The music was still thumping at the wedding reception when Gabriel ‘Gonzo’ Gonzalez stepped outside into the California night in May, trying to console their younger brother.

Daniel Gonzalez, an off-duty U.S. Army medic, had been drinking, crying, unraveling. Gonzo, a senior film and television student at Columbia, guided him out of the noise and toward the car for air and quiet. Daniel Gonzalez sank into the driver’s seat, still sobbing. Gonzo walked around to the passenger side.

They never saw their brother’s gun.

Daniel Gonzalez died on the way to the hospital from an apparent self-inflicted gunshot. He was 26.

In the weeks that followed, Gonzo, a U.S. veteran who served in the Navy, went back to Kansas City — carrying the weight of shock, grief and questions.

In a nation where immigration barriers often intersect with moments of profound personal loss, Gonzo’s story is one of anguish — shaped by both gun violence and the border.

“I don’t know this feeling that I have,” Gonzo said. “Now, after losing a sibling — Billy Bob Thornton put it best — I’m fifty percent happy and fifty percent sad at any given moment, and it’s just a feeling that’s never gonna go away.”

Daniel Gonzalez was buried with military honors on June 5 at Leavenworth National Cemetery, Kansas, where he had been stationed for five years. He is survived by his wife, Lisandra Garcia.

Bryen Freigo, director of Combined Arms Center Public Affairs, said Daniel Gonzalez was off-duty at the time of his death. He declined to comment further because the death is still under investigation.

At the funeral, everyone was crying, family members, fellow soldiers from his unit.

“My sister’s kids were all crying,” Gonzo said. Daniel Gonzalez was their favorite uncle.

Their father, Carlos Gonzalez, wasn’t there. A Mexican national without U.S. citizenship, he was denied entry into the country despite urgent legal appeals and backing from nonprofit organizations and U.S. lawmakers.

Because he had entered the country illegally on multiple occasions, he can’t apply for permission to enter the country again until after March 2034.

“There are obstacles that you just don’t expect,” Carlos Gonzalez told the Chronicle in a phone interview in Spanish.

Even under previous administrations, deported individuals faced daunting challenges simply trying to return. But since Trump launched his second-term deportation campaign — marked by aggressive ICE workplace raids, record-high targets of thousands of arrests per day and use of wartime tools like the Alien Enemies Act—returning has become nearly impossible.

As of early 2025, ICE has carried out sweeping operations in sanctuary cities, deporting tens of thousands, including lawful residents and even U.S. citizens. Courts have intervened at times, such as blocking flights to third-world countries.

For someone like Carlos Gonzalez, the chance of reuniting with family in the United States, much less to attend the funeral of a U.S. veteran son, has all but vanished.

The family sought legal help from multiple sources, including the non-profit Binational Institute of Human Development and Councilman Johnathan Duncan and U.S. Rep. Emanuel Cleaver, both from the Kansas City area.

Duncan, a Latino combat veteran, expressed frustration in the case.

“This is the result of cruel policies by the Trump administration,” he said. “As a veteran who has seen the destruction and dismantling of federal agencies like the Veterans Administration, it doesn’t appear to me that President Trump or this administration cares about veterans, and I think you see this with the Gonzalez family.”

A friend was able to live stream the service to their father, who also wrote a letter for his son, citing Psalm 23 in the Bible.

The letter is buried with Daniel Gonzalez, tucked into his coat pocket.

Growing up in Kansas City

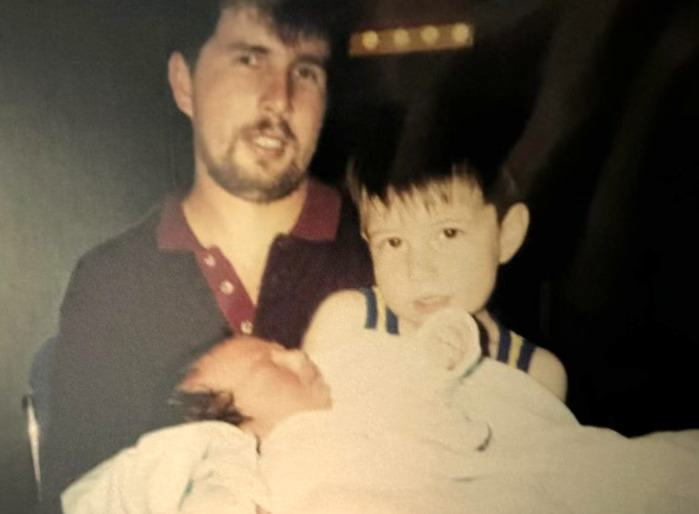

From their father’s marriage to their mother, Gonzo is one of five children and was born in Storm Lake, Iowa, in 1995. The family moved to the Kansas City area when they were eight, and Gonzo recounted a strong connection with their siblings.

Their parents split up around 2006, and shortly after, a custody battle ensued. Their father was still in their life at that time, but Gonzo would go months without seeing their brothers until visitations were set up.

Eventually, the dispute was resolved.

“I remember Daniel,” Gonzo said, recounting their reunion. “He was the first one through my mom’s door, and I gave him a big hug.”

But during their junior year of high school, their mother was “getting back into religion,” Gonzo recalled. While at church one day, she kicked Gonzo and their brothers out of the service and told them to wait outside until it was over.

Gonzo called their father, and he came and picked them up.

“They’re not perfect,” they said. “If I had my dad around to do that and other things, that would have helped more. Instead, I just joined the military and figured it out on my own.”

Gonzo, who recently turned 30, served at Naval Air Station Oceana in Virginia for five years through COVID. They were stationed on the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower when it broke the record for most days at sea.

After getting out of the Navy in September 2021, they decided to pursue a college degree and eventually settled on film and television at Columbia after a brief stint in computer science at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. They eventually want to work on documentaries and focus on “authenticity” in their films.

“Everybody tries to define, ‘What is truth?’ Whenever it comes down to it with film, it’s always subjective,” they said. “For me, I’m just trying to show ‘what is,’ instead of having some deeper meaning.”

Life without their brother

Gonzo is able to stay connected to their brother by the activities they used to do together: playing PlayStation 1 games like “Metal Gear” and remembering the dry humor that he used to have. One of their brothers’ hobbies was working on cars, like the ‘97 Grand Cherokee he reupholstered.

“He told my brother Manuel that he loved working on cars because you can always bring them back,” Gonzo said. “He said you can’t do that with people.”

In light of everything that has happened, they believe that love for everyone is better than pointing fingers and blaming others, and that reflecting on these types of situations is how someone grows.

Instead of taking a darker route, Gonzo, who is returning to Columbia in the fall for their final year, has been able to take their experiences and turn them into good, helping those who are in the same situation as them.

According to Gonzo, another father who had a military son who died was also denied entry into the country recently, and through the work that Gonzo is doing, they can lay “down the groundwork for the next person.”

“It was through that that I found purpose,” Gonzo said. “I wasn’t angry about anything.”

If you or someone you know are in crisis, please call, text or chat with the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988 or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741. Columbia College provides resources through the Center for Wellbeing. Students also have 24/7 mental health care via TimelyCare, Columbia’s virtual medical and mental health platform.

Copy edited by Vanessa Orozco