Sounds like independence

Andrea Cannon SENIOR GRAPHICS EDITOR

Sounds like independence

February 16, 2015

In 2011, alternative-rock band The Maine was working on recording its third album, Pioneer, in a studio. According to guitarist Kennedy Brock, the album was recorded and presented as a final product to Warner Bros. Records in hopes of developing a partnership to help the band release the album. But Warner Bros. refused to stand behind the album unless the label could have an influence on the creative direction of it, Brock said in an email.

“At the same time, we felt that we could not compromise [with Warner Bros.] while also upholding the integrity within our music,” Brock said in the email. “[Warner Bros.] didn’t want to put out the record as it was, and we refused to put out anything but. We spent a long while in this stalemate before [Pioneer was] released, but it was the only way to get the music we loved out in the open.”

The Maine independently released Pioneer on Dec. 6, 2011, selling more than 12,000 copies in the first week and debuting at No. 90 on the Billboard Top 200 chart. The Maine independently released its fourth studio album, Forever Halloween, two years later in June 2013 with help from the 8123 Artists’ Collective.

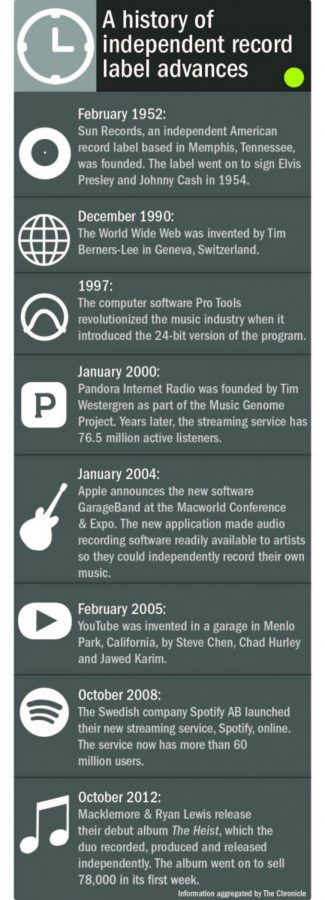

Three major music groups—Warner Bros., Sony and Universal—own countless record labels in the industry and financially support all of an artists’ recording and touring efforts as well as their marketing campaigns. But are they really necessary when musicians can self-produce music easily with the help of audio recording applications like GarageBand, Logic and Pro Tools and release their work through web platforms such as YouTube, SoundCloud and Bandcamp?

The abundance of opportunities to self-produce and promote can energize some and intimidate others. Anyone with GarageBand and an Internet connection can publish their music, said Casey Rae, CEO of the Future of Music Coalition, which is good for releasing art into the world but also makes it harder to be heard.

“Artists are now in a position of instead of having only one way of entering the marketplace, they have a lot of choices and sometimes those choices can make you feel overwhelmed or paralyzed,” Rae said. “[Record labels] act as a filter. When I think of our partners in the independent label sector, I’m always impressed with their continued ability to bring forward really great art.”

The independent label and recording sectors of the music industry are going to continue to be a “force to be reckoned with” in the industry’s growing economy, Rae said.

Most artists still want to go with a label, although it may not be one of the big three. According to a study conducted by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry in November 2014, seven in 10 unsigned artists have said they wanted a record deal with a label to defer recording and touring costs, in addition to receiving an advance payment prior to the record’s release.

Brock agrees that artists face disadvantages when deciding to release music independently. Independent artists do not have the same safety net when they decide to go out on a limb, but Brock said in an email that it works for The Maine and the vision the band has for its career.

“When we attempt to do something risky, that risk falls on us and not somebody else,” Brock said in the email. “We rely on a much smaller team to get similar hurdles leaped. That can be an issue—not having enough hands when we are juggling so many things. Having the core team we do—that works harder than most–—really allows us to overcome that disadvantage.”

Charlie Phillips, head of legal and commercial affairs for Worldwide Independent Network, a London-based organization designed to represent the independent music community in 30 countries, said self-recording and releasing music will continue to be popular among artists, but it is not necessarily a smart monetary choice in an environment that remains controlled by major labels.

“Sadly, we have a lot of challenges on our hands to be able to make [recording and releasing music independently] easier and much more viable to make it economically worthwhile,” Phillips said. “The way the digital market is set up still plays into the hands of the huge tech companies. The entire recorded [music] industry still doesn’t have an answer as to how we can properly value the hard work that all of us are doing—major and independent labels or self-releasing.”

Cara Duckworth, a spokeswoman for the Recording Industry Association of America, was upbeat about the ability of the industry to meet this challenge and generate income from streaming.

The recording industry is now a 70 percent digital industry, meaning that record labels are acquiring revenue from paid versions of new and distinct streaming services like Spotify, Rdio and Rhapsody, Duckworth said. The industry’s ability to adapt very quickly gives weight to its role as a sector of the technology industry, too, Duckworth said.

“If we’re looking at the trends today, I think streaming has come a long way in helping industry revenues,” Duckworth said. “A big portion of our revenues are coming from streaming services, including paid subscriptions for services like Spotify and Rhapsody. Those revenues are increasingly adding value not just to record labels, but to everyone within the music ecosystem.”

The RIAA and the organization’s retail partner, Music Biz, created WhyMusicMatters.com, a website designed to introduce music consumers to the thousands of new and distinct authorized streaming services online and help them find the right fit for their listening preferences, Duckworth said.

“We’ve tried to make [WhyMusicMatters] a site that people can keep coming back to learn more information about all of the different services out there and about the music industry,” Duckworth said. “If you’re interested in streaming and you’re not really sure if streaming would be a good fit for you, then you can go [to WhyMusicMatters] and look into the different streaming services.”

The larger players in the industry are taking a leadership role in making various streaming services work for musicians, Duckworth suggested, noting that “Major labels have worked proactively with various streaming services to give compelling, innovative options [for listening] that fans love.”

While the financial savvy of the majors is undeniable, do they offer advantages in helping artists realize their vision? Phillips says no.

“[If you’re signed to an independent label,] you will retain a considerable amount of artistic control,” Phillips said. “You will not be treated as a widget or a commodity. There is an element of more long-termism around the relationships that we see between the independent labels and the artists that are signed to them. There’s a closer relationship between the art and the business.”

With the emphasis changing throughout the last 15 years from radio airplay and CD sales to distribution via the Internet and social media, independent labels have become more visible and respected in the industry, said Richard Bengloff president of the American Association of Independent Music. Everybody now has access to the music industry, but that is a good and bad thing because it makes it much harder than it used to be for musicians to be discovered, Bengloff said.

“Per Billboard in 2005, the major labels were over 75 percent of the music industry in terms of copyright ownerships and

revenues,” Bengloff said. “Now, [major labels are] down to 65 percent, so the independent [labels] have grown from 25 percent to 35.1 percent.”

Another bone of contention is whether labels offer advantages in communicating an artist’s message through social media. Sites such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram have played a crucial role in the development of artists’ careers. NextBigSound.com uses data collected about more than a million artists, their album sales and social media usage, to look at the state of the music industry. Liv Buli, resident data journalist for Next Big Sound, said social media brings a new meaning to how fans expect artists to interact with them online.

“There’s an expectation for how artists are able to reach you and engage you,” Buli said. “Artists used to be a lot more isolated. It was much easier to have a record label create an image for you and you would go in the studio and go on tour and that was all the exposure you had. Now, your fans expect to be able to reach you through the Internet. That causes artists to have to learn a whole new set of skills and then kind of changes the relationship between artists and fans.”

Bengloff agrees that it is much harder to get noticed in today’s industry because of all the noise created online from an overload of aspiring musicians, but he said he thinks that artists who are represented by labels have a distinct advantage.

“[Because of the Internet] we have all this extra access, but people still need a label because everyone has access,” Bengloff said. “You want someone who’s a trusted source, so when you’re calling the press or you’re looking to get an agent for your touring or just knowing the best way to work the system is really important.”

According to the study conducted by IFPI in November 2014, doubts about the future of record labels are unsupported.

“While the digital music marketplace has been transformed by the growth of new services, artists still turn to record companies to help them cut through the almost infinite amount of music available to reach a mass audience,” the study stated. “Record companies remain able to reinvest the profits generated by successful campaigns in the next generation of artistic talent.”

Phillips said there will always be a role for labels—major or independent—because artists need those economic partners to succeed.

“[Record labels] will look very different in years to come,” Phillips said. “A label is a label. It’s called a particular word, but what that means is an administrative and economic business relationship partner. There will always be a need for them.”

Even though the role of a record label will change drastically as the industry continues to grow, Phillips said he sees independent labels playing a major role in the development of the music business. Most major record labels are only in the industry of recorded music, whereas many independent labels are handling recorded music, but also handling their own management and publishing companies, Phillips said.

“[Independent record companies] have been branching out to different areas of the industry,” Phillips said. “Whilst the overall value of recorded music may be put under some pressure, most of these companies are not solely in the industry of recorded music. If you’re only working in recorded music [and] recorded music takes a dive, then you take a dive. But if recorded music is only an overall part of your operation, then you might only take a hit on that side of your business.”

Many independent companies have pulled through some of the industry’s rough storms throughout the last few years precisely because they recognized it would be more practical to be responsible for the recording, managing and publishing, making these companies more resilient than their competitors, Phillips said.

The structure of a career in the music industry is highly dependent on the artist and the direction they wish to go, Brock said. A more structured plan—such as having a big team of managers and promoters cover the business side of the artists’ career and a label cover the costs of recording their albums and touring—works for some artists, and for them, major labels are more effective. But for artists like The Maine, who have a vision and want things to be done in a particular way, the independent route is better, Brock said in the email.

“Artists nowadays have such an advantage over the old major label scenario,” Brock said in the email. “The ability to get your music out to people is easier than ever before if you’re willing to work hard. Because nobody will do it for you and everything is done by your own two hands.”