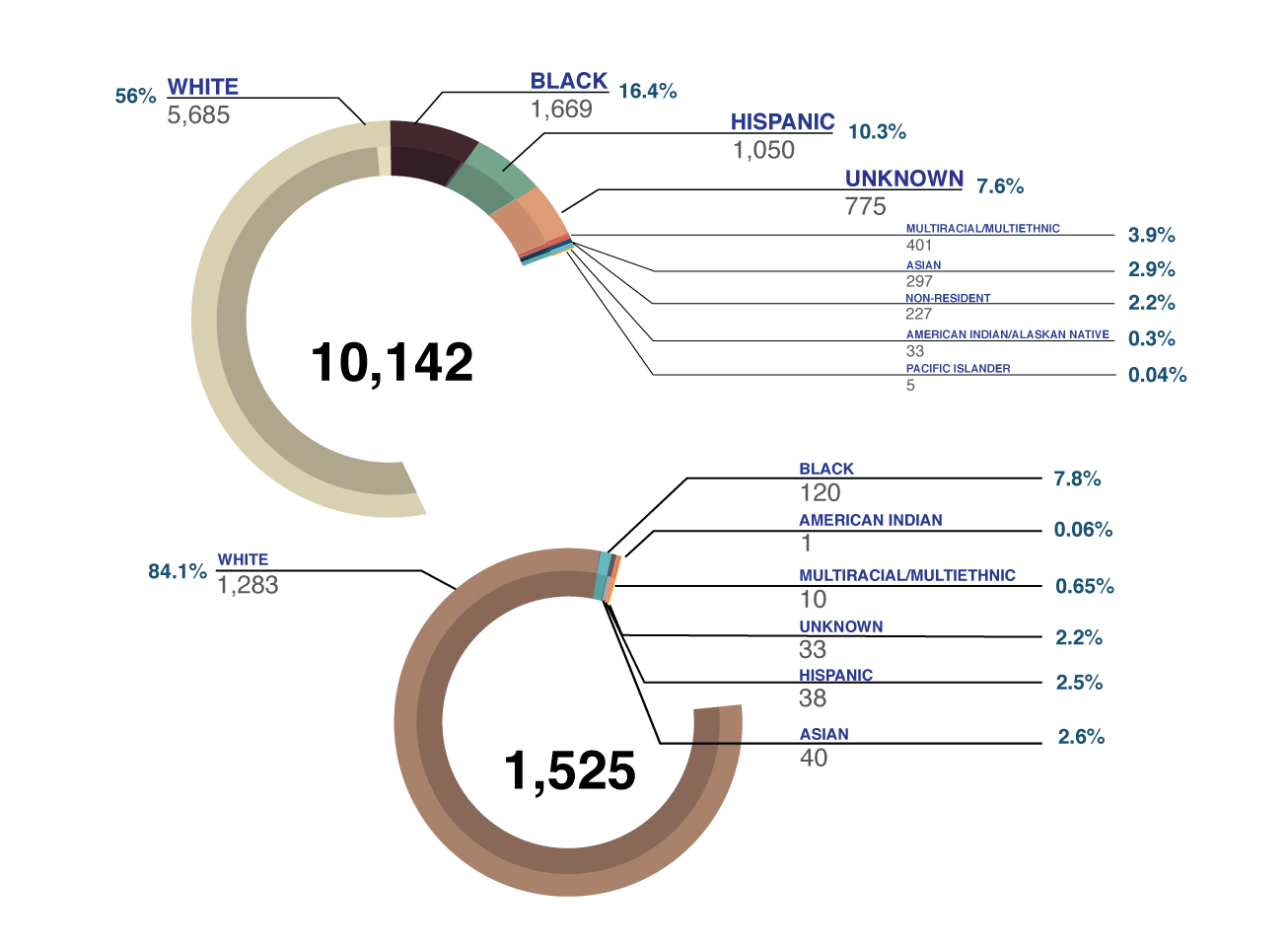

Diversity Statistics

Marcus Martin, former president of the Black Film Society and senior Cinema Art + Science major, spoke in a student-produced documentary to express his frustration with Columbia’s lack of diversity in its faculty. The Black Film Society, a student organization that hosts critical discussions about films, produced “Black Sheep,” a documentary featuring students and faculty talking about the lack of female and minority representation in the Cinema Art + Science Department’s faculty and curriculum, which Martin and others were frustrated with.

“A lot of the faculty [are] limited in their understanding of black art in the sense of black story,” Martin said in the film. “And because of their foreignness to it, they don’t know how to critique it. They don’t know how to give us what we need and yet we’re paying the same amount of money as the next person.”

The lack of diversity in faculty and staff is not limited to one department. Although Columbia brands itself as the largest and most diverse private nonprofit arts and media college in the nation, the college’s faculty demographics have not kept up with the growing heterogeneity of its

students. Race, ethnicity and gender are not inhibitors of an instructor’s teaching abilities, but Columbia’s lack of faculty diversity can cause some students, like Martin, to feel disconnected from teachers and curricula.

As of fall 2013, 82 percent of Columbia’s full-time faculty and 85 percent of its part-time faculty identify as white non-Hispanic, according to statistics from the Office of Institutional Effectiveness. In terms of gender, the college is doing better. Approximately 53 percent of Columbia’s full- and part-time faculty are men, and the other 47 percent are women.

However, about 34.1 percent of Columbia students identify as an ethnic minority, according to Royal Dawson, assistant vice president of the Office of Institutional Effectiveness, while approximately 79 percent of full-time faculty at higher education institutions identified as white, according to 2011 National Center for Education Statistics. The center did not have figures for adjunct faculty members.

The college’s statistics break ethnicity into categories such as African-American, Hispanic, Asian and Pacific Islander. However, Columbia does not have a separate category for faculty of Middle Eastern descent because the college must categorize ethnicity based on federal guidelines, according to Dawson.

While Columbia has a disparity in numbers of minority faculty members and students, it is not alone. According to an article published in the December 2013 issue of the Journal of Higher Education, 47.1 percent of full-and part-time faculty employed at two- or four-year universities are women and only 18 percent identify as a racial or ethnic minority, putting Columbia in line with the national average.

With four out of five full-time faculty members listed as Caucasian, cultural differences between faculty and students can affect students’ experiences at Columbia.

When Linda Garcia Merchant, a former adjunct professor in the Business & Entrepreneurship Department at Columbia, was admitted into the college’s Master’s of Fine Arts program, she expressed an interest in making films for Latino and Spanish-speaking audiences, adding that she wanted to pursue a master’s degree so she could teach. Merchant said the department did not have a Latino professor to provide feedback on her film, prompting her to seek help from Latino film teachers at other colleges. Merchant did not anticipate that Columbia professors would try to alter her work or that she would eventually be asked to leave before completing her degree.

Merchant said her professor asked her to almost completely restructure “The Benjamin of The House,” a film chronicling the family drama of a protagonist named Benny whose name is based on the ill-fated biblical Benjamin. Her professors asked her to change various aspects of the film, ranging from the name of her characters to translating the entire script from Spanish to English.

“If you can’t try things out in graduate school, where can you try them out?” Garcia said. “The coursework is fine. The structures are fine. It’s when you get to the art that there’s a problem. It was always about ‘appealing to this broader audience.’”

Michael Caplan, associate professor in the Cinema Art + Science Department and one of Merchant’s professors, said he recalls asking Merchant to translate her script to English so he and the other students in the class could understand it. However, he said he does not recall asking her to change the characters in her film.

Although some students would like a more diverse faculty and staff, legal barriers meant to promote diversity may be stifling it. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 strictly prohibits employment prejudice based on several factors, including race, color, religion, sex and national origin. Given that such discrimination is outlawed, the college cannot—and does not want to—hire faculty based on their race, according to President Kwang-Wu Kim.

In the future, Kim said he wants to appoint an administrative member to oversee diversity across the college and hire faculty with various perspectives, adding that hiring people based on their ethnicity would not fully address Columbia’s problem with faculty diversity. In higher education, diversity is usually used as a term to address race, Kim said, but the conversation needs to include other factors such as political beliefs and socioeconomic backgrounds.

“The problem with the conversation about diversity is that it’s just about people looking different [and] that it can stop there,” Kim said. “Diversity in higher education has become sort of a code word for quota. So I would rather talk about something like a commitment to ‘the other.’”

Other local colleges and universities have administrators who monitor diversity. In addition to having various offices for students of different cultures, the University of Chicago assembled the Diversity Leadership Council, a group of administrators who oversee the diversity of its staff, according to William McDade, deputy provost of the University of Chicago and co-chair of the Diversity Leadership Council.

There is a small number of qualified applicants of color because many graduates of color do not continue into graduate degree programs and go into academia, McDade said. Approximately 43 percent of the university’s student body identifies as white, according to University of Chicago statistics. The university’s human resources and registrar offices could not be reached for comment regarding faculty diversity statistics.

“We want to try to have a diverse workforce [and] we want [University of Chicago] to be place where welcoming and engaging,” McDade said. “We want people to be able to understand that people of all cultures need to be involved in making it as excellent as it can be.”

While Columbia does not have an official office dedicated to overseeing diversity, the college has offices designated to assist students of different backgrounds and guide the instructors who teach them.

For example, the Office of Multicultural Affairs, a division of the Office of Student Affairs devoted to fostering communities and providing support for students of different backgrounds, has specialized departments for different groups of students such as the LGBTQ Office of Culture & Community, International Student Affairs and Asian Cultural Affairs.

The Center for Innovation and Teaching Excellence, a center that organizes programs on various subjects to improve faculty instruction, has programs addressing how to instruct students of different backgrounds. The center organizes programs on topics such as digital media, diversity, and inclusion. Soo La Kim, the director of CITE and a “First Year Seminar” instructor, said the workshops usually attract 15–30 different attendees per session, so CITE works directly with Multicultural Affairs to host luncheons and discuss issues of diversity with a broader audience.

“One of the limitations to what we do is we can’t force people to attend our workshops, so often people who attend are already interested in teaching and learning in these ways,” La Kim said. “There has to be that willingness to learn and grow in your teaching.”

Lott Hill, executive director of CITE, said the center hosts luncheons with Multicultural Affairs regarding diversity and inclusion and offers free materials on the subject. CITE provides financial compensation for faculty who attend the workshops and sends letters of recognition to department chairs who participate in the program.

Fo Wilson, an associate professor in the Art + Design Department, said it is important that students see themselves represented in the curriculum so they feel connected to their coursework. Wilson said it is unfair for students of color or different backgrounds to have to seek equal treatment while completing their coursework.

“They have to do the job to create an atmosphere where they get the kind of teaching and learning that they wanted,” Wilson said of the students involved in the “Black Sheep” documentary. “They’re trying to get their teachers to teach them properly, and that should not happen. That’s not fair.”

In a study published in the June 2010 issue of the College Student Journal, researchers examined perceptions of and satisfaction with diversity in individual departments. After distributing electronic surveys to students at a predominantly white school, researchers found that minority students were less satisfied with the existing degree of faculty diversity and saw a greater need to increase it. The minority students also agreed that increased faculty diversity would contribute to their educational experience.

Greg Owens, a junior arts management major, said people of color have been represented in his coursework and served as guest speakers, adding that he feels more connected to the course materials related to black culture.

Owens said he thinks diversifying the curriculum would make students feel more connected to their coursework. He said the black perspectives and topics are not as deeply discussed during some of his general education courses, and he has been the only black male in some of his courses. As a result of lack of diversity in“Writing and Rhetoric” and “Oral Expressions” courses, Owens said he felt pressure to not stand out.

“I think [diverse faculty] would help, but the curriculum itself needs to be diverse,” Owens said. “In the back of my mind, I feel like I do have to work hard because I stand out.”

Jennie Fauls, assistant director of Composition in the English Department, said the first-year writing program instructors are aware students of different backgrounds may have received varying qualities of English education. Fauls said course materials in the program include books and updated anthologies that reflect societal changes such as “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks,” the Rebecca Skloot book chronicling the life of a poor tobacco farmer whose cells were taken for various medical uses.

“If a student was only exposed to one kind of author or media or subject, we’d be robbing them of the opportunity to deal with the real world,” Fauls said. “You cannot avoid the subject of diversity in a college education. It’s a pathway to talking about difference and identity, and that’s what students are here to discover about themselves.”

Jasmine Brown, a sophomore radio major, said she has not had a speaker of color come to her class, and she notices a lack of racial diversity in her courses. Though there appears to be lack of racial diversity, Brown said she is treated the same as other students in her classes.

Brown said despite radio traditionally being a white, male-dominated field, she has had some female speakers visit her classes, adding that students can still gain knowledge at Columbia even though they had a bad experience.

“Everybody brings something different to the discussion,” Brown said. “Just because they didn’t have the experience that I had … doesn’t take away from the fact that I’m being educated.”

Although some students have the opportunity to continue learning at Columbia, Merchant’s time at Columbia ended after a year. In a letter explaining her departure, the college said Merchant already had significant experience as a filmmaker, adding that she challenged her professors, did not understand how to structure a story and refused to learn.

Despite the difficulty in leaving the master’s program, Merchant said she did not criticize the department and she learned a lot about filmmaking.

“What was more difficult for me was that I didn’t get a chance to redeem myself or prove myself,” Merchant said. “And the entire time while I was presenting [The Benjamin of The House] at screenings or panels, I never had a critical word to say about this place.”

Jesus Iniguez, a junior art + design major, has had two Latino instructors at Columbia. He said his Latino professors made the coursework more engaging and understanding because they share a cultural background. Having more women professors would also help students connect to the material, Iniguez said, adding that age difference between professors and students can contribute to cultural disconnect. As one of few Latino students in courses, Iniguez said he feels pressure to make his work the best it can be.

“[Diversity] is basically Columbia’s slogan, but the student body is not that diverse and neither are the faculty,” Iniguez said. “[Latino students] are so scarce, but we make up a majority of this city. I want to represent all of them because you’ll only see a couple of them.”