Lead-contaminated water found citywide, what’s next?

Lead-contaminated water found citywide, what’s next?

April 23, 2018

A finding of high levels of lead in Chicago tap water, reported in an investigative study by the Chicago Tribune on April 13, has alarmed residents and led city officials to propose solutions to what is emerging as a serious and costly public health problem.

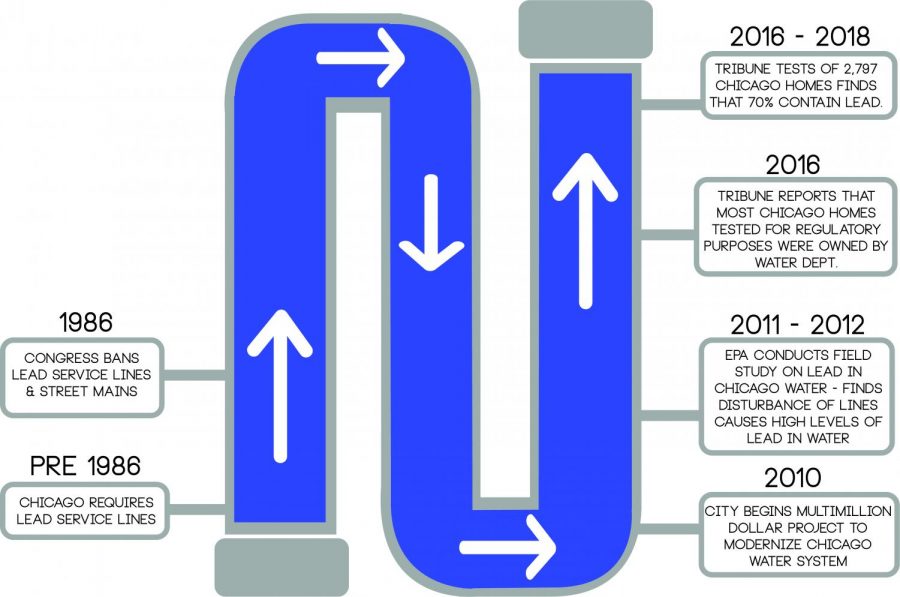

Of nearly 3,000 homes tested by the city during the last two years, nearly 70 percent were found to have lead in their water. Thirty percent of tap water sampled had lead concentrations above 5 parts per billion, the maximum allowed in bottled water by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

An aggressive campaign by Chicago to replace water mains, beginning in 2010 dislodged lead in homeowners’ pipes, resulting in contaminated water. Lead pipes were banned by Congress in new construction in 1986 but were required by the city of Chicago up until that time, according to the Chicago Tribune.

At City Council’s April 18 meeting, several aldermen introduced a resolution to hold hearings on violations of the Safe Water Drinking Act, the Clean Water Act and protocols for lead testing, to be overseen by the Rules and Ethics Committee, according to Chicago City Clerk records.

“We want to make sure this issue is not kept on the back burner,” said Liliana Escarpita, director of Communications and Policy for Ald. George Cardenas (12th Ward), chairman of City Council’s Health and Environmental Protection Committee. “We want to make sure we don’t have a Flint, Michigan, situation on our hands. We want to get as much data as we can.”

However, while the Tribune tested Chicago’s tap water to check compliance with FDA standards for bottled water of 5 parts of lead per billion, the city is held to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency lead and copper rule, which is 15 ppb, according to the EPA website.

Chicago also releases annual water quality reports, available on the city’s website.

“Chicago’s water consistently meets and exceeds the U.S. EPA’s standards for clean, high-quality drinking water,” Megan Vidis, a spokeswoman for the Chicago Department of Water Management, said in an April 19 email statement. “The Department of Water Management proactively uses corrosion control measures to ensure that it stays that way.”

Any Chicago resident concerned about lead levels can call 311 to have their water tested, Vidis said.

No level of lead is healthy, and exposure in early childhood is associated with poor achievement on standardized reading and math tests. Preventing lead exposure is critical to improving school performance, according to a April 2015 Environmental Health Journal report.

Lead exposure in young children can disrupt brain development and negatively affect behavior and attention spans, said Helen Binns, a pediatrics professor at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine.

Even small amounts of lead exposure can increase an individual’s blood pressure, which could damage cardiovascular health. Lead is especially harmful for pregnant women, Binns added.

“What’s ironic to me is that we were the last city to require the use of lead service lines up until they were banned in Chicago in 1986, but literally up until that day they were still putting them in,” said James Montgomery, an associate professor of Environmental Science at DePaul University. “Why can’t they foot the bill to remove the lines? The bottom line is that would be costly.”

Montgomery questioned how Chicago can replace and pay for new service lines when 85 percent of homes in the city have lead pipes. According to a 2016 American Water Works Association survey, there are still 6 million lead pipes in service in the U.S. Some cities have raised water rates to cover the expense, while others do a cost-share program, Montgomery said.

“The city has to take responsibility for it, but I am not necessarily saying that they have to be the ones to pay for it,” Montgomery said. “But it is an environmental justice issue that is going to affect low-income people who are renters in units that are not owner-occupied with landlords who may not care or have the means to pay for replacing the water pipes.”

Under the city’s plumbing code, individual property owners are responsible for maintaining service lines.

It is expensive to replace lead pipes and that cost will probably be passed on to renters, Montgomery said. This could be detrimental to low-income households and college students who are typically on tight budgets, he added.

Chicago’s South and West sides have the highest concentrations of lead poisoning among children, which are typically low-income households and people of color, Montgomery said. Using certified water filters for drinking water is a preventive measure, he added.

In lieu of replacing lead service lines, which is a costly process, there are independently certified drinking products that range in pricing and complexity, such as simple pitchers that use multistage reverse osmosis solutions and whole-house installations, said Eric Yeggy, director of Technical Affairs for the Water Quality Association—a Lisle, Illinois-based water treatment industry association. These are the safest methods individuals can take to ensure they are not being exposed to lead in their tap water, he added.

“The ultimate solution is to replace the lead pipes, but it is expensive to remove all those service lines,” Yeggy said. “And that construction activity, including repair and replacement of the service lines, can disturb sediments that have built up in the pipes and the plumbing, and some of those sediments have high amounts of lead.”

Removing the lead pipes should be a shared responsibility between property owners and the city, said Joseph Fong, president of the Association of Condominium, Townhouse and Homeowners Associations.

“There needs to be pressure put on City Council to get it done [and] put priority on replacing the lead pipes,” Fong said.