The ‘nucleus’ of R&B and soul: Brunswick Records made history in Columbia building

February 24, 2022

Jun Mhoon began working at Brunswick Records in 1973 as a staff drummer at age 19. At Brunswick, Mhoon laid tracks and demos for multiple R&B and soul artists, many of whom were from Chicago, including the Chi-Lites, Jackie Wilson, Gene Chandler and Tyrone Davis, among others.

Mhoon, a retired musician and record producer, Columbia music business alum and former faculty member in the music business program, said he hears hip-hop songs on the radio today that were lifted from tracks he played on years ago.

“That’s the power and the influence that music recorded at Brunswick, and most of it down on Record Row, has on young artists today,” Mhoon, 67, said.

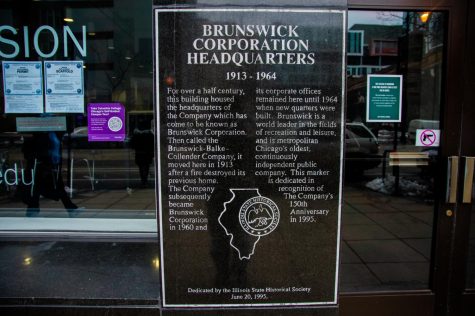

Brunswick Records’ history dates back to the early 20th century when the company first began in the record business inside of none other than Columbia’s 623 S. Wabash Ave. building.

Columbia’s archives show Brunswick Records resided in the building from 1913 to 1964, before moving to another location in the South Loop at 1449 S. Michigan Ave., where they stayed in an area known as Record Row until 1976.

The Brunswick-Balke-Collander Company, founded in 1845, originally made wooden entertainment installations including billiard tables, bowling alleys and bars, but the Prohibition shifted their business to records and recording equipment, birthing Brunswick Records in Chicago.

Mhoon grew up on the West and South sides of Chicago and got his start as a drummer for the Staple Singers at age 12 before working for Brunswick Records with producers Carl Davis and Nat Tarnopol. Mhoon described this time in Brunswick’s history as the “breeding ground” for soon-to-be famous R&B and soul musicians, alongside Motown.

“Chicago was the home. It was the basis of [music], and it was Record Row down on Michigan Avenue, well, that was the nucleus,” Mhoon said.

Despite their musical impact, Mhoon said the history of musicians in Chicago is not widely known, many coming from the South during the Great Migration in the 1920s.

“All that talent and that energy came from Chicago and came from these artists who, here they might have been born somewhere else, but they were nurtured and they were schooled in Chicago Rhythm and Blues,” Mhoon said.

Mhoon said the white recording labels used to refer to R&B as “race music” and refused to produce it, which prompted the launch of labels for Black artists like Vee-Jay Records, Chess Records and Brunswick Records.

“As we make music, our music reflects [the] economic situation, in many cases, education, the education that we have, and our environment,” said Fernando Jones, an adjunct faculty member in the Music Department and founding Blues Ensemble director. “And so, when you look at those three components, that’s why that music had the sound that it did without being apologetic.”

Jones said there was an opportunity for Black musicians in Chicago, but it still came with challenges, like a lack of access to sophisticated music equipment.

“You’re looking at music that was more than likely created by people who were first-generation Chicagoans, so their fans were from the South. And those fans were probably sharecroppers, so this was an opportunity to have a first shot at education, a first shot to be away from the whole Jim Crow situation but de facto segregation nonetheless,” Jones said.

Nathan Bakkum, senior associate provost and associate professor in the Music Department, said he has researched Brunswick Record’s role in music creation in Chicago, specifically during the ’60s and ’70s soul and R&B movement.

Bakkum said Brunswick Records was a pioneer in a music technology “explosion” in the late 1920s and beyond, fueling Chicago’s global music imprint.

“The number of legendary recordings from [the 1960s and ’70s] that were recorded, in part, produced, written along that stretch of Michigan Avenue, which I see as a sort of a south extension of the Columbia College campus, is just fascinating to me,” Bakkum said.

During the Fall 2021 semester, Bakkum said he led a walking tour of Record Row as part of the honors course “Big Chicago: Access, Civic Life and City Design” to teach students about the rich history.

Willie Henderson, a Chicago R&B musician, played on tracks at Brunswick Records like “Can I Change my Mind” by Tyrone Davis and recorded his own music there in the group Willie Henderson and the Soul Explosions. Henderson, a former faculty member in the Music Department, said working at Brunswick Records was never a dull moment.

“A lot of the things that we created back in those days is still being played now,” Henderson said. “You know, the hip-hop came basically from the music that we made. In fact, it’s so similar, other than some of the instrumentation is changed, but others basically telling the story in that group and all of that is still the same.”

Mhoon said while in his twenties, he wanted real-world knowledge from experts, and Columbia was the place for that.

As a student at Columbia in 1982, he founded AEMMP Records, the first student-run record label in the U.S. The label is celebrating its 40th anniversary this year.

Mhoon said he learned most from his students when he was a teacher at Columbia, helping mold the music business program into what it is now and teaching students about the history of music and the industry.

“The history is so important because young people now who are doing hip-hop, and even pop, don’t have the time or don’t necessarily know from whence they came, and they really did come,” Mhoon said.