When PLUR goes wrong: Harm reduction groups try to keep music festival fans safe from laced drugs

June 22, 2022

Sparkly pashminas, pinecone necklaces, LED hula hoops, tie-dye and neon clothing — the kooky outfits and light toys are only a fraction of the fun that goes on at an electronic music festival. Friends dysfunctionally stumble around grass fields with arms linked, laughing and exchanging beaded bracelets, called kandi, with strangers.

The exchange of kandi symbolizes a popular mantra in the electronic dance music (EDM) community, PLUR: peace, love, unity and respect.

If you look around with an intent (and sober) eye, you’ll notice how euphoric everyone seems to be while dancing to the dubstep of Liquid Stranger, funk of GRiZ and electro-soul of Flume.

But you’ll notice some oddities too: wide eyes and dilated pupils, jaw clenching and teeth grinding — even some people being carried out of the crowd before the headliner starts — legs limp, hair disheveled, glittery makeup smudged.

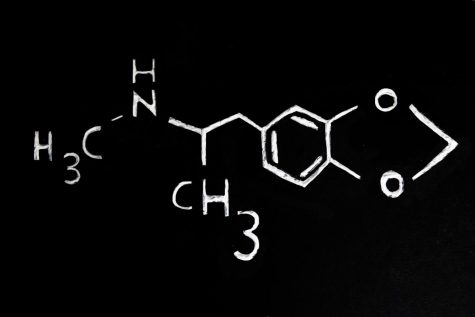

Music festivals tend to be a breeding ground for young adults to try drugs for the first time. Molly, slang for MDMA, is a popular synthetic drug chemically similar to stimulants and hallucinogens and provides feelings of pleasure, emotional warmth, distorted sensory and time perception for three to six hours. It most commonly comes in the form of a pressed pill or capsule, with a single dosage ranging from 70mg to 100mg, costing $15 to $25.

Mitchell Gomez, now 40 and the executive director of DanceSafe, a health education and harm reduction nonprofit, remembers going to his first rave a few days after his 14th birthday and searching for LSD. He was far more interested in trying psychedelics, but he settled for MDMA since it was easier to find.

Although in elementary school you’re taught D.A.R.E., children don’t stay young forever; they become curious young adults. Substance use in music scenes is not new; just ask your grandparents about the ‘60s and its hippies, psychedelics and Pink Floyd.

However, these days, drugs are heavily impacting a different genre, and the stakes are higher than ever. Fentanyl lacing and drug misrepresentation have become increasingly more common in party drugs like cocaine, ketamine and MDMA, which are widely popular in the electronic music scene. To combat this, harm reduction groups attend music festivals, test people’s drugs and educate event-goers on safe use.

“I’ve had more than one email a day come in about the subject where [the person says], ‘Hey, my friend died, and the toxicology report showed fentanyl, and how the hell was there fentanyl in this cocaine?’” Gomez says.

Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50 times more potent than heroin, is the most common drug involved in overdose deaths. An amount visually equivalent to a few grains of sand has the potency to kill. Years ago, Gomez rarely received emails about people’s drugs containing fentanyl. Now, he says it’s a normal part of his job at DanceSafe.

Drug overdoses — already on the rise since the late ’90s — have skyrocketed. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that a record-breaking 100,000-plus Americans died from drug overdoses between May 2020 and April 2021, a 29% increase from the previous 12-month period. Overdose deaths from synthetic opioids, primarily fentanyl, also rose in that period.

Brenda Cornejo is an operating room registered nurse at AMITA Health St. Joseph Hospital Chicago, a house DJ and a moderator for the Facebook group EDM Chicago, which has 79,900 members. She’s been to all the big Chicago festivals – Spring Awakening, Lollapalooza, North Coast and Riot Fest, often attending with nursing peers and bringing drug testing kits. At the North Coast festival, Cornejo encountered a person having a seizure and got them medical help.

“He didn’t seem like he was drunk. It seemed like he was on some sort of depressant,” she says. “There are so many different types of experimental drugs that people take.”

Hospitals can become overwhelmed during events like Lollapalooza, due to people taking misrepresented substances, mixing them, drinking alcohol and being in the heat all day, Cornejo says.

For 23 years, DanceSafe has conducted on-site drug testing at music festivals, specifically within the electronic music scene, and helped educate people on safe drug use. The organization manufactures and sells testing kits, and its 1,000 registered volunteers hand out educational pamphlets at events nationwide.

“We could test 1,000 people’s drugs for the cost of what we spend hospitalizing one person who took a misrepresented substance,” Gomez says. “So even if you don’t care about the civil rights or drug arguments, this is just the cheaper option for the taxpayer.”

Cris Bleaux, 36, remembers seeing DanceSafe at a Halloween-themed rave in Wisconsin when he was 17. He purchased “rolls” (MDMA) from a dealer at the show and saw DanceSafe volunteers doing pill testing, so he tested his drugs, which were indeed MDMA.

Bleaux has now worked in harm reduction professionally for 12 years, in positions that include overdose prevention manager at Chicago Recovery Alliance and a member on the board of directors at Howard Brown Health.

“There are a lot of folks in the abstinence-only community that just don’t respect harm reduction as an avenue of safety,” Bleaux says.

In March 2021, President Joe Biden signed legislation that allocated an unprecedented $30 million for harm reduction services. Critics slammed the program, calling it a “handout promoting drug use.”

Gomez says that not providing safe supplies to drug users is identical to not giving high schoolers condoms to stop them from having sex.

“There’s no statistical decrease in the number of people having sex — there’s an increase in STIs and pregnancies,” he says.

If someone sees there’s no testing available, they aren’t going to say, “Oh, I guess I just won’t take the drugs now,” Gomez says. “Realistically, they’re just going to take them untested, which often results in further problems. People die from drug misrepresentation all the time.”

Steve Mientus, the director of events for Aramark-Navy Pier, says many festival production companies don’t want to be associated with drug testing, because it comes off as if they’re promoting drug use, when “that’s just simply not the case.”

There’s a list of people who can say no to the presence of a DanceSafe booth at a festival: promoters, law enforcement, liability attorneys and venue owners. As a result, DanceSafe is told “no” far more than it’s told “yes,” Gomez adds — or they just get ignored. Gomez said that last year DanceSafe reached out to North Coast in Chicago, but they heard nothing back.

“There’s always going to be somebody that looks at it [only] for its surface value, which is testing people’s drugs for free,” Mientus says.

Mientus is a former resident DJ at Sound-Bar, a nightclub in the River North neighborhood. He doesn’t frequent shows anymore unless he’s on the bill, but when he does, he brings two narcan nasal sprays with him, he says.

Narcan is the nasal spray form of naloxone, an FDA-approved medication designed to reverse opioid overdoses. In Illinois, there is a statewide standing order that allows pharmacists to provide naloxone without a direct prescription to individuals.

In the past, Mientus has purchased the sprays online out of his own pocket but says he’s only had to administer it to someone once at a Chicago venue.

In January, Chicago launched an initiative that made narcan accessible at 14 public libraries across the city to prevent opioid-related overdose deaths, with plans to expand to 27 Chicago Public Library branches later in 2022.

DanceSafe focuses mainly on the electronic music scene and its festivals, which means that by design, the organization is missing out on helping a vast majority of drug users who don’t attend music festivals.

“That alone sort of creates a very weird dynamic where, by definition, we are dealing with a more privileged community,” Gomez says. “Having that dynamic at play is not something that I’m in love with and something we actively try to deal with.”

Gomez is optimistic that the drug epidemic can be solved through a regulated drug market. He believes drug checking is not a thing we should have to do, because drugs like MDMA should come from a store: legally manufactured with a regulated dose and an information booklet.

“Every major social change looks impossible the day before it happens and inevitable the day after,” Gomez says, quoting Holocaust survivor Alicia Appleman-Jurman’s book, “Alicia: My Story.”

People rewrite history so flawlessly that they sometimes forget how controversial some issues once were, he adds, referencing interracial marriage and women’s voting rights.

“I’m really hopeful that the drug war is one of those things that in a few years, we’re going to look back and be like, ‘Of course this [a regulated drug market] was what had to happen,’” he says.

How to get involved

Organizations like DanceSafe, Students for Sensible Drug Policy, the Zendo Project and Harmonia are all working to help end the drug war in America. Anyone can sign up for training, get involved as a volunteer or support advocacy groups like the Drug Policy Alliance.

The Drug Policy Alliance (DPA) encourages contacting your senator or representative to urge Congress to support the decriminalization of drug use and possession and instead promote drug education and treatment.

“Handcuffs will not solve the overdose crisis,” the DPA says on their website. “Prohibition fuels the overdose crisis. It pushes drugs underground where they avoid regulation. Here, drugs become more potent and dangerous. By promoting ‘just say no’ rhetoric, prohibition stigmatizes individuals, discouraging them from finding the resources they need.”

What to do if someone is overdosing

This information is taken from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Minutes Matter.

1. Check for symptoms

Common symptoms of a drug overdose include being unresponsive or unconscious, gasping, snoring or not breathing at all, shallow or slow breathing, blue lips and fingertips and clammy skin.

2. Call 911

Mention your exact location and phone number in case the call drops, along with any details you have on what drugs or alcohol may be contributing to the overdose. Those who report overdoses in good faith are protected by Good Samaritan laws if there is any criminal activity involved.

3. Administer naloxone (narcan) if available

Naloxone will block opioid effects in the brain and reverse an overdose; it allows the person to remain conscious and breathing.

4. Stay with the person until emergency responders arrive

While you wait for first responders to arrive, you can move the person onto their side to prevent choking or perform chest compressions if they are not breathing or have no pulse.

You can read the entire 2022 issue of Echo, as well as previous issues, on our website.