‘This is the first time’: Rohingya-Americans in Chicago cast their ballots

October 28, 2020

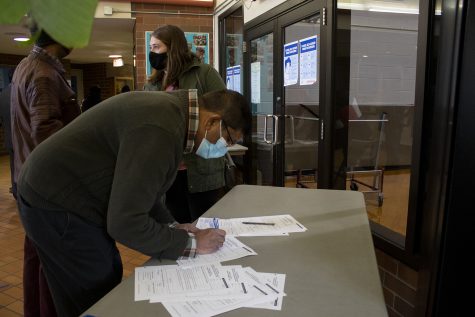

On a cool afternoon in late October, Abdul Jabbar packed his van with around 15 people and made his way to Warren Park. He was among other Rohingya-Americans and supporters on a mission to cast their votes in a U.S. presidential election for the first time.

For anyone, voting in a general election for the first time is a momentous occasion, but for Rohingya-Americans, voting in America brings a whole new sense of pride.

On Oct. 20, Jabbar wanted to share this moment with his community. Within a week of bringing the idea to both the program manager and education director at the Rohingya Cultural Center, 2740 W. Devon Ave., everyone at the center who was eligible to vote went to the polls together.

“Most of our Rohingya people, this is the first time we are voting,” Jabbar said. “Especially for myself, this is the first time I am voting in a general election. I was not allowed to vote in my hometown in my country because of my identity.”

Rohingya refugees began coming to Chicago in the early 2010s to escape persecution in their home country of Burma, now known as Myanmar, according to Sarah Pajeau, program manager at the Rohingya Cultural Center. Jabbar came to Chicago from Burma in 2012 and now works as a senior case manager at the cultural center.

Myanmar also has an upcoming election on Nov. 8, but the Rohingya people are not allowed to vote in it or any other elections because they are not considered citizens.

“The Rohingya minority Muslims are not allowed to become parliament members simply because of religion,” wrote the cultural center’s Executive Director Nasir Zakaria in an Oct. 20 press release. “The Rohingya are persecuted in Burma and stripped of our rights, such as education and freedom of religion. While we have proof of originating from Burma, we are not considered citizens. Due to the genocide, there are 1 million Rohingya refugees living in limbo in Bangladesh and other Rohingya refugees worldwide.”

Once Rohingya refugees come to America, they must have a Permanent Resident Card, also known as a Green Card, for at least five years and take a citizenship test to become a legal U.S. citizen.

The Rohingya Cultural Center offers citizenship and English as second language courses. Because the Rohingya language is only a spoken language and not written, Rohingya-Americans must take these courses to understand a portion of the citizenship test that requires the test taker to speak in English.

“Most of my adult students have never been in school,” said Susan Chestnut, the cultural center’s education director. “Most of the students that voted had been in my class for a year. I was always talking about voting and that it is one of the most important things you can do as a citizen.”

Chestnut said she put up information around the center on where to vote and its significance, but the push from Jabbar was what got more people interested.

“Had we just left it up to individuals, maybe not as many would have voted,” Chestnut said. “But having this be an event made it more special, and it showed the community members what they can get from going through the citizenship process. It’s hard to become a citizen … but it’s worth it in the end.”

Jabbar took the time to explain to his fellow community members the different parties and candidates running for office and left the rest up to them. He has offered to assist more people if they need it but does not recommend voting on Election Day because of the pandemic and the fear of overcrowding.

“It’s important to have a new government and also have new proceedings,” Jabbar said. “If we have a president who is willing to take more refugees and give us more opportunities to help our families get here, that would be very helpful. And we are hopeful that will happen.”